[Click photos to view larger versions.]

Deep in the Ozark Mountains, in places scarcely changed through nine decades, there are legends of a monster. Though few, if any, still live to tell the tale first-hand, the tradition persists, straddling the line between fact and myth. In the Shawnee Hills of Southern Illinois, too, old-timers pass on the legend. Indeed, across three states and more than 200 miles, folks of a certain generation recall harrowing accounts by those who witnessed death drop from the sapphire sky one balmy pre-spring afternoon in 1925. Over three and a half hours, the Great Tri-State Tornado roared through the southern portions of Missouri, Illinois and Indiana, wiping town after town off the map as it ripped through forests and farmlands, over peaks and hollows, and across the mighty Mississippi River at speeds sometimes exceeding 70 mph. When the greatest tornado disaster in recorded history finally came to an end some 219 miles later, 695 people laid dead and more than a dozen towns and hundreds of farmsteads were left in splinters.

The morning sky was odd, choking the sun out with blankets of low, leaden clouds. The ground was soft and spongy from the pitter-patter of rain that had broken out just before dawn, and although the skies had begun clearing up as the noon hour approached, intuition told 49-year-old Samuel Flowers that more was to come. As with most other residents in the hills and valleys north of Ellington, Mo., Sam had developed a keen sense for the weather through decades of working the land. Despite the dreary morning, a steady south-southeast wind had ushered in unseasonably balmy temperatures. The whites and pale pinks of wildflowers had already begun to sprout up across the rolling, muted brown fields, and the sun sparkling through mostly cloudless skies created the distinct impression that a beautiful spring day was in store for the Mid-Mississippi and Ohio Valleys. But Sam knew better. Just before 1:00pm, rumbles of thunder rolling in from the southwest confirmed his suspicion — a storm was coming.

What Sam Flowers couldn’t know as he urged his horse toward home was that a broad area of low pressure had descended from Canada several days earlier and begun to deepen in the lee of the Rocky Mountains. After dropping southeast into the Central Plains the previous day, the fully-developed cyclone began pulling in vast quantities of warm, moisture-laden air on its eastern flank as it accelerated toward the Ozarks. Directly to the east of the surface low, a warm front pushed north across the Ohio River and into southern Illinois. A dryline extended to the south, with a weak cold front trailing to the southwest. Higher in the atmosphere, a fast-moving shortwave trough traversed the Rockies and began to dig into the Central and Southern Plains and take on a slight negative tilt. At the same time, a strong jet streak nosed into the Ozarks from the southwest. Warm, dry air in the mid-levels spread east across the Mississippi, setting up a strong capping inversion.

A composite surface map from 18z (12pm), about an hour before the tornado formed. Pressure, wind observations, temperature, dew points and approximate locations of fronts are shown. The track of the tornado is indicated by the white line east of the low. As the low progressed during the afternoon and evening, it followed roughly along the pressure trough to the northeast (black dashed line).

Thunderstorm activity began just after midnight as several cells erupted to produce large hail across eastern Oklahoma and Kansas, as well as a brief tornado that damaged several structures west of Coffeyville. Light rain broke out shortly before daybreak across much of Missouri, Illinois and the southern half of Indiana, creating a pool of rain-cooled air to the north of the advancing warm front. By midday, the surging warm front had brought temperatures into the middle and upper 60s. Plumes of unstable air near the surface began to rise into the atmosphere, eventually bumping into the warm, dry cap. Just minutes after noon, near the triple point where the warm front, cold front and dryline merged in south-central Missouri, a lone thunderhead burst into the sky. Whipped and twisted by the strong wind shear throughout the atmosphere, the thunderstorm quickly became supercellular as it raced northeastward.

Shortly before 1:00pm, a low, ragged cloud descended over the forests northwest of Ellington in Reynolds County, Mo. As Sam Flowers spurred his horse on toward his farmhouse, a low rumble grew on the horizon. The sky to the southwest had grown dark and menacing, and a warm wind had begun whistling through the tall oaks and shortleaf pines. The horse, affectionately named Babe, broke into a full gallop as Sam grasped desperately at his saddle horn. Large hailstones pummeled the earth and left divots in the soft grass. Within seconds, the distant rumble bore down with a tremendous roar. What happened next is not clear, but a short while later Babe returned to the Flowers farm without her rider. Sam was found several hours later some distance from the road, his head smashed beneath a tree. The most devastating tornado in United States history had claimed its first victim.

• • •

In the small mining village of Annapolis, most residents had just returned to work from their lunch breaks. Just east of town in the tiny outpost of Leadanna — named after the ubiquitous mineral harvested throughout the area — many of the men had returned to toil in the mines deep below ground. Children had just been called in from recess at Annapolis School and were streaming back into the small, two-story brick structure. The first indication of trouble came from residents just outside of town, who were afforded a relatively clear view of the rolling hills to the west. The skies in that direction had taken on a strange, bruised appearance, the type that often preceded the strong storms that lashed the region at least a few times each spring. Suddenly, a murky figure emerged atop the nearest hill. More resembling a great, billowing fog than a funnel cloud, the tornado ripped through the valley and engulfed the tiny town and its residents in seconds.

The children at Annapolis School became frightened by the rapidly deteriorating weather. The sun disappeared in a torrent of rain and hail. Wind shook the trees outside the schoolhouse windows. The teacher, fighting back her own trepidation, gathered the children around her desk in an attempt to comfort them. The cries of the 25 students were drowned out by the furious roar as the tornado blasted through, taking just seconds to reduce much of the brick schoolhouse to rubble. Miraculously, all of the children survived with only minor injuries. The mines in Leadanna also sustained heavy damage. Offices, medical buildings, grocers and other structures were destroyed, and much of the mining machinery was ripped up and mangled beyond repair.

As the school children and the miners rushed back to town to check on their families, they were greeted with a scene of total devastation. Residents wandered in a daze. Children cried for their parents. Survivors climbed out from mountains of broken timber and other debris. Those who witnessed the aftermath later recounted that, of the town’s approximately 400 buildings, more than 90 percent were damaged or destroyed. The tornado was likely only of moderate intensity as it struck the town, but it left a trail of damage perhaps a mile wide. Four people were killed in all, two in Annapolis and two in Leadanna who were caught above ground and struck by flying timbers. A marriage certificate for Nell and Osro Kelly, the latter of whom was among the tornado’s victims, was later found 77 miles away in Murphysboro. The local lead industry was nearly ruined. The mine continued to operate in limited capacity until the 1940s, but it never again matched the production it had achieved before the tornado.

A general store in downtown Annapolis was left splintered, scattered among the ruins of hundreds of other homes and businesses. Red Cross tents for survivors can be seen in the background on the left.

Because of its resemblance to the low hills of southwest Germany’s Black Forest region, the Ozark hills of Iron, Madison and western Bollinger Counties were populated largely by German immigrants. Most had become farmers, and the grapes that many of them grew were among the finest in the United States for producing high-quality wine. The terrain was rough, forested and sparsely populated, leading to a number of gaps in the documented track of the tornado. It’s not clear whether any of the gaps represents an actual break in the tornado path, but what is clear is that, where the swirling vortex did strike, it had lost none of its violent intensity. Dozens of homes were destroyed across about 50 miles of Iron, Madison and Bollinger Counties, and 32 children were injured when two schools were destroyed in Bollinger County. About ten miles west of Sedgewickville in northwestern Bollinger County, grass and several inches of soil were reportedly scoured from the ground near the home of Emily Shrum, which was completely leveled.

The home of Emily Shrum, which was located on the south side of the mile-wide damage path. Ground scouring was noted nearby.

After claiming several victims in Bollinger County, the tornado struck western Perry County as a “double funnel.” The massive tornado churned through the tiny village of Biehle, joined by a satellite vortex that traveled on a nearly parallel track for about three miles. Between the two tornadoes, dozens of homes were destroyed and four of Biehle’s residents were killed. To the northeast, in the unincorporated community of Ridge, the Ridge Parochial School was squarely in the path of the violent twister. The wind began driving sheets of rain against the roof, and soon it blew the thick wooden door open. The teacher, determined not to let a little storm ruin her classes, ordered the students to hold the door closed against the storm. As the tornado bore down, it ripped the school from its foundation and sent it hurtling several yards into a nearby hillside. Miraculously, despite the complete destruction of the structure and dozens of serious injuries, none of the school’s occupants were killed.

As the tornado tore across the more populous rolling hills and lowlands of Perry County and toward the banks of the Mississippi River, the tornado again began to claim lives. About four miles northeast of Frohna, the very large, well-built home of Perry County District Judge Claus Stueve was completely demolished. He sustained various injuries, while his wife and a houseguest were killed. Just to the west, the home and barn of Theo Holschen were obliterated and three family members were seriously injured. In total, the tornado killed at least thirteen Missourians and left a path of devastation at least 85 miles long — perhaps up to 100 miles — and at times more than a mile wide. This alone would have been an impressive feat, but far worse was yet to come. The next 45 minutes were to bring perhaps the most horrifying display of sustained tornadic violence in recorded history.

• • •

On the Illinois side of the Mississippi River, towering riverside bluffs skirt the southern extent of a broad, flat floodplain. Fertile farmland spreads like a patchwork quilt across the plain, broken only by a spiderweb of rail lines which converge on the little river town of Gorham. In 1925, Gorham was a vital stop along the Missouri Pacific and Illinois Central railroads, where coal from across the region was funneled through the rail yards on the town’s south side on its way to the larger markets from St. Louis to Texas. The influx of rail traffic brought welcome business to sleepy Gorham, as general stores, restaurants, hotels and other amenities popped up to serve the railroad crews when they stopped to refuel and cool the engines. The permanent population was between 500 and 700, but Gorham was a town on the rise.

Like so many others, the first warning of the approaching catastrophe that Gorham’s residents received was a dark, menacing mass of cloud approaching from atop the bluffs southwest of town. After spending nearly an hour and a half tearing across southeastern Missouri, the tornado crossed the half-mile span of the mighty Mississippi River in seconds and barreled into Jackson County in southwest Illinois. The tornado roared across the fields west of Gorham with such tremendous force that it scoured a large patch of ground, stripping the grass from the earth and plowing up several inches of soil in a shallow gully. Trees on the outskirts of town were stripped of bark and limbs, with many ripped from the ground or snapped off. Those in Gorham had only seconds to react as the thundering black mass bore down on the town at more than 60 mph.

The tornado entered town near the rail yards, throwing boxcars and demolishing the nearby depots and office buildings. A section of train tracks was torn from the ground and some of the crossties were thrown into the rubble of surrounding buildings. A row of homes and businesses along Main Street virtually exploded in a cloud of shattered timbers and roofing. The rest of the town met the same fate, as rows of homes, apartments and other buildings were reduced to rubble in a matter of seconds. One child was thrown nearly a quarter of a mile into the ruins of a business. In the words of a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

“All morning, before the tornado, it had rained. The day was dark and gloomy. The air was heavy. There was no wind. Then the drizzle increased. The heavens seemed to open, pouring down a flood. The day grew black…

Then the air was filled with 10,000 things. Boards, poles, cans, garments, stoves, whole sides of the little frame houses, in some cases the houses themselves, were picked up and smashed to earth. And living beings, too. A baby was blown from its mother’s arms. A cow, picked up by the wind, was hurled into the village restaurant.”

Near the center of town, a large building housed both the grade school and high school. The tornado tore off the roof and battered the thick walls, collapsing them in on the children and teachers sheltering inside. Thirteen year old Margaret Brown, daughter of school superintendent Lewis Watson Brown, was killed when she was reportedly “cut in two” by a large brass bell that had fallen from the peak of the roof. Brown’s wife, Della, was also killed when their home was swept away. Two other families also suffered tremendous losses. Seventy-three year old Mary Moschenrosen and three of her adult children were killed by the swirling vortex, as were four members of the Needham family. A pair of pants containing scraps of paper bearing the name Moschenrosen were subsequently found nearly 20 miles to the northeast of Gorham. A husband and wife were thrown some distance from their home, shards of timber impaled through the wife’s abdomen.

By the time the fury of the wind had passed, Gorham had become the first, but unfortunately not the last, to bear a grim distinction: 100 percent destruction. Nearly every single structure in town was damaged or destroyed, the majority of them reduced to splinters and scattered to the wind. In the chaos that followed, as would be the case in many areas, no accurate list of the dead was kept. As best as can be discerned through newspaper reports and cemetery listings, between 32 and 37 of Gorham’s residents were killed and about 170 others seriously injured. Dozens of horses and cattle were also killed, and one horse from near Gorham was allegedly found at Sand Ridge, nearly two and a half miles to the northeast. In the span of minutes, thriving Gorham had been reduced to an utter wreck from which it would never fully recover.

Complete devastation near the center of Gorham. Note the trees or poles snapped off near ground level in the background.

• • •

If Gorham was a town on the rise, Murphysboro was what it aspired to. A modest but thriving city, Murphysboro was home to more than 15,000 people in the early part of the 20th Century. The Big Muddy River, a tributary of the Mississippi, wound its way through the western part of town. Business was booming, and much of it was centered in a relatively small, densely populated industrial sector in the northwest quadrant of the city. The industrial sector was the lifeblood of the growing city, providing jobs and rapid economic growth that had made Murphysboro a fixture in southern Illinois. The city also held appeal for some because of its nonchalant attitude toward prohibition. While neighboring towns cracked down on illegal production facilities and speakeasies, alcohol was rarely difficult to find in Murphysboro.

A view of Murphysboro before the tornado, taken facing northwest from the top of the Brown Shoe Company Water Tower.

At 2:34pm, less than eight minutes after laying waste to the town of Gorham, the monstrous storm thundered into the southwest edge of Murphysboro. After leveling a number of homes outside of town, the tornado crossed the Big Muddy River and almost immediately began destroying homes along Clay and Dewey Streets. At Lincoln School, where children had recently been called in from recess, the windows shattered almost simultaneously as the outer fringe of the circulation passed to the northwest. A wall on the second floor collapsed and crumbled outward. Thanks to the quick thinking of the school’s officials, however, students were moved to the northwest corner of the building and there were no injuries. Just to the north and closer to the center of the path, enormous hardwood trees were snapped just feet above ground level. Some were stripped bare, or uprooted and thrown hundreds of feet.

As the tornado approached the intersection of Walnut and 20th Streets, the damage became catastrophic. Several rows of homes were completely demolished with some partially swept away, and trees in the area were debarked and denuded. Six members of the Miller family, including children of one, three, five and nine years old, were killed at one home along Walnut Street when their home was completely flattened. Along Logan Street to north, 17 children were killed when the Longfellow School partially collapsed from the force of the wind. The Mobile and Ohio Railroad shop and roundhouse, about a block to the east of the school, was severely damaged. Some workers survived by taking shelter under the heavy machinery and structures, but 35 were killed by building collapses and flying debris. A number of locomotives were rolled or thrown from the tracks, causing further death and destruction.

The partially collapsed Longfellow School, where 17 children were killed. This photo became one of the iconic images of the devastation wrought by the Tri-State Tornado.

At 15th and Logan, a funeral was in progress in the basement of the First Baptist Church. Construction had been in progress on the church building and was nearing completion at the time. According to the Reverend H. T. Abbott, he had just begun reciting the popular funeral sermon “Yea, though ye walk in the valley and the shadow..” when a “thunderous noise” overtook the church and collapsed a large section of the sturdy building. Being assembled in the basement, there were no injuries among the funeral crowd. Immediately upon exiting the rubble of the building, however, the funeral-goers was confronted with a sight of utter devastation. About a block to the northeast, the Logan School had suffered heavy damage. Many in the crowd sprinted to the school to aid in rescuing children and staff from the rubble. Nine children were killed at the Logan School.

This photo was taken near the location of the Baptist Church and approximates the view the funeral crowd would have seen upon emerging. The Logan School can be seen in the background.

The tornado continued northeast, chewing through the residential heart of the city. Hundreds of homes were completely leveled, crushing or throwing those inside. Many families suffered multiple casualties. When a horse and buggy was caught in the tornado near Manning Street, the horse was found more than half a mile away. The buggy was never found. In all, at least 120 city blocks were completely demolished by the tornado’s unbridled fury. Once the tornado had passed, another disaster began to unfold. Coal-burning stoves throughout the city, toppled or thrown by the wind, ignited fires that quickly turned the shattered piles of rubble into a great inferno. Many of those who were fortunate enough to survive the initial onslaught burned to death as the fire erupted out of control. Eighteen people were killed by fire at the Blue Front Hotel after becoming trapped in the basement.

A view of the devastation along 15th Street. Flames and billowing smoke can be seen engulfing the piles of debris in the background.

A panorama view of the devastation in Murphysboro. The combination of tornado and fire reduced virtually the entire west and north sides of town to rubble.

By the time the fires had been extinguished, Murphysboro was in ruin. Two hundred and thirty-four people laid dead, the largest death toll in a single city in United States history. More than 600 others were seriously injured. According to contemporary reports in local newspapers, various receipts, checks, certificates and other paper items from Murphysboro were found as far away as Bloomington, Ind., 180 miles to the northeast. The industrial sector of the city was destroyed, as was the railroad and many of the businesses in town. The tornado had torn a complex path of destruction through the city nearly a mile wide. In some cases moderately damaged homes stood across the street from areas of total devastation, suggesting the tornado had a multivortex structure. A number of homes well to the south of the primary path also suffered moderate damage, apparently caused by intense inflow or rear-flank downdraft winds associated with the supercell. The tornado had already tracked more than 110 miles and claimed nearly 300 lives, yet a full two hours of death and destruction still lay ahead.

Complete devastation in the path of the tornado in the foreground. In the background are homes on the south side of the city likely damaged by intense inflow or RFD winds.

An aerial view looking southeast from north of Walnut Street. In the foreground is the southern edge of the tornado path. The previous photo was likely taken somewhere along the left edge of this image.

• • •

After exiting Murphysboro, the tornado tore across the countryside with undiminished ferocity. The Will School, about two miles northeast of town, was razed to its foundation. A few miles beyond the school, Electra Beasley and her son Richard were killed when their farmstead was destroyed and swept away. The tornado narrowed slightly as it approached the west side of De Soto, but its destructive power was on full display. As in Murphysboro, whole sections of homes were completely flattened and swept away. Trees were debarked, denuded and snapped, leading one resident to remark that “not a tree was left standing taller than a man’s knee” in the main damage path. One couple was killed when their car was thrown 50 yards from the main highway. Several other vehicles were thrown or rolled and left completely mangled, and wind rowing of debris was evident in several areas.

At the Albon State Bank, many residents took shelter in the reinforced concrete vault. The bank and surrounding buildings were largely destroyed despite being on the southern edge of the worst damage, but those who sheltered inside survived. Many others in town were not so lucky, as 36 lives were lost in the devastation of downtown De Soto. An even greater tragedy was looming, however. At the De Soto School just northeast of downtown, the threatening skies prompted officials to rush the children in from recess. The girls were quickly ushered back to their desks, while the boys were assigned to close the many windows along the outside walls of their classrooms. Moments later, the windows exploded in a hail of shattered glass and debris.

A panorama taken from a rooftop near the current location of Route 149 and facing approximately southeast. At center is the Albon State Bank vault.

Battered by the extreme wind, the top floor and a number of walls collapsed. Tons of bricks crumbled and fell atop the schoolchildren and faculty inside, crushing nearly 30 of the students to death and severely injuring many more. Because they were along the exterior walls closing windows, the majority of the victims were boys. Four more children were caught outside when the tornado struck. Three young girls were using the school’s outhouses when they were picked up and thrown nearly two-tenths of a mile across the railroad tracks. Another girl was cut in half when she was picked up by the tornado and thrown some distance into a steel lightpost. In all, 33 children were killed at the De Soto School, the greatest tornado-related death toll ever recorded at a school. After the bodies were pulled from the rubble, so many of the children’s parents were injured or killed that the principal was tasked with identifying many of the students. All told, 69 people would die in De Soto.

A man searches amid the destruction of homes in the northeast section of De Soto. The ruined school can be seen in the background.

• • •

Four miles northeast of De Soto, the community of Hurst and the mining camp at Bush experienced significant damage. Just southeast of Royalton, the Royalton-Colp Road bridge and a nearby swinging bridge were thrown from their pillars. Dozens of people were killed when about a dozen homes were damaged or destroyed in the rural areas between Royalton and Plumfield. In the small village of Plumfield, the local school was obliterated by the mile-wide tornado. Students Barbara Hamon and Anna Johnson were killed. Sarah Davis, who had been attending a meeting at the nearby church, ran to the school to comfort the children and was killed. Sarah’s husband Jefferson was killed moments later when the Davis farm was demolished and he was thrown hundreds of yards into a nearby field.

At the Big Muddy River, a large section (right) of the heavy iron Royalton-Colp Road bridge was torn from its pillars and thrown into the river.

About 15 miles northeast of De Soto, the town of West Frankfort sprawled in a west-to-east direction. The Orient Mine #2, recently established on the northwest side of town, had brought an influx of population and growth. A new subdivision, complete with brand new homes and streets, sprang up to house miners and their families. As the massive vortex departed Plumfield and continued its northeastward path of destruction, the Orient Mine and its associated subdivision were squarely in its sights. On the western edge of town, two school buildings were torn from their foundations and destroyed. The newly-built homes in the area were no match for the ferocious wind, and most were obliterated. Large church buildings were also flattened, and vehicles were thrown several blocks. The home of Clyde Reed was reduced to splinters, killing a young child and injuring his wife and several other children.

Many of West Frankfort’s men were several hundred feet beneath the surface in the Orient and Caldwell mines when the tornado struck. An intense suction caused the air to rush from the mine, accompanied by a terrific roaring and shaking. One man was killed when he was caught above-ground in one of the mine buildings. When the miners emerged, they were greeted with a heartbreaking scene of abject devastation. Nearly every home in sight, most belonging to the miners and their families, was utterly decimated. In the words of one person, “everything in view was brought level to the ground.” Screams of desperation issued from heaps of rubble. Those who were fortunate enough to survive without being trapped wandered the streets in a daze, most of them battered and bloody. Miners frantically clawed through the debris in search of their wives and children. Amid the remains of one home, a mother was found with her chest torn open by flying debris, her infant daughter still trying to nurse.

This aerial view, taken near the Orient Mines, is similar to the scene the miners would have witnessed upon emerging from underground.

The destruction was no less complete at the mines, where offices, manufacturing plants, equipment and other structures were completely wrecked. A mine tipple weighing several tons was pushed over and rolled some distance, and a large water tower was destroyed. A line of boxcars was thrown from the tracks just south of the mines. The nearby home of Elisha and Emma Clark, out of which the couple operated a small grocery store, was completely leveled. Elisha was blown some distance from the home and into a pile of uprooted apple trees and suffered several injuries. His wife Emma and daughter Lelia were both killed. Continuing northeastward, the tornado destroyed the Chicago & Eastern Illinois railroad roundhouse and several of the buildings at the Peabody Mine #19. Several loaded coal cars were blown from the tracks just east of Peabody #19. To the north, a bridge was blown from its piers along the C. E. I. railroad and 300 feet of track was torn from the ground. A small village of homes, stores and other buildings was destroyed to the northeast near the Peabody Mine #18, where 52 people were killed.

In total, despite only impacting the north and west sides of the town, the tornado claimed 132 lives in and around West Frankfort. More than 500 homes, three churches, two schools and numerous other buildings were demolished. Because most of the town’s men worked in the mines, the majority of the fatalities were women and children. Several eyewitnesses reported that bodies from West Frankfort were later found more than a mile and a half from their original locations. According to conflicting reports, either seven or eleven members of the Karnes family were killed, including Mrs. Oscar Karnes and four of her children who were thrown into a lake near the Peabody Mine #18. Just north of Crawford Cemetery, James Kerley’s home was razed to the ground and swept away. James survived, but Ettie Kerley and her children, Homer, Otto and Bertha, were killed.

Just six miles to the northeast, the scene of death and destruction repeated itself in the town of Parrish. Twenty lives were lost in the small mining village as virtually every structure was leveled. Half a mile east of Parrish, the home of Randell Smith was obliterated. Randell and a relative, William Biggs, survived the tornado by clinging to a small grove of trees until the storm passed. Randell was blinded and his wife was badly injured, and their seven year old daughter Hattie was killed. Several dozen additional homes were destroyed as the tornado tore a mile-wide path toward the Hamilton County border. Trees along Ewing Creek were reportedly debarked and shredded, and several horses and a buggy near the Willow Branch School were “blown away.” Between Gorham and Parrish, the tornado carved a path of devastation through 47 miles of southern Illinois. In just 40 minutes, the tornado killed at least 540 people, injured nearly 1,500 and produced $11.8 million dollars of damage — just over a billion dollars in 2000 USD.

William Biggs demonstrates how he and Randell Smith survived when they were blown from the Smith farmhouse.

• • •

By 1925, the mining industry that defined much of southwestern Illinois had lost its grip in Hamilton and White Counties. Though a handful of small mines still dotted the pancake-flat land, farming had grown to become the driving force of the local economy. The area was rural, but hardly unpopulated. Farmhouses were scattered along nearly every road throughout both counties. The tornado thundered into Hamilton County shortly after 3:10pm, and almost immediately continued its path of destruction. Ollie Flannigan’s home and barn were destroyed, killing her and her brother Sam. A photograph from the Flannigan home was later found in Bone Gap, Illinois, 50 miles to the northeast. Just to the east, Columbus Hicks and his daughter-in-law Martha were killed when the family farmhouse was swept away. Lonnie Smith’s farmstead was also obliterated, killing four in the Smith family and severely injuring another. A home was destroyed to the southeast of the main path by a brief but strong satellite tornado.

The destroyed home of Lonnie Smith, where four members of the Smith family were killed and two others were seriously injured.

In the small community of Olga, several homes were damaged or destroyed. A church was moderately damaged and the Olga School was blown off its foundation. Numerous trees were heavily damaged just southwest of town. To the northeast at the Parkers Prairie School, one student was thrown into a stand of trees and killed and Wesley Cluck, who had arrived at the school to pick up his children, was also thrown by the tornado and killed. A short distance east of the school, Chalon Cheek had gone south to a neighbor’s home when they noticed billowing black clouds in the distance. Chalon watched from the neighbor’s porch as the violently rotating wedge tornado bore down on his property and ripped his home from its foundation. His wife, stepdaughter and brother were in the home at the time, and all three were killed. Immediately east of the Cheek family home, the Lick Creek Bridge was lifted and thrown 300 feet into the creek. A patch of young trees and shrubs were stripped and uprooted, and grass was scoured from the ground on the Lawrence Dolan farm. At least a dozen people were killed nearby.

The tornado continued an unbroken path of destruction into White County. Just southeast of the town of Enfield, the Trousdale School collapsed on the students inside and then was swept away. Reportedly all but one of the students was seriously injured. Throughout the Enfield area, dozens of homes were destroyed and swept away. Fifteen people were killed and several dozen others injured. A thick, 18-acre patch of woods near the C. S. Conger farm was almost entirely snapped and uprooted. Just to the north of the damage path there were reports of hail as large as three to four inches, occasionally so heavy that it covered the ground. Several eyewitnesses in this area described the tornado as a “rolling black mass,” swirling with thousands of pieces of debris. In some cases the approach of the tornado was preceded by pieces of debris raining from the sky.

At the Newman School, several miles northwest of Carmi, teacher Jasper Mossberger noticed the skies had become dark and menacing. Sheets of rain spattered the windows, and a stiff wind rattled the door and threatened to blow it open. The students huddled around their teacher to hold the door against the approaching storm. Within moments, the roaring wind shattered the flimsy building and reduced it to rubble. Nearly every child was injured, some critically, but all survived. Teacher Jasper Mossberger initially survived, but died weeks later from complications of his injuries. Next door to the school, a mother and small child were killed when their home was destroyed and they were thrown into a ditch several hundred yards away. At this point, the tornado may have been more than 1.3 miles wide.

Continuing ceaselessly to the northeast, the tornado chewed up dozens of homes, schools and churches scattered throughout central and eastern White County. Just southwest of Crossville, several cars were blown from the state road and train cars were blown off the tracks nearby. The Graves School was completely decimated and several students were thrown from the wreckage. As in Murphysboro and elsewhere, wrecked homes and their occupants occasionally faced further danger from tipped-over coal stoves that ignited the shattered piles of wood and debris. The village of Crossville itself was spared, but those immediately to the south were not so lucky. The number of deaths varies, but several homes were completely destroyed in the area. In total, 65 residents of Hamilton and White counties were killed, including more than 30 farm owners. The exceptional intensity, forward speed and unusually large and occasionally obscured appearance conspired to catch even the most weather-wise farmers off-guard. The monstrous vortex had already done the worst of its terrible work, but still more was to come upon crossing the Wabash River into Indiana.

• • •

Just before 4:00pm, the twister raced across the Wabash River, destroying homes on both banks, and bore down on the little village of Griffin. Measuring only half a mile north to south, Griffin was no match for the massive, mile-wide tempest. A number of farm homes just south and west of town were immediately swept clean. At Bethel Township School, the school’s only bus had left to deliver half the children on the west part of town before circling back to pick up the others. As the bus made its first stop to drop off the Vanway children — Harry, Ellen, Hellen and Evelyn — bus driver Chick Oller noticed objects of various sizes falling from the sky. Within seconds the massive funnel barrelled across Matz Road, tossing and tumbling the bus and tearing at the sheet metal exterior. When the bus came to rest in a nearby field, the mangled frame rested atop two children who had been crushed beneath it. Harry and Hellen Vanway were caught in the violent storm of debris just outside their home. Harry was struck in the head by a flying timber and killed instantly, while Hellen was gravely injured and died within hours.

In Griffin proper, the destruction was complete. As in Gorham, 100 percent of the structures in town were damaged or destroyed, most of them leveled. Eyewitnesses described a very large, multivortex tornado that produced several funnels that “moved around and then came together.” Several stores, a gas station, a theater, an electric light plant and several churches were also destroyed. The large brick Bethel Township School was heavily damaged but not destroyed. Many of the structures that escaped heavy damage from the initial strike of the tornado were destroyed when one subvortex reportedly wrapped around the southwest flank and raked the eastern and central portions of the town. Dark, fine silt and mud, picked up from the Wabash River as the tornado crossed it, was plastered to both people and homes. Several poles were snapped just above ground level, and the railroad tracks were once again pulled from the ground and bent at odd angles. In the few seconds it took the tornado to plow through the three-block width of Griffin, a full 60% of its 400 citizens were counted among the casualties, including dozens of fatalities.

The rubble of the business district, including Trinity Baptist Church. Only the steps (left center) remain standing. A relief train can be seen in the background.

After devastating Griffin, the tornado continued on across northern Posey and southwestern Gibson counties, destroying rural homes in much the same way as it had done in Hamilton and White counties earlier. It clipped the northwest edge of Owensville, destroying the Christian Church and several homes. At one home, William King and his son Walter were killed, as were their wives Elizabeth and Lora. Many trees were stripped and mangled at an apple orchard just north of Owensville. A forest nearby also suffered heavy damage. Dozens of other homes and barns were damaged or destroyed across central Gibson County as the tornado continued at a width of nearly one mile. Several vehicles were thrown or rolled great distances from the road, and a locomotive and its railcars were pushed from the tracks just outside of town. Vegetation may also have been scoured from the ground in nearby rural areas.

• • •

It was 4:18pm — a full three hours after the great storm had first begun its path of apocalyptic destruction — and yet the tornado had lost none of its power when it emerged on the horizon west of Princeton, Indiana. With a population of just over 6,000 in 1925, Princeton was famed for its excellent tomato farms. The H. J. Heinz Company quickly became one of the area’s largest employers, using local tomatoes to produce its ketchup and other products in a pair of large brick buildings on the south side of town. Like so many other towns in Indiana and Illinois, Princeton also benefitted greatly from the rich coal seams atop which it sat.

On the afternoon of March 18, downtown Princeton was buzzing with activity. Like any other Wednesday, it was “Bargain Day,” when people from all around came to shop at the many stores that offered sales and raffles. At about 4:00pm, small bits of debris began to drift down from the sky like snowflakes. The western sky became bruised and menacing, the black clouds flickering with constant lightning. When the swirling funnel came into view, it was choked with debris. It had already wiped dozens of homes from the earth on its way from Owensville to Princeton, and it made quick work of the nursery building and a grove of mature fruit trees on the southwest edge of town. Many homes in the nearby McKaw Summit subdivision suffered damage from the northern edge of the tornado.

In the Baldwin Heights subdivision, immediately west of the Heinz Company’s factories, the destruction was complete. More than two dozen homes were razed to the ground. The sturdy, well-built Heinz factory and office buildings were damaged considerably but not destroyed. The storage building was swept away. Heavy iron support structures were damaged and bent at the Southern Railroad Shop, where the roundhouse and several other structures suffered major damage. Continuing through the primarily residential southern section of Princeton, the tornado left a streak of complete destruction about a quarter of a mile wide and a broader area of substantial damage just over a mile wide. Though most of downtown was spared, the destruction was massive. Much of the southern third of the town was reduced to rubble, and 45 people were killed.

A view of the Heinz factory buildings, looking northeast. Debris from the devastated Baldwin Heights subdivision is seen in the foreground.

A closeup view of the Heinz factory. Tomato baskets, signs and other debris are piled in the foreground.

At approximately 4:29pm, more than 220 miles after it began, the Great Tri-State Tornado shrunk, weakened and finally dissipated over an unplanted corn field on the Silas Merrick property, ten miles northeast of Princeton. In its wake, nearly a dozen cities and towns were left broken. Two were utterly wiped from the surface of the earth. At least 695 people were killed, over 2,000 injured, and many tens of thousands left homeless. It maintained a forward speed of well over 60 mph over three and a half hours, at times reaching a width in excess of 1.25 miles, and claimed both rural farmers and urbanites alike. The single greatest tornado event in world history left a toll, both in lives and in damages, that was nearly beyond comprehension. And yet, the day was not done. Great thunderheads were building across the Heartland and parts of the Southeast.

• • •

About 15 minutes later and 250 miles away, a small tornado cut an extremely narrow path through Colbert County in Alabama. The tornado damaged a gas station, two homes and a shop near Littleville, killing one man and injuring about a dozen. Just after 5:00pm, an imposing storm that had been brewing over western Tennessee dropped a small, ragged funnel near the community of Buck Lodge in central Sumner County. The tornado rapidly grew to nearly a quarter mile in width and the tornado claimed its first lives when Matilda and Maude Key were killed in their home. Continuing on, the tornado passed near the community of Graball.

Just to the northeast, the homes of Jim and Mary Allison and the Henry Hughes and Cleveland Hughes families sat atop a small hill. Ella Hughes, being home alone when the storm approached, became frightened when she heard a dull roar to the west-southwest. She sprinted off in the pounding rain and wind toward the Allison home a half-mile away. Moments later, as the Allison family prepared for their dinner, the violent tornado barrelled over the hill and obliterated their home. Jim and Mary Allison and all six of their children, ages 20, 16, 14, 6, 5 and 4, were killed instantly. The tornado struck with such unbridled fury that the bodies were scattered over a quarter of a mile, mangled and wrapped around debarked tree stubs. The two youngest children were “torn in sections,” and surviving relatives were unable to identify many of the remains. Ella Hughes, who had just reached the house as the storm bore down, was also killed. Tragically, her home was left almost entirely unscathed.

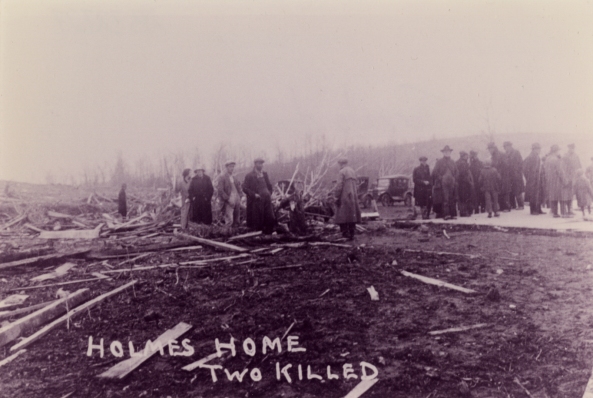

A short distance to the northeast, the home of Ella’s father-in-law Henry was swept cleanly away. Henry, his son-in-law Cleveland and his wife were killed when the home was destroyed. In a community called Angle, just south of Oak Grove, the tornado again demonstrated its frightful power. The homes of Charles Durham and his son Joe were completely leveled and swept away. Charles, his wife and their baby daughter Lorena were killed. Moments later, Joe Durham’s wife and two children were killed. Joe was away at the time and was the only member of his family to survive. Several yards away, Charles Holmes’ home was also swept cleanly from its foundation. Charles and his wife were both killed, but their two daughters survived despite serious injuries. A contemporary report from The Knoxville Journal recorded that even concrete and stone foundations were scoured from the ground and scattered by the savage wind at several locations between Keytown and Oak Grove, but there is no known photographic evidence of this.

The field near Charles and Joe Durham’s homes was littered with small bits of timber and other debris from the demolished homes.

The tornado continued its campaign of ruin in the little village of Liberty. According to one eyewitness who watched the event from a distant hill, the Liberty Presbyterian Church was torn from its foundation whole before quickly disintegrating “like a bunch of matchsticks.” A home just down the road from the church was also obliterated, but the family survived by taking shelter in a milk well. The Brown home was swept clean just to the northeast, and the entire family was killed. Wheat and grass were scoured from the ground in a field across the road, leaving nothing but a 60-yard wide, 200 yard long streak of dirt. After destroying a string of homes for several more miles, the tornado may have weakened or lifted briefly in Macon County. As it neared the Kentucky state line, however, tornado damage again became intense. The tornado destroyed several dozen homes and killed four people in the community of Holland, and killed another eight people in Beaumont before coming to an end after about 60 miles on the ground.

In central Harrison County, Indiana, yet another monster tornado dropped to the earth at about 5:15pm. After causing extensive tree damage in a narrow path, the tornado rapidly expanded to nearly a mile wide. Several farmhouses were swept cleanly away near Laconia, where two people in one family were killed. Near Elizabeth, two more people were killed when about a dozen homes were flattened and swept away. The tornado weakened and narrowed as it crossed the state line south of Louisville. At least four other tornadoes raked Tennessee and Kentucky in the next hour and a half, including one tornado that destroyed a number of homes and completely scoured the ground.

• • •

By the time the sun had set on Wednesday, March 18, 1925, at least 747 people laid dead across five states and more than 425 miles of ruin. With at least 695 fatalities, the Tri-State Tornado alone claimed a staggering 142 more lives than the next-deadliest entire year on record (553 in 2011). The tornado caused the most student fatalities in a single tornado (69) and the most deaths ever at one school (33) in De Soto. The tornado also has the record for the longest path ever recorded, though the exact length is uncertain. Beginning from the first recorded tornado damage in Shannon County, Mo. and ending with the last recorded damage northeast of Princeton, Ind., the total length is approximately 235 miles, with several gaps in damage reports that could indicate breaks in the path. There are mostly continuous damage reports from south of Fredricktown in Madison County, Mo. to the end of the accepted path about ten miles northeast of Princeton in far western Pike County, Ind. This suggests a path length of at least 174 miles, still the longest confirmable path length ever recorded.

The Great Tri-State Tornado remains an historical anomaly of terrifying proportions. Never before or since have we seen a tornado in the United States kill so many people, stay on the ground so long, travel so quickly or cause so much damage. Understandably overshadowed by the great tragedy to the north, the outbreak across Kentucky and Tennessee may well have been very significant in itself. The overwhelming devastation across the areas affected left marks that took decades to heal. Tens of thousands of people left homeless, many of them also rendered jobless, just years before the Great Depression closed its grip on the nation. Even in light of devastating tornadoes and outbreaks in recent years it’s difficult to make sense of the incredible scale of destruction. The full details of that day are likely lost to the march of time, but March 18, 1925 undoubtedly remains one of the greatest natural disasters in American history.

Such an insightful and well-written article! I truly look forward to each of your posts. Do you generally only write about major tornadoes and outbreaks or are there other factors that cause you to write certain articles as well? Keep up the fantastic job! I’m looking forward to your next post. How rare is it for a tornado to stay on the ground for that length of time?

Thank you Dean, appreciate it! I mostly just write about events I find interesting, though I don’t mind doing a particular event if people want to see it. I have a backlog of about a hundred events I’d like to get to, but with not much free time they’re pretty slow going. I’d like to do some hurricanes and maybe blizzards too, but tornadoes are most fascinating to me.

As for the path length, it’s unprecedented as far as the historical record goes. There are a few tornadoes (Woodward in 1947 being probably most notable) listed with extremely long paths, but they’re all likely tornado families. The Yazoo City tornado on 4/24/10 was on the ground for 149 miles (maxing out at an incredible 1.75 miles wide as well), which may be the second longest confirmed path.

There are a few other tornadoes with path lengths well over 100 miles, three of them coming in the span of a few hours on 4/27/11, but nothing approaching the 174+ miles of the Tri-State. Just incredible, terrible luck for it to have formed in pretty much an ideal location in relation to the larger system.

The November 21-23, 1992 outbreak, in addition to a tornado in Mississippi with a 128-mile long path, also spawned an F3 in North Carolina that had a path length of 160 miles. Haven’t been able to find much detailed info on it, but various online articles seem to confirm its occurrence.

http://www4.ncsu.edu/~nwsfo/storage/cases/19921122/

Tornadoes with 100+ mile long paths, however, seem to almost always occur in “Dixie Alley”, which is what makes the Tri-State really stand out to me, given the region of the country it occurred in. Do researchers have any idea what allowed it to stay on the ground for that long, was it in some sort of “sweet spot”?

The 160-mile path was likely a family of several (three? five?) tornadoes that just wasn’t thoroughly surveyed because of the many rural areas that it tracked through. Unfortunately once it goes in the official record at a given path length, it’s generally widely accepted and cited as such. The Brandon, Mississippi

As for the Tri-State tornado, I may add an addendum to this post to try and explain some of that. We may never know all the details, but there were several things that contributed to the extraordinary violence and length. The first thing is that the supercell (and hence the tornado) did indeed form in something of a “sweet spot,” being located very close to the center of the surface low and probably near or slightly east of the triple point. The supercell was probably moving around 10mph faster than the surface low, so while it did outrun it eventually, the supercell maintained a similar relative position for a long time. The low was also deepening throughout this period.

The second piece of the puzzle was a very strong baroclinic zone (temperature gradient) associated with the warm front. This was further reinforced by the rainy, dreary weather earlier in the day that kept the cool side of the boundary even cooler than usual, and it also slowed the northward movement of the surging warm front. This allowed the supercell to track right along the boundary — probably just slightly on the cool side, where such tornadoes are most common — for virtually its entire lifespan, providing ample vorticity and a steady influx of warm, moist air for the storm to ingest. We’ve known for some time that existing boundaries are often associated with significant, long-duration tornadoes, but it isn’t often you get a situation quite like this.

A few papers dealing with tornadoes and boundaries, if you’re interested (full papers can be read by clicking the “PDF” option):

Markowski et. al. 1998: http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/1520-0434(1998)013%3C0852%3ATOOTIS%3E2.0.CO%3B2

Rasmussen et. al. 2000: http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/1520-0493(2000)128%3C0174%3ATAOSTW%3E2.0.CO%3B2)

Another well-known example of a tornado “riding” a boundary is the Hackleburg-Phil Campbell tornado from 4/27/11. Although the synoptic situation was different, there was an obvious boundary that likely played a role in the incredible sustained violence of that tornado as well. In fact, I consider Hackleburg to be a pretty good analog for the Tri-State tornado — though, again, not the synoptic setup that produced it. They both left high-end (E)F5 damage across an extraordinary distance, and the Tri-State tornado was probably very similar in appearance to the Hackleburg tornado during most of its lifetime, except possibly during its multivortex periods. Anyway, several other tornadoes on 4/27, including the Cullman, Smithville and Rainsville tornadoes, may have interacted with the boundary as well.

A nice presentation on the boundary that day from one of the AMS conferences:

https://ams.confex.com/ams/26SLS/webprogram/Paper212184.html

There were surely other factors as well, mesoscale stuff that’s impossible to pick up through the fog of time, but synoptically it was just about a perfect setup for producing an extremely long-track tornado. And of course the extremely rapid forward motion was a factor in the path length as well, as is the case with all other long-track tornadoes.

Did the 2010 Yazoo City tornado “ride” a boundary as well? Or did something else cause it to maintain an exceptionally long path?

Yes it did. There’s a good paper by Samantha Chiu on the role of the mesoscale environment in producing and maintaining the Yazoo City tornado. As a general rule, most long-track tornadoes are enhanced by a boundary interaction of some sort. That’s especially true of exceptionally long-track (100+ mile) tornadoes. In the case of Yazoo City, it was also aided by absurdly high shear and helicity. The 0-1km helicity in the near-storm environment peaked as high as 1,000 m²s², which is virtually unprecedented. The instability wasn’t extreme, but at 3,000 to 3,500 j/kg it was certainly more than adequate even with the extraordinary shear.

Shawn,

I think that Charles Holmes is my great grandfather. My grandmother and her 4 siblings were orphaned by the tornado. But you only list 2 of the girls. I don’t know if just two had injuries but i know that my grandmother had a dip in the calf of one leg that she had said a stick went through her leg. She and her siblings, Una Bertha, Erma, Ida, Delbert and Dewey Holmes were under the kitchen table when it struck. They were taken to Indiana and distributed among relatives after their parents deaths.

Thank you for posting, Tina! I could only find information on the two injured daughters, so I assumed they were the only children. I’ll make a note of that and update my post shortly. Are there any family stories about the tornado? It’s obviously a very traumatic experience, and everyone seems to handle it differently. Some people never really talk about it, while others pass on the story to later generations. There are thousands of family stories across Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee and Kentucky from that day.

Great post Shawn. One of the best books I ever read about this disaster was “The Forgotten Storm” by Wallace Akin, who survived the tornado as a 2-year-old in Murphysboro (his family’s house was destroyed, and his father was seriously injured but recovered). He relates some very haunting stories from this tornado. One was of a young girl, think she was about 11 or 12, from Gorham who with her mother and other women went to a makeshift morgue and helped clean dirt and debris from the bodies of their neighbors and friends to prepare them for burial. Another story was of an injured woman who had been impaled by a wooden board that could not be removed; nothing could be done for her, except wait for her to die. How people ever got over experiencing things like that, I don’t know — a lot of them probably didn’t. Akin himself writes that when as a boy he asked one of his uncles about the tornado, the uncle said simply, “I never talk about that.”

Thanks Elaine. I’ll have to pick that book up, it sounds good. People moved on because they had to, but I think many survivors never really came to terms with what they saw and experienced. Local newspapers occasionally did interviews with survivors on various anniversaries of the event, and you could tell that for many there’s still a lot of raw emotion just under the surface. It certainly didn’t help that many of them took the same approach as Wallace Akin’s uncle — “we just don’t talk about it.”

It’s difficult to imagine what the survivors dealt with. I read one account where a small girl was in her home with her mother and brother. The girl and her mother were thrown from the house when the tornado hit and were knocked unconscious. When the girl came around, she saw that her mother had been cut almost entirely through both her left wrist and ankle, to the point that she was gushing arterial blood. Although the little girl was also severely injured, she managed to rip up her dress to try and tourniquet her mother’s wounds until help could arrive. Her mother died on the way to the hospital. The brother was very badly injured and had his skull fractured in several places, but he miraculously survived. I believe this was in Griffin but I’m not positive.

I think even worse than the tornado was the fire, especially in Murphysboro. Many of the people who survived the tornado ended up trapped in basements or under rubble. Because of the massive scale of the disaster many of those people couldn’t be rescued, and many of the children later recounted hearing their screams as the fire swept through and burned them to death. I can’t imagine what it must have been like to be there. My grandfather served in World War II and I think there are a lot of similarities. In both cases they witnessed things that the rest of us can hardly fathom, and although the experience never really left them and they never fully confronted it, they simply moved on because they had no choice. It’s terribly sad, but it’s also an incredible display of strength and perseverance.

I agree. Akin notes that his family and others had a neighborhood storm shelter built after the tornado and that he made numerous trips there as a kid, with his grandmother always bringing a bag full of toys, snacks, etc. for him. He also mentions a couple of his acquaintance who lost their only child in the tornado (believe it was when Logan School collapsed) and sort of “adopted” him afterwards — they’d fix him a snack and let him play with their son’s toys whenever he came to visit, and tracked his progress through high school and college.

There was another violent tornado outbreak in the same area 32 years later, just before Christmas (!) of 1957, in which Murphysboro was hit by an F4 with, I believe, 10 fatalities. An F5 was recorded in Perry County (IL) from this outbreak. That had to be really traumatic for survivors of the Tri-State Tornado, many of whom were still around at that time.

Something else I’m curious about: where did those colorized pictures come from and how was that done? It makes those pictures look like they were taken in the 1950s.

They’re great, aren’t they? They’re from the Jackson County Historical Society. The negatives are in black and white of course, and then they were put on glass slides that were hand-painted the appropriate colors. I’m glad you mentioned it actually, I’ve been playing around with painting some of the old black and white photos in Photoshop but I totally forgot about it. I fear I’m not nearly as artistic as the folks who did the originals though, haha.

Yes, the 12/18/1957 tornado took a very similar path through Gorham, Murphysboro, De Soto, Hurst and dissipated near Plumfield. It may also have started just across the Mississippi River on the Missouri side. It’s not often (or ever, actually) that you see such a violent outbreak, much less in Illinois.

There was also an F4 that occurred on September 22, 2006 starting in Perry County, Missouri and crossing the Mississippi River into Jackson County, Illinois, passing near Gorham and dissipating near Murphysboro. Didn’t do any damage to them, however, and had a much shorter path length. Still, I figured it might be worthy of note:

http://stormhighway.com/sept222006.shtml

I assume the Tri-State likely have a similar appearance, assuming it was clearly visible and not rain-wrapped?

Yeah, I suspect that’s probably similar to the Tri-State tornado’s appearance. Any of the big, nasty wedges, really. I remember Crosstown but I’d forgotten that it passed near Gorham/Murphysboro. What a monster tornado.

It’s true that you don’t often see violent tornado outbreaks in Illinois… but the funny thing is, when they do happen, they occur outside of the “traditional” tornado season (March-June) more frequently than one might suspect. There have been only two officially ranked F5 tornadoes in Illinois since 1950; one (noted above) occurred in December and the other (Plainfield, 1990) occurred in late August (the only August F5 to date in the U.S.).

One last historical footnote: the Orient No. 2 mine at West Frankfort experienced a terrible explosion just before Christmas in 1951 that killed 119 miners. It was dubbed the “Black Christmas” disaster:

http://thesouthern.com/news/black-christmas-a-coal-miner-remembers-when-died/article_0a8a4146-f064-5ee0-9f23-2fb548c0b893.html

Between that and the violent tornado deja vu in ’57, if people living in that area of Southern Illinois in the 1950s came to dread Christmas, I wouldn’t blame them!

Right, I’d forgotten about the mine explosion. I read about it in one of the Illinois history books I came across in my research. Talk about terrible luck.

There was also an alleged “Tri-State Tornado” on June 5th, 1805 that I considered including in this article but there wasn’t enough information available. I suppose that isn’t surprising considering Illinois wasn’t even a state yet. In any event, it apparently began in far eastern Missouri, crossing the Mississippi near present-day Barnhart, MO (a bit south-southeast of St. Louis) in a northeast or east-northeast direction.

There are reliable reports of damage until you get a few miles northwest of Mt. Carmel, where the reports apparently end. There were unconfirmed reports that the tornado may have continued on all the way to Indiana, though. The truth has been lost to time, but it’s a very interesting event nonetheless. It was probably a tornado family with two or more significant tornadoes, but all we really have is speculation. The tornado(es) apparently caused such significant, widespread damage to the forests that it was an obstacle for pioneers heading west for many years.

Amazing article! Just curious if you will be doing a post on the 2013 Moore tornado?

I considered it immediately after it occurred, but I don’t think there’s much I can add that hasn’t already been covered in some form or another. That, and I have such a huge backlog of events (both tornadoes and hurricanes). I think the most significant aspects of the Moore tornado were the apparent effect of storm mergers (which we’ve seen several times with violent tornadoes — probably a topic for a future post) and the terrible incident with the medical examiner’s reported death toll. It’s obviously infinitely better to go from a reported 91 deaths to 23 than vice versa, but it’s unbelievable that such a huge number could be released, even unofficially, without a high degree of certainty.

Man, this article was truly epic. I felt like I was hearing this story told around the campfire by an exceptional storyteller. There were many times that I could switch to (in my mind’s eye) a POV from either the tornado or its victims. ..

The thing that I most admired of this article were the sections on the outbreak in Kentucky and Tennessee (and possibly more of the Southeast)…this is probably the first really detailed article about it outside of scientific/scholarly references. I only wish more info was available on it.

Really, I’m surprised Hollywood hasn’t made a movie about this event, it would likely break summer box office records. I’m currently working on an epic poem about the Tri-State, basically narrating it’s path of destruction. This article has given me some excellent ideas.

Thank you, John! I posted a reply earlier from my phone but apparently it disappeared. In any case, there’s an almost endless source of both heartbreaking and inspiring stories contained within the larger Tri-State tornado event. I wish I had more time to dedicate to that aspect. As for the rest of the outbreak, it’s a shame that there isn’t more information available. I was able to find quite a bit via digging around in newspapers, historical societies and various other sources, but there’s always so much more I’d have liked to track down. It’s unfortunate that so much information about these historical events has been lost to the passage of time, so it’s nice to be able to preserve some part of it.

As for making a movie, I think it lends itself quite well to the big screen. I suppose they’d be afraid that it would only appeal to weather nerds, and who knows, maybe they’d be right. I think it’s a tremendously compelling event from which you can draw hundreds or even thousands of stories. I feel the same way about the 1900 Galveston hurricane (along with the obvious theme of arrogance toward nature that permeated almost every aspect of that disaster).

“I’m surprised Hollywood hasn’t made a movie about this event”

Bill Paxton of “Twister” fame has proposed doing a “Twister” sequel that might incorporate, or be based on, the Tri-State Tornado, and actually took the time to visit the area and trace the Tri-State’s path. However, it’s been 3 1/2 years since this interview was published and it appears no one has taken him up on this idea:

http://www.premiumhollywood.com/2010/01/07/bill-paxton-is-up-for-a-twister-sequel-anyone-else/

Bill Paxton in 1925? I’d watch it, haha. I’ve heard for a while that he’s been pushing a Twister sequel, including getting partial funding from something like Kickstarter. Twister was cringe-inducingly inaccurate, but I still watch it whenever it happens to be on.

Whenever you get the chance, check your email. I sent you some new stuff I found out about this event (and the 1904 one as well). Yes, that includes pictures.

Hmm, did you get the wrong email address? I don’t see anything from you. Sounds interesting though, I look forward to it! I also have probably a couple dozen photos from the Tri-State tornado that I didn’t use, I was going to post them somewhere but I forgot about it. I should probably do that.

I clicked on the email link on your about page and it gave me gmail address. Hopefully it went through this time.

Bill Paxton hasn’t given up on his Tri-State Twister sequel idea, as evidenced by this interview from about 2 weeks ago:

http://www.craveonline.com/film/articles/538553-comic-con-2013-bill-paxton-talks-7-holes-kung-fu-and-a-twister-sequel

“I went on a trip with a guy named Scott Thompson. He played preacher in Twister. He’s an old friend of mine. We did a road trip where we tracked the trail of the Tri-State and we went to all the old historical societies. The one which we went to was Murphysboro. The headline, it’s an aerial shot, it just looks like WWII bombed out city. It said, “In the blink of an eye, Murphysboro is gone” and we saw it because some of the old timers there, you know what they say? They say if it happened once…

“Now, can you imagine, we’ve seen some very deadly tornadoes in the last few years. These ones that hit Oklahoma this year, the one that hit Joplin a couple years ago. They’re just death and destruction because these are now very populated areas. The midwest is populated now. Can you imagine something on the magnitude of a Tri-State coming through there? That would be the third act of the sequel….It’s going to hit St. Louis and it’s going to take the famous Arch and just twist it like one of those ribbons.”

Wow, it appears I have found a kindred spirit. I have been studying and researching weather and weather history for almost nine years now. I’m due to graduate with a BS in meteorology from the University of South Alabama in December. I’m amazed and humbled by the richness and detail of the posts on your site. For the past three years, I’ve been working on my F5/EF5 “Chronology”: http://ericsweatherlibrary.com/the-chronology/

with write-ups on all documented F5/EF5 tornadoes dating back to 1880, using the research of Tom Grazulis for the pre-1950 storms. I recently finished the final updates and am about to begin adding pictures. I have a Google Earth file, but wordpress won’t let me post it. Now since finding your site, I feel thoroughly upstaged lol. Just amazing the stuff you’ve compiled. Please get in touch with me. I’d love to talk weather with you. – Eric Brown

Thank you Eric! I just poked around your site a bit, looks like great stuff! I’ve bookmarked it so I can take a closer look through it tomorrow, that must have been a ton of work. I see you’ve done something similar with tropical systems, too. I’ve been meaning to tackle a couple hurricanes but I keep drifting off into other projects. Anyway, I’m excited to read through your site. I’ll send you an email tomorrow.

Thanks, I look forward to it. I’d love to hear where you got some that incredible detail, particularly on those old events. I’m not happy with my pre-1900 stuff. New Richmond, the 1898 event and Rochester aren’t too bad but Pomeroy, Grinnell and others are a little thin. But overall, I’m very pleased with how it turned out. I think once I add some pictures, it’s gonna look awesome. Yeah it was a lot of work. I spent the better part of three years working on it, but it was a labor of love and when you love what you do, it really shows. I’ll bookmark your page as well. I look forward to seeing some of your future work. – Eric

Ripping railroad tracks out of the ground? That could actually be a good way to get an estimate on wind speed, even all these years later. Of course, you’d have to base it on the smaller rails of the day, but that shouldn’t be difficult, there’s still track like that in use in places. I’m curious, are there any pictures of that track? Was it still attached at each end by the rails, and just thrown off the roadbed, or were the rails severed? (Likely at the joints – they were bolted back then, and often still are today.)

And more then likely, it was a case of the gravel ballast being scoured so much that the track came with it.

Know of any other cases of tornados ripping up railroad tracks?

PS – Wondering if the tri-state tornado destroyed more buildings then the Joplin tornado. Know how many blocks the Joplin tornado destroyed? The tri-state destroyed 152, plus 15 more burned down in Murphysboro, according to (I think) Akin’s book, which actually disagrees with your article. Not that I’m saying you’re the one whose wrong.

Actually, I think the Joplin tornado might have destroyed more, but it had more buildings in its path. But then again, the Joplin tornado had a path hardly longer then Joplin, but if the tri-state tornado had 2, or 4, Joplin’s in a row, it would have cut a swath through all of them.

Then again, I somehow only noticed just know that ‘only’ 600 were injured in Murphysboro, which is actually less then Joplin – then again, Joplin is much bigger.

PSS – Great article, just had to write a paper for class (8 pages), and you were more useful then Akin’s book and another one I can’t remember the name of.

Thanks Everett, glad you found it helpful. By the descriptions it sounds like sections may have been torn away at the joints, since at least one account mentions pieces of the tracks being “thrown,” but I can’t say for sure. I would assume you’re correct about the track ballast being swept away, since ground scouring was noted in at least one area where railroad tracks were ripped up. I wasn’t able to find any photos unfortunately. I seem to recall coming across similar descriptions while researching a couple of different tornadoes, but the only one that comes to mind right away is the May 15, 1896 Sherman, Texas tornado. There were accounts of railroad tracks just outside the town being ripped up and “twisted and mangled.”

Re: the number of buildings destroyed, the count for the Tri-State tornado is very uncertain. Estimates range from as low as 4,000 to as high as 15,000. I think the real figure is probably somewhere in the middle, and my best guess would be between 7,500 and 10,000. The official count for Joplin also varies a bit from source to source, but the most common figure seems to be right around 7,000. The Tri-State tornado probably destroyed more structures, but the fact that the Joplin tornado did the vast majority of its damage in the span of about six miles is extremely impressive.

Regarding injuries, I don’t think the counts are very accurate. In the past, and especially as far back as the 1920s, only people who suffered significant injuries tended to seek medical attention right away. Many people treated minor injuries at home, and the injury count often doesn’t include those who sought medical attention days or weeks later. That isn’t the case today, where most (though still not all) of the people who are injured will seek medical attention and be included in the injury total, even if it’s several days later.

Thanks. Considering that none of the sources I could find even gave an estimate, your research skills are a lot better then mine. Also Akin’s book, I believe, listed only 1,200 builings destroyed in Murphysboro, which considering the estimates above, is almost certainly very wrong. No wonder a lot of people consider the book to have problems. Any idea where some of those estimates came from?

Oh, were you talking only the damage in Murphysboro? My figures were for the whole tornado. For Murphysboro alone the figure would obviously be a lot lower; 1,200 seems low but it probably isn’t too far off in that case. I’ve not read Akin’s book so I don’t know much about his research. Weather books written for the general public tend to be rife with inaccuracies, but I know Akin was a professor of some sort so I assume he did a better job with that.

Ok, now I’m confused. Parrish, Gorham, Griffin, and Annapolis, I don’t believe, had more then 500 buildings between them before the tornado. I figured that Murphysboro would have the most buildings destroyed, and along with Princeton and West Frankfort (several hundred buildings destroyed), and to a lesser extent DeSoto, would make up the bulk of the destruction.

Is it that most of the buildings destroyed were in rural areas, rather then towns? If 7000 structures were destroyed, that would have to be the case.

BTW – know where I can find those estimates? Google doesn’t seem to produce any results. I wonder if the reanalysis project could provide a firmer estimate.

Ditto on most of the injured not being recorded – there wasn’t enough medical care for them to receive anyway.

Sorry for being unclear. As I said, I do think the 1,200 estimate for Murphysboro is low, but it doesn’t seem as though the city was particularly densely built. If I had to speculate I’d say ~2,000 structures, give or take several hundred. Regarding Annapolis, Griffin, Gorham, etc., while they weren’t large towns by any means, I’d say there were well over 500 structures destroyed between them. Much of the damage did take place in the various cities and towns, but there were also a considerable number of homes and other structures in the more rural areas that were destroyed.

I haven’t had time to dig too deeply to come up with better answers for you, but after a quick check I found a few useful figures. According to George W. Smith’s “A History of Illinois and Her People,” about 120 blocks were destroyed in Murphysboro. Other figures they provide are “but two houses left out of more than 100” in Parrish, 154 residences in DeSoto, 300-400 completely destroyed and “scores more” damaged in West Frankfort, and 19 destroyed in Hurst-Bush. Some of these numbers seem to be low as well, and I’m not sure what their sources were.

The highest total estimate that I’m aware of (15,000) comes from the Paducah NWS office. I emailed them to enquire about their sources when I was researching this article, but I never got a response. Maybe I’ll try it again. It doesn’t look like a great deal of research went into their page, so I don’t put much stock in it.

http://www.crh.noaa.gov/pah/?n=1925_tor_ss