[Click photos to view larger versions.]

The morning of April 9, 1947 dawned cool, breezy and decidedly gloomy across the Southern Plains. Thick fog descended like a blanket, reducing visibility to near zero in some locations. Patchy drizzle broke out from low, sullen clouds and fell as a fine mist over the expansive fields of sorghum and winter wheat. Farmers and ranchers rose before first light, thankful for every drop of rain that could be coaxed from the sky after several months of drought. The animals, like the weather, seemed to be unsettled. Cattle huddled together as if for protection from some unknown menace. Horses whimpered and fidgeted uneasily. Milk cows protested and balked at the prospect of their morning milking. To old timers, these behaviors seemed to portend a storm. Still, April was always a fickle month, bringing radiant warmth, biting cold and booming storms to the Southern Plains in seemingly equal measure. With temperatures struggling to reach 50 degrees and a dense stratus deck choking out the morning sun, the conditions hardly brought to mind the “tornado weather” that a lifetime of living in Tornado Alley had taught residents to fear and respect. However, unknown to the people below, the vast, chaotic machinery of the atmosphere had already set into motion a series of events that would culminate in perhaps the greatest storm in the region’s long and bitter history.

Eighteen-year-old Ramona Kolander rose at dawn on Wednesday, April 9, rubbing the sleep from her eyes as she dressed, ate her breakfast and helped ready her younger sister for school. As a senior at the local high school, the morning was part of a familiar routine that was about to change with the approach of graduation day. The wind had picked up since the previous night, sending ripples through the expansive fields of winter wheat that surrounded the farmhouse near the Texas border, southwest of Shattuck, Oklahoma. Shattuck was something of a throwback to the Old West, not dissimilar from the dozens of other small settlements that broke up the otherwise desolate landscape of the Southern High Plains. Woodward, the closest thing to a city that the region had to offer, lay 35 miles to the northeast. Growing from its initial founding during the great land run of September 16, 1893, the town of 5,500 boasted an airport, a paved Main Street, and the Elks Rodeo, one of the largest in the United States. After the hard, lean years of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, during which the town’s growth slowed to a crawl, Woodward was reinvigorated by the tremendous boom that gripped the country following the Allied victory in World War II.

Twelve miles southwest of Woodward, just south of the community of Fargo, 34-year-old Margaret Larason stepped out into the damp morning. There was plenty of farm work to do but, being seven months pregnant with her third child, she knew better than to put undue stress on the baby. Her husband, Bert, was away in Oklahoma City, where he served in the Oklahoma House of Representatives. Retrieving the morning newspaper, Margaret scanned over the headlines. There was certainly no shortage of newsworthy stories. The celebrated industrialist Henry Ford had died just two days earlier after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage at his Dearborn, Michigan estate. Infielder Jackie Robinson had signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers the previous week and was set to break the Major League Baseball color barrier, which he would do just six days later in front of a crowd of 26,623 at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field.

However, it was another story that dominated the headlines in Woodward. The National Federation of Telephone Workers, a loose coalition of telephone operators’ unions, organized a nationwide strike that saw more than 350,000 operators, overwhelmingly women, walk away from their switchboards. The strike, which was in its third day, was poorly planned and executed, but it succeeded in effectively crippling telephone communications across much of the country. In Woodward and surrounding areas, where sparse populations and great distances often left the telephone as the only link to the outside world, the strike dealt an especially heavy blow. The telephone network also served to disseminate vital weather information, as operators passed reports on to one another in times of inclement weather. Outside the telephone office in Woodward, striking operators marched in the fog and drizzle, hoisting signs of protest until the damp, blustery conditions drove them out of the streets.

• • •

As morning turned into midday, troubling signs began to appear over the Texas Panhandle. The barometer at the Amarillo weather observation station plummeted, dropping from 1,008 mb to 993 mb in less than ten hours as a broad, deepening low pressure system moved in from the west. A deep trough dug into the Desert Southwest, producing divergence and lift over the Southern Plains. The trough was amplified by an intense jet streak rounding its base and nosing into West Texas, placing the Texas Panhandle and Northwest Oklahoma in the left exit region and further enhancing upward motion. Mid-level lapse rates steepened as an attendant cold pocket brought cooler temperatures aloft, increasing atmospheric instability. Despite the dreary start to the day, the upper atmosphere was slowly becoming a dangerous powderkeg. All that was missing was a spark.

At the surface, a cold front that had crashed south several days prior and stalled out in Central Texas began to reverse its course. Under the influence of the approaching storm system, it trundled north as a warm front. The blustery wind, which had come largely from the east and northeast, had shifted to the southeast by late morning. A steady stream of warm, humid air rushed in from the Gulf of Mexico, hurried along by gusts that grew stronger as the day wore on. The low, leaden blanket of clouds thinned and pulled apart by mid-afternoon, allowing sunshine to break through and burn off the thick fog. The temperature rose slowly at first. At 6:00 a.m., temperatures in the Texas Panhandle ranged from the middle to high 40s. At noon they had barely broken 50 degrees. As the afternoon progressed, however, the mercury began a rapid rise. The warm front surged north, carried by strengthening south-southeasterly winds and aided by increasing sunshine. By 6:00 p.m., a time when the air would normally begin to cool, temperatures had broken 70 degrees and were still rising.

Reconstructed weather map for 22z (4:00 p.m.) on April 9. Note the winds backing near and north of the warm front. Tornado tracks are shown in red. A star marks the approximate initiation point of the Woodward supercell along the dryline.

Late in the afternoon, the atmosphere found its spark. The simmering air near the surface stirred to life. The leading edge of a very warm, dry airmass blew through the western Texas Panhandle, carried by strong winds blowing from the west-southwest. Observers in Amarillo noted a ruddy, reddish-brown tint in the sky, imparted by dust picked up from the Chihuahuan Desert. Dry southwesterly winds and moist southeasterly winds converged near the dryline, sending plumes of balmy air rising into the skies above the Staked Plain, condensing into cottony, cauliflower-shaped clumps of cloud like a mushrooming atomic blast. Broad anvil tops, sheared off by strong upper-level winds, spread shadows over the scraggly sagebrush like an eclipse. The expanding mass began to rotate, twisted and sculpted by intense winds that veered from east-southeast to west-northwest with height. In a short time, the mountain of cloud stretched more than ten miles high. The central updraft intensified, rocketing skyward and sending overshooting tops into the lower stratosphere. Sheets of heavy rain fell from the base, followed shortly by the audible thunks of golf ball-sized hailstones.

Racing northeast at nearly 40 miles per hour, the incipient storm roughly paralleled a branch of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. A warm, buoyant downdraft descended from the rear flank of the storm, spreading and wrapping back into the updraft. Constricted by this complex airflow and further stretched by the intense upward motion, the rotation intensified and began to lower toward the ground in the form of a wall cloud. At 5:42 p.m., small bits of cloud descended from the rotating maelstrom, reaching toward the earth like long, slender fingers. At the ground, small funnels rapidly condensed and then dissipated, sending plumes of dirt skyward as they seethed and twisted in a complex dance. Two physicians, returning from a conference at Amarillo, noted what they believed was a sandstorm on the horizon. They watched as a “funnel-shaped dust mass” began to take shape from the mess of cloud and dirt about three miles southwest of White Deer.[1] Growing in size, the fledgling tornado bore down on a 61-car freight train bound for the town of Canadian. The nine-man crew, riding in a pair of heavy steel cabooses at the rear of the train, had little time to react. Despite traveling at 25 mph, the tremendous force of the wind quickly overtook the rear of the train, sending the steel cabooses tumbling off the tracks and scattering 19 of the cars through a nearby field. Several of the cars were torn apart, the debris scattered up to half a mile.[2] Miraculously, only two of the crewmen sustained injuries.

Just to the northeast, John Bittle and his wife were visiting his sister-in-law, Alma Thornburg. The tornado struck suddenly, buckling the floors and sending furniture flying through the air. The Santa Fe freight train’s crew had crawled out from the train’s wreckage in time to watch the tornado strike the large farmhouse. In the words of one crewman, “The house lifted a few feet in the air, then hung there and shook like a fish net being lifted out of water.”[3] The house came to rest nearly 30 feet from its foundation, partially collapsed but still standing. Bittle and his wife, despite being pinned under debris, were unharmed. Mrs. Thornburg sustained a broken arm as well as bruises and lacerations.[4][5] According to one report, remains of livestock from the Thornburg ranch were found 30 miles away on a farm in central Roberts County.

On the northern edge of White Deer, two dozen construction workers looked on from atop an eight-story grain elevator as the tornado approached. The slender funnel tore away scaffolding and equipment as it passed just a few hundred yards north of the concrete structure, leaving the workers shaken but uninjured. A garage, several sheds, chicken houses and other outbuildings were leveled, two more homes were slightly damaged and a half-mile stretch of power lines was taken down. W. W. Holmes, a stockman living on the west side of White Deer, was standing in his yard when he heard a rumble “like a fast freight train.” Turning to the northwest, he watched as the twister, which he estimated at about 200 yards wide, passed within three quarters of a mile of his location, “filling the air [with debris] as far as I could see.”[6] Turning north-northeast, the tornado began shrinking and roped out several miles southeast of Skellytown.

The home of Orvil and Alma Thornburg, which was moved 30 ft. from its foundation and moderately damaged. The rear walls (not pictured) partially collapsed.

• • •

Just up the Santa Fe railroad from White Deer, the weather at Pampa was going downhill. An observer at the Pampa Municipal Airport had noted an inky black mass on the horizon, followed by quarter-inch hail and frequent lightning. Booming thunder rolled across the prairie west of town. Steady rain and hail obscured the base of the thunderstorm, but its presence was hard to mistake. Though the White Deer tornado had dissipated, the towering supercell was only growing stronger. Sucking up warm, moisture-laden air like a vacuum, the central updraft continued to rotate strongly. Beneath the wall cloud on its southwest flank, cloud tags formed, twisted and pulled apart as they whirled in toward the heart of the storm. At 6:10 p.m., a broad, dark funnel emerged from the rain curtains north of the airport as the Pampa weather observer looked on. The tornado was moving rapidly northeast, but there was little the observer could do. Special observations could only be transmitted intermittently, and weather observers were not permitted to disseminate such information outside of official FAA channels. Although airline pilots and airport officials across the region may have known that a tornado had been spotted, the residents in its path would remain unaware.

After experiencing hail and thunderstorms for nearly an hour, the weather observer at Pampa reported a tornado north of the station moving northeast at 6:10 p.m.

About 20 minutes after it had formed, the second tornado dissipated in a field eight miles north-northeast of Pampa without causing any major damage. At the Santa Fe railway station in the tiny community of Codman, eight miles southwest of Miami, two railroad signalmen witnessed the billowing storm approach from the west. Beneath the imposing cimmerian base, wispy vortices swirled and grasped at the ground. The rapidly evolving tempest had sprouted five distinct funnels.[7] The signalmen dove for the relative safety of a culvert as one of the funnels, likely a satellite tornado, swept across the tracks just to the west. Shortly thereafter, a hulking twister that witnesses estimated at one mile wide followed the first across the Codman station, sucking up the signal station and throwing 15 work cars from the tracks. A signal gang inside the cars managed to escape serious injury by wrapping themselves in mattresses for protection.[8] One observer near Miami noted three smaller funnels circulating around a very large one, remarking that the twisters looked “like cave stalactites.” Motorists to the southeast of the tornado were treated to an especially striking view as the swirling tempest chewed its way through the countryside, backlit by a brilliant gold and burgundy sunset, as horizontal vortices unspooled, snapped off and quickly dissipated as they rotated around the monstrous wedge.

At the home of Newt Maddox, north of Miami, the storm announced its presence with heavy, wind-driven rain and hail larger than golf balls. The thunder was nearly constant, but as the hail and heavy rain abated the thunder was overtaken by an altogether different sound. The roaring tornado passed close enough to the farm to demolish several outbuildings and tear the roof off the farmhouse. At the Hodges farm, a garage was completely blown away and fence posts were stripped of their bark. A windmill at the Pennington farm was dislodged from its concrete base and bent to the ground. Several thousand chickens were killed when a number of chicken houses were swept away near the Hemphill County border. A vehicle was pushed off the road and into a bar ditch, but the driver suffered only minor injuries. Near the center of the tornado’s path, several trees were debarked and scrubby sagebrushes were stripped down to small stubs. Few other structures were impacted as the tornado tracked for nearly 30 miles before dissipating over the sparsely populated farmlands seven miles west of Canadian. One fatality was reported near the Codman station at which the railroad signalmen watched the tornado approach, but no additional details of the circumstances were given.

Even as the last rays of the dying sun spread pale light across the far horizon, the infernal storm continued on. Its rotating heart grew ever stronger, and even after three hours and at least three significant tornadoes, the storm’s destructive work had hardly begun. After passing through sparsely populated farmlands and railroad junctions, far more than waving fields of grain lay ahead.

• • •

In the early 1910s, Glazier was a thriving town – at least by Texas Panhandle standards – with a population of more than 350, a local bank, a newspaper and several businesses. Its location along the Santa Fe railroad earned it a prosperous stake in the cattle trade, and a large grain elevator made Glazier a central shipping point for wheat as well. A string of bad luck began in June of 1916, however, when a massive blaze – one of three large fires to strike portions of the town in the span of two decades – ignited a feed mill and quickly spread to consume much of the small community’s business district. The westward expansion of the Santa Fe railway soon followed, taking with it most of the cattle and wheat trade which had been its lifeblood. The population slowly dwindled, and by 1947 there were scarcely 100 residents, along with a few small businesses, a flat stretch of highway and little else.

On the evening of April 9, many in Glazier had just finished their suppers when the weather began to turn. The thunder was first to arrive, rolling in and crashing over the prairie town like waves. Lightning illuminated the darkening western sky, coming first in indistinct flashes and resolving into vivid strokes as the storm clouds drew nearer. The rain began just before 7:00 p.m., followed shortly by the pings and thumps of half-inch chunks of hail. At the same time, about 11 miles to the southwest, the storm’s powerful winds once more coalesced into a whirling black mass. Shortly after forming, the violent multivortex tornado struck a construction site on the highway southwest of Glazier. Heavy equipment was thrown and tumbled and left “twisted out of shape” by the wind.[9] Several vehicles were also thrown from the road, and a number of farmhouses suffered damage along the edges of the tornado’s path. At least 75 head of cattle were killed in the surrounding fields, one of which had a narrow strip of roof lath driven completely through its body. In the community of Canadian, resident Fred Cole watched as the incipient tornado took shape and passed just north of town:

“It had fingers going to the ground. It looked about a quarter of a mile across. The fingers would start toward the ground from the cloud and hit the ground. When they hit they broke off and played out. Then a new finger would start. I saw as many as five at a time. You know what it reminded me of? Those things hanging down from the ceiling of Carlsbad Cavern.”[10]

Rapidly expanding to well over one mile wide as it paralleled U.S. Route 60, the massive wedge thundered into Glazier with phenomenal force. The entire town, measuring about half a mile long and a quarter-mile wide, was quickly engulfed by the roaring winds. A row of 12 wood-frame homes on the south side of the highway virtually exploded, tearing away from their foundations and scattering in hundreds of pieces. Some residents sought shelter in basements or storm shelters, and at least one man survived by riding out the storm in his bathtub. Others were not nearly so fortunate. At least seven people were killed in the dozen demolished homes, some of them thrown several hundred yards away. Sixty-four-year-old Ida Farrell was killed instantly when her home was blown apart. Just down the street, her older brother was also claimed by the winds. The bodies of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Scott, both 65, were found together a hundred yards southwest of where their home had once stood.

The destruction was no less complete to the north of the highway. Home after home was demolished, many of them swept away and scattered for hundreds of yards. The residents inside fared no better; bodies were stripped of their clothing, battered by wind-driven debris and rendered unrecognizable.[11] Hardwood trees were debarked and denuded, and even low-lying shrubs were stripped and shredded. According to a widely circulated (possibly apocryphal) report by J. L. Swindle, editor of the Pampa Daily News, the bodies of two people who were together moments before the tornado struck were later found three miles apart. A laundromat was demolished, sending washing machines hurtling through the air over half a mile. Grass and dirt were scoured from the ground in some sections. At least one person was killed when their vehicle was thrown 200 yards from the highway and mangled. Another vehicle was thrown from a driveway and torn apart, the instrument panel and one wheel later found a mile and a half to the northeast. At the same location, a large chain hoist and 20 feet of heavy chain was torn away and thrown some distance, where it crashed through a chicken house and killed several dozen chickens.[12]

Frances Freeman, a resident of Canadian, was among the first to arrive in Glazier. Having been unaware of the storm’s passing, she’d come to visit her brothers, Dee and Tom Eubank. Sixty-year-old Dee, who worked at a local filling station and store, and his 68-year-old brother, Tom, had lived much of their lives together with their ailing mother, whom they’d taken care of until her passing in September of the previous year. When Frances arrived, she encountered a scene of utter desolation. Just two of the town’s 50-plus homes were left even partially standing. The Eubanks’ home was completely destroyed, and Dee and Tom were found dead some distance away. Ten days after the storm, Frances’ husband Carl received a letter from a Harold Bragg near Wilmore, Kansas – more than 115 miles to the northeast of Glazier. Enclosed was a paper and a photo that Bragg had found in his pasture. The paper, bearing Carl’s name, had been inside a steel filing cabinet at the Eubank home when the tornado swept it away.[13]

At the Glazier filling station, owner Alfred Jackson had seen the tornado approaching as he worked on servicing a car. Sprinting through the station’s store, he urged the patrons into the basement. Nine adults and seven children took refuge as the structure overhead began to disintegrate. So great was the suction of the wind that two people were pulled out of the basement, one of them thrown 300 yards to the east and the other 250 yards to the north. According to Jackson’s wife, those inside the basement had to lay flat against the ground in order to avoid being sucked away.[14] Clint Wright and Art Beebe, construction workers with the Santa Fe railroad, had taken shelter in Wright’s home near the highway. Both were also sucked out of the cellar and thrown some distance. Perhaps the luckiest people in Glazier were Mr. and Mrs. Everett Howard. They were in their home with their three children when the roaring wind bore down. The windows began to rattle and shake. The walls pulsed as if they were breathing. Mr. Howard and his son held back the door with all their might as the windows blew in, sending glass scattering through the house. After the wind subsided, the Howard home was the only one in Glazier left standing. No one inside was injured, and the Howards continued to live in their house after extensive repairs.

After devastating the entire town of Glazier – killing 17 people and injuring 45, nearly 60 percent of the total population – the tornado quickly swept on along the highway. Four miles east-northeast of Glazier, the two-story home of Charlie Harrell was swept cleanly away and “scattered in every direction.” His wife was found dead in a field after being thrown from the house. The oldest child, seven-year-old Ruth Jean, carried her eight-month-old brother and led her two sisters, ages four and two, a quarter of a mile to the highway in search of help. Next in line for the tornado was the tiny railroad outpost of Coburn. Work cars which housed a railroad construction crew were thrown off a section of siding, including a bunk car in which a cook was killed. Farmhouses, barns and outbuildings were also swept away along the highway in this area. Just to the northeast another train was wrecked and pushed off the rails, causing several injuries but no fatalities. In the 20 miles the tornado had been on the ground, it had claimed 19 lives and left complete ruin in its wake. One witness, upon seeing Glazier, described the scene as resembling post-war Lidice, a village in Czechoslovakia which was completely obliterated by a Nazi SS task force in 1942. Twice more a similar scene would play out over the following hour and a half, and the human toll it exacted would be on a scale scarcely seen before or since.

• • •

The town of Higgins was roughly bisected by the Santa Fe railroad tracks, with wood-frame structures to the south and large brick and mortar businesses and other structures to the north. As twilight faded into dusk over the Texas Panhandle, few of its 750 residents took note of the mountainous black mass encroaching on the horizon. Word of the calamity at Glazier had not – indeed, could not – spread to the small town straddling the Texas – Oklahoma border, and only the constant strobe of lightning and low, rolling boom of thunder gave notice of the approaching threat. Patrons filed into the Alamo Theater or enjoyed themselves at the local pool hall as a light shower slowly grew into a pulsing downpour. The wind, which had been stiff and gusty all day, whistled through the streets and alleyways, whipping the rain into angry whirls. Hail larger than golf balls fell to the earth like tiny meteors, pounding on roofs and shattering on the pavement. Still, there was little concern; thunderstorms were to be expected any time warm, muggy spring air blew in from the Gulf.

On the southwestern edge of town, C. C. Fitzgerald struggled to drive through the wind-whipped rain. A large hailstone shattered his front window, sending him scurrying into the back seat in search of cover. Moments later the rear window, too, exploded into shards of glass. The wind became violent, rising to a howl as it rushed in toward the massive, debris-clogged vortex passing just to the north. The intense inflow winds shook the car and threatened to send it tumbling, but fortune was on Fitzgerald’s side. When the winds abated after several minutes, the scene was striking. The row of homes lining the road had disappeared, swept off their foundations and scattered by the wind. Trees were debarked and twisted into grotesque forms, utility poles were snapped just above ground level, fence posts were pulled from the ground and stripped of their bark, and a number of vehicles and pieces of farm machinery lay strewn about in crumpled heaps.

The monstrous multivortex tornado had grown to one and a half miles in width, and it quickly swallowed the town of Higgins whole. The primarily residential southern half of Higgins offered virtually no resistance. The multiple vortices cut several swaths of extraordinary devastation, leaving some structures relatively unscathed and completely obliterating others. Wood-frame homes were ripped apart, splintering into fragments and adding to the tremendous amount of debris already caught in the circulation. More than three dozen people were killed, including two people who were thrown 500 yards from their disintegrating home. Victims were stripped of their clothing and badly disfigured by the combination of wind and granulated debris. A number of families suffered multiple fatalities, including all five members of the Boyd Wingfield family. Bill Robertson, a machinist and welder, was at home with his family when a dull rumble in the distance grew into an ear-splitting roar. He and his family scrambled into their storm shelter just as the tornado swept their home away. Next door at Robertson’s machine shop, the tornado’s fury was on full display. The shop was completely demolished, and a four-and-a-half ton tool steel lathe was torn from its anchoring and snapped in half.[15][16]

On the north side of the tracks, Higgins’ brick and mortar business district offered only slightly more protection. The section of the business district nearest the tracks “crumbled like sandbanks.” The train depot was damaged and several cars were thrown from the tracks. Two churches and a string of businesses collapsed, sending heavy bricks flying through the air and into the streets and trapping dozens of people underneath the rubble. A car dealership was struck and more than 40 cars were totaled. The Alamo Theater was completely devastated, killing several unsuspecting patrons and trapping dozens of others inside. The Laubhan & Schwab hardware store was collapsed and ripped apart. The pool hall was leveled, trapping four people and sparking an inferno that combined with ruptured gas lines to quickly spread through the shattered remains of surrounding structures. The sheer scale of the devastation prevented emergency crews from battling the blaze, and by the time the flames died down the fire had consumed what was left of three blocks through the middle of town. When rescuers eventually reached the pool hall, they found the charred bodies of the four trapped victims.

One of the first eyewitness accounts of the scene at Higgins came from TWA pilot Roy L. Thrush. Flying a Los Angeles – Kansas City route over the Texas Panhandle at around 2:45 a.m., Thrush relayed:

“I started looking for Glazier, Tex., but the only building still standing was a filling station on the highway. The rest of the village, from what I could tell, was obliterated. A few miles further, at Higgins, Tex., which is between Glazier and Woodward, all I could see was a schoolhouse and two or three other buildings. Smoke was over the town, and there were fires in several locations. It looked as if it had been almost wiped out.”[17]

The destruction was as chaotic and random as it was absolute. A few of the more fortunate structures in town sat largely intact, juxtaposed with long stretches in which very little remained standing. Almost three-quarters of the town was rendered uninhabitable, much of it completely leveled. Front yards, stripped of vegetation, became streaks of muddy slop in the heavy rains that followed. Overhead power lines were “completely blown bare of all insulation.”[18] Disease spread quickly among survivors forced to live in cramped, unsanitary conditions in the immediate aftermath. Fifty-one people were killed at Higgins and more than 250 were injured – a full 40 percent of the town’s population. At least 70 Texans lay dead by the time the storm crossed the Oklahoma border into Ellis County, two hours and 84 miles after the first tornado sprouted from the sky at White Deer.

• • •

Thunder rattled the windowpanes as the Kolanders sat together in their family room. Having no electricity and little in the way of outside entertainment, the family of six found other ways of enjoying themselves. Four-year-old Doug and eight-year-old LaNita sat on their father Henry’s lap as he told stories and sang to them in their native German. Ramona and her brother Floyd chatted with one another while their mother Stella, never one to sit idle, finished up some chore or another around the house. The children had taken note of an odd viridescent tint in the western sky when they stepped off the school bus around 5:00 p.m., but they’d thought little of it at the time. Spring was always stormy in Oklahoma, and the hardy folks who survived the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl were hardly the type to fear a little thunderstorm. Even little Doug seemed unfazed, remarking “If God wants it to rain, it will” as he said goodnight and readied for bed.

Quarter-sized hail pinged and thumped on the roof as Ramona led her younger brother upstairs and read him a bedtime story. The sharp cracks of thunder became louder and more frequent. Lightning flashed and crackled like flashbulbs outside the window. The old farmhouse shuddered and creaked. The strong smell of damp prairie dust, whipped up and carried on the wind for many miles, soon permeated the house. The adobe and wood-frame structure gave another shudder, as if shoved by some great invisible hand. Realizing the danger the approaching storm posed, Henry and Stella headed for the stairwell to get their children. At the same time, Ramona grabbed Doug and also headed quickly for the stairs. Pausing momentarily to blow out a kerosene lamp on a nearby table, the floor under her feet suddenly and violently fell away. Ramona blacked out.

When she regained consciousness, she found herself walking aimlessly in the yard. Drenching rain and hail fell over a surreal scene, illuminated only by frequent strokes of lightning. Piles of rubble were strewn about where the house and garage once stood. She was disoriented, her body weighed down by fatigue and bruised and lacerated from debris strikes. She leaned against the trunk of a mulberry tree to rest but was interrupted by a low moan calling out over the rumbling thunder. Henry Kolander lay trapped beneath a thick adobe wall, pinned up to his chest and unable to move. Floyd and LaNita tried desperately but were unable to lift the wall. Retrieving a jack from the car – incredibly still parked in its space despite the entire garage having been blown away – Floyd and Ramona tried and again failed to move the heavy, crumbling wall. There was no sign of little Doug or his mother. A sickening wave of realization washed over Henry, which he voiced to his remaining children: “they must be dead.”

Ramona set out into the storm to seek help from a neighbor, Mr. Ehrlich, about a mile to the north. When she arrived and gave word of what had happened, she collapsed in shock and exhaustion. She was taken to the hospital in Shattuck where she was initially placed in a corridor among the injured who were not expected to survive. She’d sustained a number of contusions and lacerations, but she was eventually treated and made a full recovery. At the Kolander farm, Mr. Ehrlich arrived with help and finally succeeded in lifting the wall that had trapped Henry. They discovered his wife’s body at his feet, not visibly injured except for a bruised lip. Her neck had been broken when the wall near the stairwell collapsed. Four-year-old Doug was later found crushed underneath a door in the yard, nearly every bone in his body broken. Floyd and LaNita sustained only minor injuries, and Henry eventually recovered in the hospital.[19]

About 15 miles to the northeast, Margaret Larason had just finished putting her two children, six-year-old Tim and five-year-old Anne, to bed for the night when the upstairs windows blew out. She and her children took shelter under blankets in the kitchen as the tornado roared by very close to the north. The house rattled and creaked as if it were being torn apart at the seams, but it did not fall. The porch had ripped off and flattened itself against the front door, blocking the Larasons’ exit and forcing them to wait for a neighbor to extract them. They emerged to extensive damage scattered around the property. A full 1,500-gallon water tank weighing more than 14,000 pounds was unmoored by the winds and “vanished.” A metal windmill anchored in cement was bent almost flat to the ground. Tough, weather-beaten sagebrush was chewed down to the stump. In the same area, the homes of Robert and Harold Cully were swept away. Robert’s wife, Geneveine, and Harold’s six-year-old son Ned were killed. In all, more than 50 homes were demolished throughout Ellis County, killing six residents and seriously injuring dozens more. The storm had spared most of the county, missing the population centers of Shattuck, Gage and Fargo just to the south, but the biggest town of all still lay ahead.

Death was coming to Woodward.

• • •

The switchboard at the Woodward telephone office blinked to life. It had been a quiet, unremarkable night for chief operators Grace Nix and Bertha Wiggans, who were tasked with handling emergency calls in the striking workers’ absence, but their concern was beginning to grow. The first call had come from an operator at Shattuck: “It’s storming out here, are y’all alright?” The question seemed odd. A light, breezy rain was falling outside the Woodward office and flashes of lightning could be seen in the distance, but there was little immediate cause for alarm. News of the devastation at Glazier and Higgins still had not spread. In minutes, however, the reason for the question became more clear. Thunder clattered and ricocheted through the streets. The stiff, gusty wind whipped up into a gale. Another call followed shortly thereafter, placed by an operator 25 miles to the southeast in Cestos: “There’s a dark cloud over Woodward, it looks terrible!”[20]

The city of Woodward lay nestled in a subtle depression in the low, rolling terrain on the western edge of the Gypsum Hills. The broad, squat hills rimming the city, according to Native American legend, served to protect Woodward from the violent storms that plagued much of the territory. On the muggy evening of April 9, those storms were the furthest thing from residents’ minds. As on every Wednesday night, both the churches and the movie theaters were packed. Three hundred people packed the Woodward Theater to see the 1941 Ingrid Bergman thriller Rage in Heaven. Two hundred others settled in for The Devil on Wheels at the Terry Theater. The pool hall was loud and raucous as usual. About a dozen people milled around inside the Main Street drugstore, where drug company representative H. C. Carnahan was discussing an order with the proprietor. On the north side of town, Erwin Walker drove to his shift at the Oklahoma Gas & Electric plant. As the manager he didn’t normally work nights, but he’d elected to take the shift as a favor to a friend.

Agnes Hutchinson with her sons, Jimmie Lee (left) and Robbie, taken about a year before the tornado.

At the Oasis Steakhouse, 28-year-old waitress Agnes Hutchinson was deep in thought.[21] She worked the night shift while her husband Olan worked days, ensuring that someone was always home with their two sons, five-year-old Jimmie Lee and eight-year-old Roland. Her husband always brought the children to the diner to have a soda and keep their mother company, and Agnes was concerned that they still hadn’t stopped. She picked up the phone to call and check in, but rather than the customary “Number, please” so often heard before the strike, the operator greeted her tersely: “No, not unless it’s an emergency.” Agnes had seen the faint outline of a great cloud bank towering on the horizon during her drive to work, adding to her concern. The near-constant barrage of lightning southwest of town was on full display when she stepped outside. Pacing nervously, she considered quickly heading to her home a few blocks away, but she returned to work and resolved to push the worry and anxiety from her mind.

At the local high school, a brass quartet had just wrapped up rehearsal for the big Tri-State Festival scheduled to take place in Enid, Oklahoma the following day. Sixteen-year-old Paul Nelson hopped on his bike and pedaled toward home, while two other students stayed behind to practice. Paul pedaled hard as the wind whipped drenching rain in his face. Chunks of hail pelted his head and back. Just to his south, the storm grew into a howling screech. The tornado, now an almost unfathomable 1.8 miles wide, quickly climbed the small hill – handily dispelling the Native American myth that the mound offered any protection – and thundered into the western half of Woodward. The United States Field Station was swept up and torn apart. It crossed Experiment Lake, allegedly sucking up so much water that the lake’s level dropped by a foot. Thick mud, tinted a rusty color by the red clay soil, spattered anything left standing on the northeast side of the lake.

The switchboards at the Woodward telephone office suddenly erupted with activity. For chief operators Grace Nix and Bertha Wiggans, it was clear that something major was taking place. Before they could begin to address the flurry of calls, however, the boards fell silent. The glass windows bowed, pulsed and then shattered. Scraps of tar paper, glass, wood and other debris rushed into the office. Awnings and shingles raced by in the street, driven on by a violent wind that had risen to near-deafening levels. Patrons at the drugstore on Main Street shared a similar experience. H. C. Carnahan recounted a “loud swishing noise, like the sound of escaping steam.” Vehicles and debris tumbled along the street outside, as did merchandise from several of the stores just to the north. The windows on the south side of the building blew out, and most of the second floor sheared off and tumbled into the street. No one inside was injured, but they emerged to something resembling a war zone.

Large sheets of tin peeled off and flitted away from the exterior of the Oasis Steakhouse. The windows bulged and heaved before shattering, sending glass flying like shotgun blasts and providing entry for the angry winds. Scraps of paper and debris filled the air. Plates and dishes clattered and smashed on the floor. The roof tore off and broke apart, followed quickly by the exterior walls. Many of the people inside, including Agnes, went tumbling out into the darkness, propelled along by the infernal storm. When she came to rest, wrapped around a telephone pole, her thoughts immediately turned to her family. Glancing up in the direction of her home, her heart sank. She could see almost to the horizon, the line of buildings that would normally block her view having been completely razed. She ran in the direction of her neighborhood, navigating by lightning flashes and picking her way around the rubble. A naked man – her neighbor – crawled on the ground, calling out for help. A bolt of lightning flickered across the sky, illuminating the bare foundation where her home had been minutes earlier.

Intense damage viewed from the approximate location of the Hutchinson home and looking east. Note the completely debarked and denuded trees.

Following the streak of debris to the northeast, Agnes came upon the sight she had unconsciously feared. Her husband and two young boys lay in crumpled heaps in the bottom of a broad grader ditch. A call to her husband was met only with a raspy gurgle as the last gasp of air seeped from his mouth. He was dead, his head partially caved in by the blunt force of airborne debris. Her youngest boy, Jimmy Lee, was unresponsive. Only eight-year-old Roland showed signs of life, pleading for help as he bled profusely. Reeling from shock, her starchy white uniform caked with blood and mud, Agnes stumbled to the road to flag down an oncoming car. Two men helped load her husband’s body while she carried her boys, one in each arm, to the waiting vehicle. Arriving at a makeshift staging area for the wounded and dying, she carefully removed Jimmy Lee’s muddy, rain-soaked clothes, cleaned him as best she could, and wrapped him lovingly in a blanket. She carried him to a truck waiting outside to transport the dead to area morgues. A man asked for the blanket, reasoning that it did no good to the dead child. Agnes was incensed. “I know it won’t! I’ll pay for the damn blanket, but the blanket stays!”

• • •

Erwin Walker had only been working his shift at the Oklahoma Gas & Electric plant for a short time when he caught a glimpse of the massive, roiling cloud tearing through the southwest side of Woodward. Witnessing nearby power lines flailing and threatening to snap, Walker reacted quickly. Rather than seeking shelter, he sprang into action and ran for the master switch. He managed to throw the switch just as the destructive winds collapsed large portions of the OG&E plant, succeeding in cutting power to the hundreds of lines that might otherwise have electrocuted people or sparked deadly fires. When rescuers began to dig through the rubble of the power plant, they found Walker’s body still near the switch. Walker’s selfless actions likely saved many lives across the city and prevented even further devastation. Even greater disaster was narrowly averted when the giant wedge’s most violent winds narrowly missed the Woodward and Terry theaters. The wind still collapsed both buildings, but many of the moviegoers inside were able to escape serious injury by sheltering beneath the sturdy metal-frame seats.

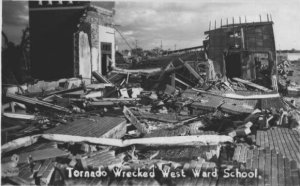

Few others in Woodward would be so fortunate. The pool hall was completely demolished, killing the five people inside and mangling them so badly that they had to be identified by their wristwatches. The high school, too, was destroyed, and the two band members who stayed behind to practice were killed. As the tornado flattened homes and granulated debris, the deaths rapidly mounted. More than a dozen families lost multiple members, including four members each of the Catlett, Fiel and Harper families. Victims were killed in their homes, in the streets and in businesses across Woodward. One woman was thrown 500 yards from her home and wrapped tightly in a length of barbed wire fence. Another was pinned to a tree by a shard of two-by-six driven through her chest. Some victims arrived at staging areas bristling with debris, small shards of wood and glass and other materials covering their bodies like porcupines. At the Woodward railyard, large steel oil tanks were torn from their anchoring and ripped apart. On 8th Street, a 50-foot industrial steel boiler weighing nearly 20 tons was also torn from its moorings and thrown a block and a half.[22] Most of the nearby North Canadian River bridge was blown as well, restricting travel in the area. To make matters worse, fires erupted in downtown. The Big 7 Electric Company was engulfed, as were the Big 7 hotel, the Armour creamery, the Rainey-Davis wholesale firm and a large lumber yard.

Dr. Joe Duer, the chief physician at Woodward’s local hospital, had been enjoying dinner with his wife at Gill’s Cafe when the weather outside took a turn for the worse. Owner Gill Gillard stole a glance at the barometer hanging on the wall – the pressure was falling more rapidly than he’d ever seen. Debris had begun swirling through the air outside the window, and Dr. Duer quickly recognized the howl growing out of the blackness. Duer and Gillard hurried the other patrons to cover just as the tornado swept through. Duer rushed to the hospital, where the wounded had begun arriving in a slow trickle. Two doctors in the hall treated a man whose scalp had been peeled back. A nurse comforted a young woman with a compound fracture of her arm. A veteran corpsman who served with the Marines at Iwo Jima, Duer immediately began preparing to triage the injured he knew would come. Within moments, the hospital was inundated with waves of the injured and dying. When the hospital’s 28 rooms were filled, the injured were lined up in hallways, utility rooms, offices and anywhere else spare room could be found. With so many critically injured victims to attend to, there was no time for the dead. Bodies were unceremoniously moved out of the way, pushed under beds and into corners until volunteers could carry them out.

With no running water and no electricity, doctors and nurses worked under grueling conditions. Surgeons operated by candlelight, doing their best to clean gaping wounds with what little water could be carried in from elsewhere. Those who were able assisted nurses in stanching bleeding and splinting fractured bones. Those who were too badly injured and not expected to live were given morphine shots to bring some small measure of comfort. On the front lawn, rows of motionless forms lay covered in rain-soaked sheets. It was much the same at the Armstrong Funeral Home, where broken bodies had been stacked like cordwood. Workers did their best to clean blood and dirt from faces to make the identification process easier, but little else could be done. Occasionally the grim silence was punctuated by screams and sobs — another survivor had found a loved one. Along with the hospital, the Baker Hotel was converted into a secondary treatment center for the less gravely injured. Any truck left in operating condition was pressed into service, either carrying the wounded to area hospitals or collecting the dead to be transported to the morgue. In a rare piece of good fortune, the drenching rains that followed in the storm’s wake helped to suppress the fires that had started downtown.

L. L. Aurell, wire chief for the Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, was huddled in his basement with his family when the storm blew his home away. Quickly realizing the magnitude of the unfolding disaster, Aurell grabbed his equipment and set off into the storm. Reaching a section of line not completely destroyed by the tornado, he clambered up a telephone pole and held the broken line together. Despite the angry thunderstorm still raging around him, he sent first word of the calamity to the outside world.[23] Still, darkness obscured the true scale of the desolation. By sunrise, the magnitude of the disaster was clear. One hundred seven people dead. More than a thousand others injured. A two-mile wide swath of Woodward reduced to ruin, with five hundred homes completely destroyed and another 650 damaged. Never before or since has Oklahoma, perhaps the most tornado-prone region on Earth, suffered more loss in a single tornado.

The tornado, or another in the same family, continued on for another 43 miles after laying waste to Woodward, eventually dissipating about 13 miles northwest of Alva. Destructive to the very end, the tornado injured 30 people and destroyed several dozen homes at White Horse. The supercell continued across the Kansas state line, producing two broad areas of intense downbursts and possibly embedded tornadoes in central and eastern Barber County. There were other storms as well. An airline pilot traveling from Amarillo to Wichita reported that numerous thunderstorms covered an area approximately 100 miles in diameter, which “appear[ed] dangerous to flying with severe lightning and large thunderheads.” A large tornado tracked for 24 miles across the sparsely populated southern tip of Roger Mills County, OK, destroying two homes and several barns and seriously injuring a husband and wife. Another struck about seven miles east of Mooreland and destroyed a number of barns. At 8:15 p.m., a large and violent tornado touched down just north of Meade, KS and tracked to the northeast for 36 miles, sweeping away about a dozen homes near Fowler and Mineola and injuring three children. A pair of tornadoes did moderate damage between the towns of Marion and Florence in Marion County, before the final tornado of the night destroyed several barns and unroofed homes on a 16-mile path southwest of Topeka.

• • •

The Glazier – Higgins – Woodward tornado of April 9, 1947 still stands as the sixth deadliest in American history, claiming at least 181 lives in total. The damage at Glazier was so severe that it was never rebuilt as a town. For the people of Higgins and Woodward, recovery was a long, slow, painful process. Rescue efforts at Higgins stalled for some time due to torrential rains and street flooding. The sheer number of dead so overwhelmed the small town that funeral services had to be delayed when graves could not be dug fast enough. An arctic airmass swept through in the days following the storm, bringing up to four inches of snow to the area and throwing yet another wrench in the recovery process. Aid came swiftly, however, and donations began pouring in from across the nation. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were raised in Texas and Oklahoma, and doctors and supplies from hundreds of miles away rushed to the stricken areas to render aid. An Army Air Corps barrack at Woodward was converted into an emergency housing project, serviced by the Red Cross and Salvation Army and affectionately dubbed “Tornado Town” by the dozens of families who called it home.

Video detailing Woodward’s “Tornado Town.”

The material loss was staggering, but the emotional toll was hard to appreciate for those who had not lived through it. Agnes Hutchinson fell deeply into shock after her husband and youngest son were killed. She did not cry at the funeral, nor did she cry at all for some time. She kept herself constantly busy, cobbling together a small shack with whatever building material could be salvaged from the wreckage of the previous home, the home her husband had built for his family with his own hands. She, like so many in Woodward, could not sleep without keeping one eye focused on the window, fearful the swirling winds would return and determined to be ready. Agnes could never forget, but she slowly healed, and within a few years she’d remarried and had four more children. She and her family made their new home in Udall, Kansas. At 10:35 p.m. on May 25, 1955, the roaring winds did return. One of the most violent tornadoes in history obliterated much of the small town, killing 80 people. Agnes again lost her home and much of her property, but her family was safe. After the immeasurable loss she suffered on that early spring night in Woodward, that was all that mattered.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

^ 1: “Local Doctors Have Grandstand Seat for Twister.” Pampa Daily News, April 10, 1947.

^ 2: “Higgins, Woodward Set Afire; Train is Blown off Tracks.” The Amarillo Daily News, April 10, 1947.

^ 3: “Disaster: Like a Fast Freight.” Time, April 21, 1947.

^ 4: “Tornado Buckles Home, Cuts 300-Yard Swath in Texas.” The Tipton Tribune, April 10, 1947.

^ 5: “Storm Sounds Like Freight Train as It Strikes Town.” El Paso Herald-Post, April 10, 1947.

^ 6: “Eyewitness Tells of Beginning of Disastrous Tornado.” The Sandusky Register, April 10, 1947.

^ 7: “Plains Tornado.” The Amarillo Daily News, April 10, 1947.

^ 8: “Santa Fe is Commended for Relief Work.” The Amarillo Globe, April 15, 1947.

^ 9: “Texas Storm Damage Runs Into Millions.” The Escanaba Daily Press, April 11, 1947.

^ 10: “Mercy Fund Skyrockets to $100,000 Mark.” The Amarillo Daily News, April 15, 1947.

^ 11: “Storms ‘Level’ Several Towns; Damage High; Toll Mounting.” Lubbock Morning Avalanche, April 10, 1947.

^ 12: “Levi Holt Tells of Glazier Storm.” The Hemphill County News, April 25, 1947.

^ 13: “Carl Freeman Gets Interesting Letter.” The Hemphill County News, April 25, 1947.

^ 14: “Alfred Jackson’s Story of Storm.” The Hemphill County News, April 15, 1947.

^ 15: “Survivors Wander Dazed and Helpless at Ruins.” The Amarillo Globe-Times, April 10, 1947.

^ 16: “Stunned Victims Unable To Comprehend Disaster.” The Amarillo Daily News, April 11, 1947.

^ 17: “Damage Heavy in Storm Area.” Lubbock Morning Avalanche, April 11, 1947.

^ 18: “Local Man Tells of Tornado and Asks Donations.” The Canyon News, April 24, 1947.

^ 19: “Tornado Stories.” Woodward County, OK History and Genealogy. http://www.usgennet.org/usa/ok/county/woodward/tales.html (accessed March 10, 2014).

^ 20: “Woodward County Tornado of April 9, 1947.” Oklahoma Genealogy Trails. http://genealogytrails.com/oka/woodward/hist_disasters_tornado.html (accessed March 13, 2014).

^ 21: Giddens, Agnes. Interview by Oklahoma Historical Society. Oklahoma History Center, 1983.

^ 22: Based on measurements taken from a Weather Bureau survey of the tornado damage.

^ 23: “Twister Cuts Swath Across Two States.” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, April 10, 1947.

Yet another exceptional account of a historic tornado, well done Shawn. For me this account gave a lot of insight as to why the death toll was so high. This tornado seemed to be an exceptionally large multi-vortex beast based on testimony.

Any thoughts or comments on the size and velocity versus the areas impacted and co-relating death/injury toll? I always wonder how much the integrity of structures from that era affect the death toll and injury count.

Did any recommendations or policy change come as a result of this tornado?

Thanks Jason. I think, as with the Tri-State tornado, Joplin, etc., it’s just another case of a series of unfortunate circumstances adding up to a large-scale disaster. A large, violent tornado striking a populated area is almost a guaranteed recipe for mass casualties, even more so when the tornado is nearly two miles wide and of legitimate F5 intensity. The fact that this happened near/after sunset, traveled in excess of 40 mph and generally struck with only a few seconds warning only exacerbated the situation.

The construction quality was probably questionable in many cases as well. Some homes in that era were actually pretty well-built, but most were not. I suspect if we were to apply the modern EF-scale ratings, many of those homes couldn’t be rated much higher than EF3. That’s not to suggest that this wasn’t a violent tornado – I think some of the damage photos/accounts speak for themselves, and I have no doubts about the F5 rating whatsoever – just that it probably wouldn’t take much to collapse some of those structures. In fact, in some photos you can see homes that probably were knocked over by inflow or RFD winds well away from the core damage path.

There was some increased pressure on the government to find a way to provide warning for tornadoes after this event, but not much really changed. The word “tornado” was still banned from official forecasts and many still felt that it would do more harm than good to try and predict them. The two big catalysts that finally got things moving were Miller & Fawbush’s now-famous forecast at Tinker Air Base on March 25, 1948 and the devastating tornadoes in May and June of 1953. I’ve actually been working on a post related to tornado forecasting history, maybe I can finish it sometime.

Anyhow, those events eventually led to the implementation of tornado forecasts and warnings, the establishment of SELS (forerunner to the NSSFC and eventually SPC), etc. I don’t think anything changed at the FAA though, which is odd.

Great Article,.Shawn……My dad ( Riley Stewart ) was hunting that night north of town…Came back and helped people, out of the destruction…….

Thanks Ben, your dad must have had quite a story to tell after that. It’s hard to imagine the sheer scale of the devastation.

Great job as always. I always realized that this was a violent tornado, but these pictures have me more impressed than I was previously. The fine granulation of debris in Glazier is some of the worst I have seen photographed. The mention of what happened to that lathe is pretty jaw-dropping as well.

Yeah, I wish I could have found a photo of that lathe to get a better idea of exactly what happened. The story is well-corroborated across several sources though, so I felt pretty confident including it. I was somewhat surprised at how violent the tornado was at all three towns as well. I don’t know why I ever thought otherwise, but before digging into it my impression was that it wasn’t especially intense compared to other violent tornadoes. My opinion has definitely changed.

The Weather Bureau at the time said that it was one of the “strongest storms in history” after they surveyed it and estimated the wind speeds reached 450 mph. We know that’s wayyy too high now, obviously, but I think their statements are pretty telling nonetheless.

Nicely done. Enjoyed reading it.

Thanks Mike, appreciate it. If you happen to come across those observations from Gage I’d still be interested in seeing them sometime.

Very good work! I won’t bore you with a lot of blather about my personal (family) history with this event, just accept my deepest appreciation for the work you have done.

Thank you very much, Keith. If you’ve got a story I’d love to hear it!

Good account. I did see one error. Iwas in the Terry Theater, and the roof didn’t collapse. It was pretty full but no one was injured.

Thanks for commenting, Velden. I’ll have to correct that. Would you mind sharing what you remember of that night sometime? I’d love to hear about your experience.

Shawn, I know Velden and I knew two other boys who were at that movie and told me about walking home after the storm. They lived on the southeast side of town and I lived on the south central side, where there was less damage than over on the northwest side.

I believe it was the marquee in front that collapsed. My sister was in the theater that night. As a telephone operator, she went to the telephone office directly from the theater to see if she could help. Her name was Ovie Hughes. The Fothergill name is familiar. I went to school with a Fothergill but it seems like his name was Bob.

My grandpa was born on this night in Laverne after the tornado went through Woodward.

My mother-in-law was at the Terry Theater that night. Luckily she was unhurt as were her family members. She recounts about slicing lunch meat at a local grocery store for weeks to help feed the hungry.

My husband’s family’s house was and still is at 7th and Washington. The house was rotated off the foundation and then put back. I have more pictures from them coming up out of their tornado cellar when it was over. The pictures give me chills.

I was very happy to find this and will post my personal story a little later. I was a child living in Woodward on Webster St. I am also interested in personal stories from the storm as I am working on a series of character poems in the voices of those who experienced it. I’m hoping that some who read this will post them here with permission for me to use them or will email them to me. del.cain@sbcglobal.net

Del, having grown up in Woodward, I’ve always been respectfully fascinated with the history of this tornado and its aftermath, and I’d love to read your works of poetry after you get it finished, if you don’t mind that is.

My mother, Mary Ann Kelln Trenfield, went with her friend, Mary Catherine Mason (owner of Mason’s Funeral Home in Shattuck) to Higgins to help recover bodies. They had only one herse and had to comandeer pickups to bring in the bodies. I was eight years old and remember it vividly! It seemd to hit everywhere and then jump over Shattuck before going back on the ground.

My Mother-in-law was an RN at the Shattuck hospital at this time. After the hospital was filled they made beds on the lawn. My husband remembers sitting on the balcony of the hotel watching planes land on the highway bringing doctors, nurses and supplies.

Dude, you should be an author. I’m serious.

lol

Ha, thank you Luka. I’d like to write a book on historical tornado events if at some point I can afford the cost of traveling to hunt down information/photos and the fees to use the photos. I suppose the photos aren’t entirely necessary, but I think they add a lot to the story.

Every time I hear or read about this devastating storm, I cry. My dad was just 10 years old when this happened and he lost his four year old brother and his mother that awful April night. I never got to meet my grandma or my uncle and this storm colors everything I ever heard or learned about them. Such sorrow!

Hi Katherine, thank you for commenting. You’re Floyd’s daughter? I can’t imagine what your father must have gone through, that’s a terrible thing at any age, but especially for someone so young.

I think this tornado is the worse one. It possibly could be an F6. So terrible. That’s wht I’m so scared of storms!!! We had one May19,2013 an F4.

every town in several states need to build a reenforced concrete bunker under ground It could serve as other things, a clinic, and a kitchen, and as a massive tornado shelter. Warn churches, schools, and theatres asap. people who didn’t hear the warning, run into the nearest

big building with an unlocked basement. Kneel against interior walls. private donations, and help from the state and federal facilities could finance this project that is long overdue.

Many communities are now building communal storm shelters, especially if they have a high percentage of people living in trailer parks and other high-risk structures. There are two problems, though. The first is that it’s very expensive to build a sufficiently large shelter, though that’s a hurdle that can be overcome. The second is that you could end up with hundreds or even thousands of people getting in their cars to try and drive to the shelter any time a tornado comes. That puts them in serious danger (a car is not a safe place to be) and can cause traffic jams, car accidents, etc. that can exacerbate the situation.

That doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done, but there are lots of potential problems to work out before doing something like that. Unfortunately it’s one of those things for which there may not be any easy answers.

This was an amazing article! Your work never ceases to amaze! Are you currently working on any new projects? Also curious if you’re planning on writing an article about the 2013 Moore tornado?

Thanks Jimmy! I’m currently working on two new articles, one on a tornado outbreak and one on a little-known but exceptional tropical cyclone. I don’t do many recent events, but the Moore tornado is definitely on my to-do list at some point. Extremely violent, and it was probably one of the more well-documented tornadoes we’ve ever seen.

I was only about 11 and lived a few miles north of Glazier. Several members of our family went to Glazier that night. My brother and I helped load bodies into pickups to take to Canadian. The live ones were taken in automobiles or what ambulances were available. A very sad time.

As I recall the service station had at one time been a bank. The vault was all that was left standing. Farther down the highway toward Higgins was a small concrete jail, it was still standing.

Thank you for your great work on this! My Great Grandmother, Leah Roth was an American Red Cross volunteer during the recover efforts. Her husband, my Great Grandfather Ray Roth, had a sister and her family in Canadian at the time and was originally from Enid, Oklahoma. This system tore a path through places my Great Grandparents and their families had lived from Canadian, Texas to Ellis County, Oklahoma. This is nice historical accounting and the American Red Cross film is a bonus I didn’t expect!

Great story, I learned a lot about an event which has long been part of my extended family’s lore. Through my mother I am descended from both Rutledges and Carmans who raised large families in Woodward County starting just before the turn of the 20th century. Dozens of my relatives were present in the area during this storm though to my knowledge none were killed.

In particular my great-grandfather Calvin Delbert “Del” Carman and great-grandmother Ida Carman were living in a small house in Mooreland a few miles east of Woodward. They were in their 60s in 1947. The story we all heard as kids was that a young neighbor banged on their door as the storm was coming, in a panic and carrying her young child. Neither house had a basement apparently, so Del flipped over the Carmans’ heavy sofa and the four of them rode out the storm underneath it. I’ve always wondered how many homes in Woodward lacked basements — seems like a pretty important home feature to have in Oklahoma and Kansas!

As a youngster, I was in the Terry Theater with a teenage neighbor. As described the noise was horrific, the lights went out and believing the walls would collapse, we got under the seats. I was told the theater manager realized what was happening and locked the doors so no one would leave during the epicenter, which was suddenly quiet until the other side of the funnel hit with roar. Breaking glass and debris pounded the building. It was lucky as the movie wasn’t quite over so patrons were still safe inside. It was a confusing shock to leave the building. My friend and I began a terrifying walk home, a number of blocks away, which required crossing the RR tracks. Electrical lines lay everywhere We were not aware of the heroic action at the power house probably saving us in our determination to get home through that maze.

While our house had no walls, my mother and sister were saved by a visiting friend who had them lie down by the couch. The roof came down on the couch and floor leaving them unharmed in the space formed.

We spent the night in the Baker Hotel. It was a surreal scene with injured folks coming and going walking over broken glass and debris in the lobby. My little sister wrapped in a wet blanket.

While the Red Cross seems to gotten much praise, actually the first help came from a religious group who arrived early on providing help and food.

My grandparents farm was about 5 miles from Fargo. They lost the roof of the house and their large barn collapsed. Several days after the storm, I went to stay with them. Anxiety continued when strong winds blew, one time lifting the intact barn roof from the ground and folding it back. It was a memorable time.

Thank you for sharing your story, Ginna! That must have been a truly terrifying experience, especially being so young. I’m glad that your family survived, it sounds like they got very lucky indeed.

My mother-in-law Esther Deal Livengood was the telephone operator in Shattuck calling Woodward to see if they were alright. She told me how they relayed calls all night long, people calling from all over asking about loved ones and if more help was needed. My aunts house has behind the Woodward hospital, it was a big two story with bedrooms upstairs the hospital brought patients over that were not serious and they stayed in her bedrooms. Hospital also were asking all the neighbors around for sheets and towels. That part of town wasn’t hit as bad as the west/north areas.

We lived north of Mooreland, I was three yrs old at the time, neighbors stopped by and told us Woodward was hit bad by tornado. My parents, and myself drove the back roads to Woodward to find my grandmother and another aunt. There house was west of town (later the drive-in theater stood where my grandmothers house was) we found them at my aunts house safe and un-injured.

Thank you for this artical , My Mother lived on &th or 7th St. across from the funeral home. My Dad was at work. , my Mother was pregnant with me so she was on her own that night with my brother. I was born 19 days later. She talked about how they carried bodies into the funeral home all night. She told me alot of stories thur the years.

My mother, Crystal Laura Chance, and her family survived the storm by having gone to the show downtown that day. Their home was gone when they walked the 2 miles back to it.

When the tornado slammed into our house my mother and I were cleaning paint spots from the floor of my freshly painted bedroom. The windows blew in, the lights went out, and a hailstorm of aluminum beer barrels and bricks from the storage area of the wholesale beer distributor’s storage yard across the street began to slam the side of the house. Mother screamed, “It’s a cyclone! Quick, to the basement!” But so many bricks were hurtling through the passage way to the basement we could not go down, so we sat down on the couch and prayed.

Fortunately, our house was not destroyed like most of the others on our block. Everyone always said it was because when my dad and his “jackleg” helper built it in 1945 they had put so many unnecessary nails in it that the roof would not blow off. Later we found it had been raised one-quarter inch. Mother and I nailed blankets on the windows to keep the rain out and then walked two blocks north to my Aunt and Uncle’s home to check on them.

Half of their roof was gone, and my Uncle had not yet arrived from downtown where he had been managing his father-in-law’s hotel. We pushed the furniture from the front of the house back under the half-roof to keep it from the rain, my uncle Raymond arrived to find all of us (Aunt Emma, cousin Linda, cousin Charles, my mother, and me) okay and returned to town to attend to the hotel and its guests. Pretty soon another Uncle, Hurley Newcomb, arrived to take us all to his undamaged home at the corner of 8th Street and Oak. By then it was near midnight and the night sky was red with fires from all over the city.

On the way over there we passed a large grocery store where looters were ransacking the shelves and drove to the hospital where dead, dying, and injured were lying on the front lawn lined up like logs or cordwood. After some time there he took us to his home, where we children were put to bed. Sometime during the night my father arrived from Alva, Oklahoma, sixty miles away, where he had been working. When he found we were safe he went back out to help others with living and dead. Among the dead I was to learn were adults and children that I knew.

The tornado brought the school year to an end, resuming in the fall in the basements of churches and other public buildings. It threw children from four various neighborhood schools together for the first time, forging new friendships that were made under the bond of a dangerous and frightening experience. My friends from Woodward still talk about the tornado when we get together. Someone will always start the conversation saying, “Where were you when the tornado hit?”

I had relatives living in this and all around the surrounding area. Still do! I have heard stories but never seen this many pictures or read this type of verbalization by people who lived through it or, knew people who did. As I read this I didn’t realize tears were rolling down my face. I was thinking about being with my Grandparents when another tornado hit Woodward. But, nothing like this one. We lost the roof off the house but found it a few blocks down in someone’s front yard. Our metal lawn furniture was up a small incline two houses away. But, fortunately we didn’t loose family or animals.

The strangest thing about this one was something I’ll never forget. My Grandmother and I were alone at their house one afternoon when my Grandfather called telling us to take cover NOW!! He said “Do not go to the cellar. You don’t have time!!” My Grandmother came running around the corner from the kitchen. The phone receiver was dangling down the wall where she had dropped it! She grabbed me off a vanity stool and shoved me under the bed, quickly scooting under behind me. I remember her holding me so tight I thought I couldn’t breath. But, as young as I was I knew not to say a word or move a muscle. After what seemed to be an eternity the heat rolled into the house like a blast furnace. Both of us were dripping wet with sweat from the heat and intense fear. Finally, she let go of me telling me to stay still, she would be right back. I remember crying and begging her not to go as I was terrified something might happen to her!

After what seemed like an eternity she knelt beside the bed touching my arm softly pulling me from my hot prison. My skin squeaked on the hardwood floor as she drug my wet body across it. I was so surprised when I stood up seeing the bedroom in perfect order. Even the bright red lipstick I was earlier liberally adorning my lips with was exactly where I dropped it on the lower level of a knee hole vanity. I spent hours in front of the mirror at that dresser applying make-up, trying on jewelry while living in a make believe world. Only children have very active imaginations!

But, I really danced a jig when I spotted a $5 dollar bill poking out my little purse. It still sat on top of the vanity where I left it it when my Grandpa handed it to me on his way out the door with a kiss on my forehead. Suddenly I ran to the phone to call him but, it was dead. Then I realized it was really light in the house. As I looked up I couldn’t figure out why I could see the sun from inside.

Grandma explained the tornado took the roof off the house. Nonchalantly, she said we should walk around so we could try to find some of our things from the yard.

We found our furniture and some potted plants, a little worse for the wear two doors down. But, all the houses in our neighborhood were still standing. Eventually, we even found the roof a couple blocks away, for all the good it was. But, Lord were we lucky to not find the devastation shown in this very informative account of the 1947 tornado.

This is something that all of us should save on thumb drives for our children, grandchildren and eventually theirs. It’s important they see, first hand, what our relatives saw and had to rebuild. Most tragically how many had to begin again alone, after they buried their loved ones.

This is a valuable piece of history! Thank you so much to what ever group worked tirelessly putting this together!! God bless you for this sliver of our past many of us would never have known!

This is a very well-researched comprehensive story about the storm. Thank you so much for all your work on it. My mother was Margaret Larason who is mentioned at the beginning of the story. She was pregnant with me and my older brother Tim and Anne were with her at our farmhouse southwest of Fargo when the tornado hit. I’ve been hearing stories about it all my life.

REPLY

Anita Apple Valentyne (McCartor)

MARCH 23, 2016 @ 8:25 PM

I had relatives living in this and all around the surrounding area. Still do! I have heard stories but never seen this many pictures or read this type of verbalization by people who lived through it or, knew people who did. As I read this I didn’t realize tears were rolling down my face. I was thinking about being with my Grandparents when another tornado hit Woodward. But, nothing like this one. We lost the roof off the house but found it a few blocks down in someone’s front yard. Our metal lawn furniture was up a small incline two houses away. But, fortunately we didn’t loose family or animals.

The strangest thing about this one was something I’ll never forget. My Grandmother and I were alone at their house one afternoon when my Grandfather called telling us to take cover NOW!! He said “Do not go to the cellar. You don’t have time!!” My Grandmother came running around the corner from the kitchen. The phone receiver was dangling down the wall where she had dropped it! She grabbed me off a vanity stool and shoved me under the bed, quickly scooting under behind me. I remember her holding me so tight I thought I couldn’t breath. But, as young as I was I knew not to say a word or move a muscle. After what seemed to be an eternity the heat rolled into the house like a blast furnace. Both of us were dripping wet with sweat from the heat and intense fear. Finally, she let go of me telling me to stay still, she would be right back. I remember crying and begging her not to go as I was terrified something might happen to her!

After what seemed like an eternity she knelt beside the bed touching my arm softly pulling me from my hot prison. My skin squeaked on the hardwood floor as she drug my wet body across it. I was so surprised when I stood up seeing the bedroom in perfect order. Even the bright red lipstick I was earlier liberally adorning my lips with was exactly where I dropped it on the lower level of a knee hole vanity. I spent hours in front of the mirror at that dresser applying make-up, trying on jewelry while living in a make believe world. Only children have very active imaginations!