[NOTE: Mouse over or click on individual photos for larger versions and more info. Also, I’ve created an interactive map of the outbreak to make it easier to follow along. It includes every known tornado track as well as every fatality, so feel free to zoom and pan around or navigate via the menu on the left side of the screen.]

While this article was meant to be read as one piece, I realize it can be a bit overwhelming. To that end, I’ve included a table of contents that should hopefully make navigation a little easier:

- Niles Park Plaza

- The Elevated Mixed Layer

- The Prelude

- Trouble Brewing

- Rush Cove, ON F2

- A Wicked Breeze

- Where the Hell Is This Thing?

- Hopeville, ON F2

- Corbetton, ON F3

- Grand Valley, ON F4

- Lisle, ON F2

- Barrie, ON F4

- Tornado Watch #211

- Albion, PA F4

- Mesopotamia, OH F3

- Linesville, PA F2

- Atlantic, PA F4

- Corry, PA F4

- Saegertown, PA F3

- Centerville, PA F3

- Wagner Lake, ON F2

- Reaboro, ON F2

- Alma, ON F3

- Ida, ON F2

- Rice Lake, ON F3

- The Spark Arrives

- Niles, OH-Wheatland, PA F5

- Tionesta, PA F4

- Johnstown, OH F3

- Tidioute, PA F3

- Undocumented Tornadoes

- New Waterford, OH F3

- Moshannon State Forest F4

- Dotter, PA F2

- Kane, PA F4

- Beaver Falls, PA F3

- Elimsport, PA F4

- Drums, PA F1

Niles Park Plaza

The sky grows dark and threatening as swollen storm clouds roll in from the west, extinguishing the late-afternoon sun. Shade trees bend and creak in protest, their broad canopies quivering in the wind. Rain comes in fits and starts, spattering against the windshield in fat, heavy droplets.

None of it matters to Ronnie Grant. After one of the proudest and happiest days of his life, a few thundershowers won’t dampen his spirits. His daughter has just graduated high school — in a few months, she’ll begin her scholarship at a prestigious university halfway across the country. In the meantime, he and his wife Jill are heading out to celebrate at their favorite local restaurant.

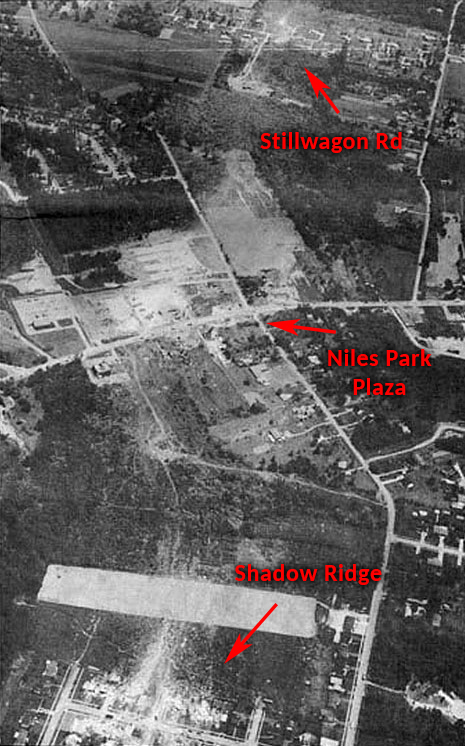

A lineman for the utility company, Ronnie has lived in Northeast Ohio all his life. He’s driven this stretch of U.S. 422 so many times he can do it in his sleep, arcing north and west from Girard through the outskirts of Niles. As he crests a hill overlooking a commercial strip on the city’s northeast side, the gossamer veil of rain begins to lift.

His wife gasps and stiffens in her seat. He opens his mouth to speak but the words catch in his throat. Something is terribly wrong, and suddenly the whole world is unmoored from the flow of time. Seconds linger like minutes, unfolding in a stilted, stop-motion fashion that only adds to the deep and pervasive sense of unreality. Without thinking, he instinctively pulls off the highway and slides to a stop.

He can hardly process what he’s seeing, yet every image is seared into Ronnie’s brain with inexplicable and excruciating clarity. The black, debris-choked funnel, looming like a vast shadow against the sky. The familiar outlines of homes and businesses forever disappearing, consumed in an instant by a violent, seething darkness.

The monster moves with manic energy, rapidly crossing U.S. 422 and sweeping into Niles Park Plaza. Fragments of lumber and aluminum and steel erupt in all directions like the blast wave of a grenade. Roofs and walls sail away and break apart, adding to the ever-growing cloud of wreckage.

A large, bright-colored object whirls up into the air, spinning like a helicopter. And then another. And another. The shapes are distinct and immediately recognizable — vehicles. Ronnie’s stomach turns at the realization, but he can’t look away. He watches helplessly as one car is torn apart, disgorging its occupants. Within moments, they disappear into the middle of the raging maelstrom.

They will not be the last.

The Elevated Mixed Layer

It began with a deliberate slowness, as things often do in the American Southwest. The late-spring sun burned above the Llano Estacado, a muted sea of dirt and grass and scrub that slopes gradually into the stark canyonlands of the Pecos River Valley. Intense solar radiation cut through the lacquered blue of a perpetually cloudless sky, baking the desiccated landscape.

Through the final days of May 1985, the scorching sunshine cooked up triple-digit temperatures from northern Mexico to central Oklahoma. Roiling with thermal energy, the superheated air near the surface rose in great convective currents while cooler, denser air sank toward the ground. This slow and steady churning created a deep, stable, uniform airmass over the high mesa.

Further north, a progressive trough moved swiftly toward the Northern Plains, bringing with it a powerful 70-knot jet streak. At the surface, a low-pressure system developed in the lee of the Rockies and intensified as it moved into the Upper Midwest. In response, the well-mixed airmass over the Desert Southwest began to push eastward.

On the 7 am surface map from May 30, a broad area of low pressure was beginning to develop in the Northern Plains.

Reaching the lower elevations around the Mississippi Valley, this stable airmass overspread a vast pool of warm, humid air flooding in from the Gulf of Mexico. Acting like a lid on a pot, the resulting elevated mixed layer (EML) effectively suppressed convection beneath it, allowing tremendous energy and instability to build without boiling over.

Analysis showing the edge of the lid (double solid line) at 8am May 30. (Adapted from Farrell 1989)

The Prelude

By Thursday afternoon, May 30, the deepening surface low had moved into western Minnesota. A warm front extended across the Great Lakes, while a strong cold front trailed south into Kansas and Oklahoma. Meanwhile, the elevated mixed layer had continued spreading to the east and north, expanding in a broad arc from northern Iowa to central Kentucky.

As unstable, moisture-rich air pooled beneath this atmospheric lid, trouble began brewing along its edges. A line of storms formed near the cold front, producing baseball-sized hail in Missouri. Brief spin-ups throughout the evening caused moderate damage in parts of North Dakota, Wyoming, Montana and Minnesota.

At about 10:30 pm, a large supercell fired along the northern edge of the EML in northeastern Iowa. Feeding on the untapped supply of warm, moist air, it quickly strengthened and produced a tornado in rural Clayton County. The destructive twister struck entirely without warning, badly damaging about two dozen farms and causing several injuries.

As it passed north of Elkader, the tornado leveled the south wing of the Clayton County Care Facility. The collapse of the concrete structure killed two elderly residents and hurt several others. Crossing the Mississippi River into Wisconsin, the tornado leveled a large farmhouse near Bagley, seriously injuring a woman and her son. It continued for another 10 miles, tearing through nearly two dozen farms and producing significant damage across central Grant County.

The storm promptly reorganized as it moved across southern Wisconsin, producing subsequent tornadoes in Iowa and Dane counties. During the overnight hours, additional storms broke out over parts of Ohio, bringing small hail, gusty winds and torrential downpours to the eastern half of the state. Though no one could have known it at the time, the drenching rainfall only served to add fuel to the coming fire.

Trouble Brewing

Spirits were high as the sun spilled over the northern reaches of the Ohio Valley on Friday morning, May 31, 1985. A tangible sense of excitement permeated the air as children prepared for their last day of school, the endless possibilities of summer stretching out before them. Others anxiously awaited their graduation ceremonies — or simply the end of another work week.

Few people took notice of the morning severe weather outlook issued by the National Severe Storms Forecast Center (NSSFC) in Kansas City. The center had been monitoring the atmospheric conditions for several days, watching with growing concern as pieces began to fall into place. Even with the relatively primitive technologies of the time, NSSFC forecasters could recognize a troubling pattern when they saw it.

With an unseasonably deep low-pressure system pushing into a highly unstable airmass, backed by a dynamic and well-timed upper-level trough, the NSSFC included a Moderate Risk on its 4 am outlook for much of the Northeast and Great Lakes. Going a step further, the outlook explicitly mentioned that a “significant severe weather episode” was expected.

Not much had changed by 11 am, when the NSSFC was scheduled to produce its second daily weather outlook. In fact, the meteorologists had become even more confident in their forecast, issuing a much smaller Moderate Risk area that pinpointed eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania and western New York as the areas of greatest concern. With the picture seemingly coming into clearer focus, all that remained was to refine the details for the day’s final 3 pm outlook.

By 7 am on May 31, the surface low had begun moving into the Great Lakes region.

A loop of 500mb heights shows the developing shortwave swinging into the Great Lakes.

Rush Cove, ON F2

As the sprawling low-pressure system moved over the Great Lakes through the early afternoon, it pulled in a conveyor belt of steamy tropical air. Beneath the EML, which covered most of the Ohio Valley, brilliant blue skies provided ample sunshine. The atmosphere bubbled with convective energy.

Analysis showing the edge of the lid (double solid line) at 8am May 31. (Adapted from Farrell 1989)

Beyond the northern edge of the lid, a stiff southerly flow transported rich moisture across the Canadian border. Weather stations as far north as Central Ontario reported dewpoints in the middle and upper 60s. When the potent cold front began pushing into the region from the west, isolated thunderheads quickly developed over Lake Huron and the Bruce Peninsula.

Around 2:45 pm, the line of storms produced the first tornado of the day near Hopeness, a small farming community 15 miles north of Wiarton. Hurrying off to the northeast, the fledgling tornado quickly solidified. It began uprooting trees and breaking off large limbs, lofting them into the air and carrying them along.

On a small farm on Rush Cove Road, Roger Meneray and his family were visiting with a friend in their living room when he noticed strange movements outside. He peered out the window just in time to see a “vicious-looking” white funnel come into view through the trees. Tall and slim and barely 80 yards wide at its base, the needle-like whirl glinted and shimmered in the front-lighting of the midday sun.

Unable to tear his eyes away, Meneray looked on as the compact cone cut a diagonal swath across his property. His barn and tool shed collapsed into a heap of broken boards and beams. The van in his driveway slid and spun across the ground, ending up 25 feet away facing the opposite direction. His small sailboat sailed some 80 yards across the sky; his aluminum rowboat disappeared entirely.

The wreckage of Roger Meneray’s barn.

In a flash, several windows blew out and the siding was stripped off the south side of the house. Luckily, no one was hurt and there was no major structural damage to his home. Although the barn was mostly leveled, a pony tied up in its stall was unharmed and even continued to munch on hay, seemingly unfazed by the experience.

Several other farms around Hopeness experienced similarly close calls, losing flattened barns and outbuildings but sustaining minimal damage to homes. There were no known injuries in the area, although one horse suffered minor lacerations from flying wood. One truck was reportedly flipped onto its roof.

After tearing through the Meneray property, the tornado began to strengthen and grew to approximately 175 yards. It “clear-cut a section of bush” along the escarpment overlooking the coast, snapping off trees and depositing twisted bits of debris over a few hundred yards. Before it could intensify further, however, it moved out into Rush Cove and quickly roped out over the waters of Georgian Bay.

At the time, few could have guessed the minor spin-up would mark the beginning of one of the most violent — and unusual — tornado outbreaks in history. And yet, even as the storm weakened and dissipated, the first seeds of disaster were being sown less than 100 miles to the south.

A Wicked Breeze

With most of the region still enjoying unbroken sunshine, the atmosphere across the Ontario Peninsula was becoming more unstable by the minute. As the hot, humid air began to rise freely, the air over the surrounding Great Lakes — cooled by the moderating effects of the water — flooded ashore to take its place.

The leading edges of these airmasses formed lake-breeze fronts that spread northward from Lake Erie and southeastward from Lake Huron. Along these boundaries, cooler onshore flow plowed into the warm, buoyant airmass already in place, wedging beneath it and forcing it skyward. The lake-breeze fronts progressed inland through the early afternoon, pushing into the center of the peninsula just as the cold front arrived from the west.

The collision of contrasting airmasses generated tremendous lift, increasing vertical motion in the atmosphere and fueling vigorous convection. Intense updrafts exploded into towering supercells. Feeding on enhanced convergence and vorticity along the boundaries, they quickly overspread nearly the entire northern half of the peninsula.

What began as a refreshing lake breeze on a hot, muggy day had turned into the match that lit an atmospheric inferno.

Where the Hell Is This Thing?

Nearly 800 miles southwest of Ontario, officials at the National Severe Storms Forecast Center in Kansas City were vexed. So, too, were meteorologists in Cleveland, Buffalo, Pittsburgh and other weather offices across the Northeast. Their calls seemed to be coming into the forecast center with increasing regularity, but the refrain was always the same: “Where the hell is this thing?!”

When NSSFC forecasters issued a Moderate Risk in their 11 am severe weather outlook, they were confident they’d see the beginnings of a significant outbreak developing in the Northeast by mid-afternoon. As the 3:30 pm deadline for the day’s final outlook rolled around, however, the latest satellite imagery showed nothing of the sort. In fact, there was hardly a cloud in the sky.

Poring over the latest maps and data reports, Steve Weiss found himself just as conflicted as everyone else. His instincts, sharply honed through years of experience as an NSSFC lead forecaster, told him the classic pattern for a significant severe weather episode was still on track for the northern Ohio Valley.

There was the unseasonably strong low-pressure system and its associated frontal boundaries. The well-defined shortwave moving through the Upper Midwest, supported by a potent jet streak at its base. The tinder-box instability that continued to build. And yet, all of the available data seemed to suggest the violent storms brewing over Southern Ontario were likely to be the main — perhaps only — show.

With the afternoon outlook due and radar scopes across the area still unexpectedly clear, Weiss and his team faced an agonizing dilemma. Continuing with a Moderate Risk would imply a much higher level of confidence than they felt, risking unnecessary alarm and eroding public trust. If storms did fire, however, there would be little to stop them from reaching their explosive potential.

With no small degree of trepidation, the NSSFC crew opted for a conservative approach. Although they continued to emphasize the possibility of intense storms and tornadoes, they resignedly downgraded the outlook for Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York to a Slight Risk just after 3:30 pm.

Hopeville, ON F2

While meteorologists puzzled at the lack of activity across Ohio and Pennsylvania, things were rapidly going downhill north of the border. As a line of powerful supercells spread over the heart of Southern Ontario, the northernmost storm lashed the pastures and hayfields of southern Grey County. A barrage of heavy rain and hailstones as large as tennis balls pummeled roofs and vehicles from Holstein to Mount Forest.

Around a quarter to four, the swirling winds beneath the supercell’s updraft began to coalesce. Tightening into a slender but potent vortex, the budding tornado made contact just outside the hamlet of Maple Lane. Moving swiftly off to the east-northeast, it demolished several barns, sheds and utility buildings as it tracked about a mile south of Hopeville.

Although it remained on the ground for just over 10 miles, ending south and east of Ventry, the twister’s path through the wide-open countryside presented few opportunities for destruction. Aside from some leveled outbuildings, it left only patches of intense tree damage to mark its passing. No known injuries were recorded.

Corbetton, ON F3

Just off Ontario Highway 10 in Corbetton, a dozen miles east of Hopeville, 45-year-old carpenter Walter Lloyd was nursing his drink at the Skylight Restaurant. He watched as crisp, cottony clouds sprouted up over the horizon and piled up like a traffic jam. By the four o’clock hour, the sky had turned dark and swollen with rain. Less than enthusiastic about the thought of driving in a downpour, he settled up and headed for home.

As he drove out of town, he couldn’t help stealing peeks at the mountainous mass of clouds. It seemed almost alive, “black as tar and swirling like an eddy.” Within moments, Lloyd caught sight of something that stopped him in his tracks: a long, willowy protuberance dangled from the trailing edge of the storm, its tip “thrashing around like a fire hose under pressure.”

The twister disappeared behind a cloak of rain and battering hail, but there was no mistaking where it was headed. Cutting through the outskirts of Corbetton, it tossed aside large trees and ripped the roof off the Skylight Restaurant, dumping it in a field nearly 200 yards away. Despite the damage, owner Stevo Zderic and his six remaining patrons were unharmed. Several neighboring houses sustained significant damage and one was “sliced in half” when a recently completed addition was smashed to bits.

Weaving through the agricultural area northeast of Corbetton, the tornado steadily picked up speed and strength. Near the intersection of the 5th Line and 20th Side Road, Earl Looby stood at his cellar door and hesitated, waiting to get a better look at the storm. Instead, the rain-wrapped funnel blew through with surprising swiftness. It grazed his home and tore away the attached garage, wrecking two snowmobiles and crushing a new motor boat.

Not far away, Jacques St-Denis was home alone with his young sister when the storm’s terrible roar drew close. Leaping into action, he quickly ushered her toward the basement. The siblings reaching the bottom of the steps just as the house above began to come apart.

Less than a mile to the east, several people watched what happened next from a repair shop on Highway 24. A murky curtain of rain and wind engulfed the St-Denis home, spraying a cloud of debris across the countryside. When the dust settled, the house was gone. A well-constructed barn on the property was also demolished.

On their family potato farm west of Highway 24, Harold Wilson and his son Bruce were in the midst of another busy planting season. Gusty rain squalls had briefly forced them to bring their equipment inside, so father and son busied themselves working on a tractor with another farmhand. As the rain let up, Harold was surprised to hear a noise like some giant tractor-trailer or piece of farm machinery rumbling across the property. Perplexed, he headed toward the front of the workshop for a better look.

Suddenly, the large 24-by-14 door exploded in a shower of fiberglass splinters. The three men dove for cover as the workshop “disintegrated in seconds,” raining down debris and blowing equipment through the air. They narrowly escaped death when the heavy shop wall behind them blew outward rather than collapsing on top of them.

As the tornado sliced diagonally across the farm, it blew away several barns and storage buildings, sheared off a 70-foot concrete silo and toppled a full 100-ton fertilizer blender. Of the 18 vehicles on the farm, 17 were destroyed. Pickups, 10-ton trucks and pieces of farm equipment were hurled hundreds of yards and crushed. Two tractor-trailers were thrown or bounced a quarter-mile down the road and torn apart. Pieces of vehicles were found on a neighboring farm nearly two miles away.

Still, the Wilsons were somewhat fortunate. The narrow swath of intense destruction missed their farmhouse and several other buildings, resulting in more moderate damage. Although Harold and Bruce were both hurt, no one on the property was permanently injured or killed.

After dealing a blow to the Wilson farm, the tornado continued on a curving path to the northeast. It destroyed the Agrico Fertilizer Plant and wrecked about a dozen more homes and farms as it passed south of Redickville and north of Terra Nova. The 14-mile path came to an end when the twister dissipated just northeast of Ruskview.

Grand Valley, ON F4

While Corbetton residents were digging out from the rubble of their devastated properties, an even more dangerous and destructive storm was roaring to life 30 miles to the southwest. Fueled by an unfettered flow of warm, humid air and enhanced by colliding lake-breeze boundaries, the supercell developed in nearly ideal conditions. At 4:15 pm, the longest recorded tornado track in Canadian history began.

The slithering funnel touched down in an open field near the community of Arthur, snapping tree limbs and blowing down fences as it traveled to the northeast. Passing north of the village, the intensifying twister swiftly tore through a string of farms. Several houses were wrecked and dozens of barns, sheds and other outbuildings were damaged or destroyed.

In addition to the structural damage, the storm also wreaked havoc on local crops. Fields of corn and grain — “the best in years,” according to some — were cut down or littered with wreckage. Utility poles were snapped, cutting off electricity and telephone service throughout the area. On one farm, a multi-ton tractor was rolled around and flipped upside-down.

Like a speeding car, the tornado barreled along Concession Road 2 at tremendous speeds approaching 60 mph. Due to its powerful but compact wind field, farms on the south side of the road were smashed while those on the north were largely unharmed. One woman reportedly napped peacefully on her couch, unaware that anything had happened until she was awoken by a neighbor whose home across the road had been hit.

As Barry Wood finished his beer at the Grand Valley Tavern, his thoughts turned to his horses. A truck driver by trade, the 50-year-old Wood also raced and bred horses at his farm just west of town. When the weather outside began to go downhill, he fished his keys from his pocket and started for the door. Donny Tower, a friend and fellow horse breeder, tried convincing him to stay for one more drink, but his mind was made up.

Wood hopped in his pickup truck and headed west, but he never made it to his farm. A few hundred feet from his driveway, the onrushing vortex emerged from behind a curtain of rain, striking him head-on like a freight train. It lofted his truck into the air, flipping it several times before throwing it into a ditch. Barry Wood was killed instantly on impact.

Barry Wood’s mangled pickup truck. (Courtesy of Dufferin County Museum and Archives)

Continuing northeastward along Amaranth Street, the powerful drillbit tornado swept through the heart of Grand Valley at breakneck speed. About a half-dozen homes were leveled in the town of 1,300 and more than 20 others suffered varying degrees of damage. The rows of majestic maple trees that shaded the quiet streets were broken off or yanked up by the roots and thrown through the air.

The Grand Valley Church of Christ collapsed almost in its entirety. So, too, did the small community medical center and the town hall. A public health nurse was pinned between two doors at the medical center and later had a “large wedge of glass” removed from her neck. Elsewhere, some residents remained buried under flattened structures for hours before being freed.

At the corner of Amaranth and Main, village clerk Les Canivet was working in the municipal office beneath the Grand Valley Public Library. When menacing clouds outside the window threw the sunny afternoon into near-darkness, he sprinted toward the staircase to alert the chief librarian, Shann Leighton. He’d barely reached the bottom step before his voice was drowned out by the deep, discordant howl of the storm.

Canivet scurried back to his office to find shelter as bricks rained down around him. In the library above, Shann Leighton instinctively threw herself to the floor and covered her head. Before she could call out to the others in the library, heavy objects began to collapse on top of her. She lost consciousness.

The sturdy red-brick building, constructed in 1913 with a grant from the Andrew Carnegie Corporation, broke apart in seconds. Brick walls and wooden beams tumbled to the ground. The library’s collection of roughly 7,000 books flew through the air in every direction. In the below-grade municipal office, a large piece of sheet metal sliced through a boarded-up window and went hurtling across the room — precisely where Les Canivet had been sitting at his desk minutes earlier.

After the chaos subsided, Canivet carefully made his way out of the office and up to the library. Only the southwest corner of the exterior wall was left above ground, standing stubbornly above the rubble like a makeshift obelisk. He quickly joined the small crowd that had already gathered, digging with their bare hands to reach those buried beneath the wreckage.

Shann Leighton regained consciousness only to find herself trapped and unable to move. Somewhere above her, the librarian could hear a mother calling frantically for her children. She knew where they had been when the storm struck and could only pray no harm had come to them.

By the time she was extricated nearly an hour later, Leighton’s entire body was covered in scratches and bruises. Soon after, rescuers also pulled the two children from the rubble. Katherine Moore, 7, had been buried under heaps of bricks and books but wasn’t badly hurt. Her six-year-old brother Ricky, who was freed just moments before the rubble pile above him “collapsed in a cloud of dust,” suffered a broken left leg.

Young Kathryn & Ricky Moore sit in the rubble of the library.

Doug Hunter knew something was wrong as he raced home from work, but nothing could have prepared him for what he found when he arrived. The beautiful house he’d recently built on the outskirts of town, perched on a small hill near the banks of the Grand River, was no more. Only the lowest floor, a small walk-out basement, remained standing.

Less than an hour earlier, Hunter’s wife had been hosting relatives in the living room when the storm struck without warning. The mighty winds quickly penetrated an opening at the front of the basement, generating a huge amount of force that sheared the structure from its base and tossed it into the yard. Seventy-year-old Matilda “Tillie” McIntyre, visiting from Scotland, was killed. Her sister and brother-in-law suffered serious injuries.

Meanwhile, 10 miles east of Grand Valley, Stewart Horner was just finishing his Friday shift at Temprite Industries. He hardly noticed the darkening skies as he fired up his 1980 Chevy Monte Carlo, turning north on Highway 10 for a half-hour drive home to Shelburne. Before he’d even made it out of town, however, conditions started going downhill.

A thick blanket of gunmetal clouds swallowed up the sun as he drove, turning the afternoon as dark as midnight. Hailstones began pinging off the roof of the car and shattering on the road ahead. Stewart flipped on his headlights, searching for a place to get off the highway and hunker down. About two miles north of town, he pulled into the parking lot of the Mono Plaza and tucked in beside a large van.

Inside the shopping plaza, Cashway Building Supplies manager Jim Kant was processing an order when he, too, noticed the enveloping blackness. He hadn’t heard anything about severe weather in the area, but his interest was piqued by a faint droning sound that he couldn’t quite place. Stopping to listen more closely, he was alarmed to hear the noise growing louder and more threatening.

A few hundred yards west of the Mono Plaza, Fred and Devon Raymond were becoming worried as well. Though both were blind, they didn’t need sight to recognize that trouble was brewing. The gentle rustling of gusty winds outside had grown steadily louder and more frequent until they melded into a tremulous, metallic wail. The ground beneath their feet quivered and reverberated. Fred quickly pulled his wife to the floor and shielded her, preparing for whatever was to come.

Fred Raymond had spent 20 years building his dream house with the help of his father and a few friends. He’d labored for thousands of hours erecting walls, hanging doors and installing windows built by hand while living in a small Toronto apartment. On weekends, he’d carefully dismantle each new window, carry it with him on a Greyhound bus to Orangeville and reassemble it for installation.

In seconds, the tornado erased nearly half a lifetime of work. The noise was nearly deafening as the wind shoved the Raymonds’ home from its foundation, sending most of the walls tumbling down upon them. A large chimney, heavy enough to crush the couple to death, fortunately collapsed in the opposite direction.

Nonetheless, Fred and Devon Raymond could feel the weight of shattered walls and splintered furniture pinning them to the floor. Once the storm had relented, Devon gave voice to a terrifying thought that had entered both their minds: “Do you think anyone will find us? Do you think they even know we’re here?” They didn’t have to wait long for an answer. Within 10 minutes, their neighbor had arrived and carefully freed them from the wreckage of the house he’d helped build.

Fred Raymond stands in front of the foundation of his house.

Back in the Mono Plaza parking lot, Stewart Horner watched the tornado approach with incredible speed, not fully recognizing what he was seeing until the van to his left began to tumble toward him. Unable to free himself from his seatbelt, he ducked down and braced for impact. The van landed with a crunch, nearly flattening the roof of his Monte Carlo before bouncing along and crashing into several other vehicles. His own car quickly followed, tumbling helplessly like a toy in the furious gale.

When Horner finally came to a stop, he found himself dangling upside-down, still strapped into his seatbelt. With the driver’s side of the car completely crushed, he wriggled out of the tiny gap that had been the passenger’s window. Though dazed and covered in cuts and bruises, he escaped his wild ride relatively unscathed.

Inside Cashway Building Supplies, the low rumble rose to a terrible roar in an instant. Manager Jim Kant quickly urged his customers to get down and seek cover. On the other end of the store, 54-year-old Walter Frena never got the warning, nor had he heard the distant grumbling of the twister’s approach. In fact, like many others in the plaza, he had little inkling that anything was amiss at all — until the store exploded.

Drawn by the sudden commotion, Frena turned around just in time to see a car smash through a nearby plate glass window as if fired from a giant cannon. He instinctively whirled around to look for his wife; instead, he saw an entire section of concrete wall — complete with light fixtures, bathroom cabinets and other display products — crumbling in on him.

Partially buried under the wall, Frena clawed his way out and immediately went searching for his wife. He feared the worst as he stumbled through the piles of unrecognizable rubble. Though its northern half remained standing, the violent core of the tornado had sliced through the plaza’s southern half like a wrecking ball, leveling most of the steel and concrete masonry walls. A plaza employee’s half-ton pickup sat upside-down in the wreckage, its wheels jutting out above the flattened remnants of Cashway.

The southern half of Mono Plaza was virtually obliterated.

After a few agonizing minutes, Walter Frena found his wife Rosemarie lying among a pile of bricks. Blood leaked from numerous lacerations caused by wind-borne debris, covering her face and arms and caking to her hair. She would ultimately require more than 100 stitches.

Beyond Orangeville, the tornado thundered through the Hockley Valley and traversed a rural stretch of Adjala Township, tearing up trees and power lines but encountering relatively few structures. That changed almost immediately as the twister crossed the Adjala Tecumseth Townline two miles southwest of Tottenham. Cutting across the 3rd Line at a shallow angle, it first blew through a dairy farm owned by Jack Maher.

Although he and his house were spared, that was the extent of Maher’s good fortune. His barn was totally destroyed, killing several prized Holstein cows and completely wrecking the costly milking equipment inside. A $70,000 steel silo was flattened and most of the farm equipment was totaled, including a hay wagon thrown by the wind and “twisted like plasticine.”

The vortex narrowed and gained strength as it sped along the 3rd Line, drifting gradually from the north side of the road to the south. It shattered barns and outbuildings and blew away multiple homes, flinging pieces of shrapnel in every direction. On one farm, a steel tank that had been strapped to a concrete pad was snatched up and tossed into a stand of shredded and denuded trees. A multi-ton combine on another farm was crumpled into a ball and deposited half a mile away.

Just west of Tottenham Road, Joan MacDonald’s house was torn to shreds as her mother, unable to reach the basement, clung desperately to the toilet in the bathroom. When the storm passed, virtually the entire house was gone. Incredibly, all that remained was the toilet — and her mother.

Half a mile to the east, Marjorie Webster had just pulled into her driveway when the skies opened up. She ran inside, sprinting down the hallway in the direction of her bedroom. The initial blow of the tornado jolted her off her feet, but she recovered and grasped for the bedroom door. Her ears filled with the screech of twisted tin and pried-up nails as the roof pulled apart.

The walls began to fall apart around her as she struggled to crawl along the hallway. The floor shook and pitched as if riding the wild swells of a gale at sea. Suddenly, the entire house broke loose of its moorings, shattering into pieces as it sailed through the air.

Marjorie Webster took flight along with her home, traveling well into a nearby field before tumbling out, injured but alive. She tried to stand but quickly slumped into the rain-soaked grass, lapsing into a coma from which she would not awaken for a month. Because of the severity of her injuries, Webster spent almost an entire year recovering in the hospital.

All that remained of Marjorie Webster’s home was a streak of debris.

At the intersection of the 3rd Line and 10th Side Road, two miles east of Tottenham, the tornado was again near peak intensity. A log-cabin home perched atop a small rise on the southwest corner of the intersection was “swept off its foundation and scattered.” Yvonne Rabbets, 59, was thrown hundreds of feet into the hollow behind her home and killed. Several other houses nearby were also splintered.

Less than a mile to the east, 66-year-old Jack Oldfield was busy tinkering in his workshop, oblivious to the approaching storm. A few hundred yards away, his daughter-in-law Jane watched uneasily from her window as thick clouds turned the afternoon into an opaque twilight. She considered warning her father-in-law but thought better of interrupting him; surely it was only the product of an overactive imagination.

Before the thought had even left her head, blistering winds lashed the window with sheets of rain, rattling the glass against the frame. A frightful, high-pitched keening announced itself above the whooshing gusts and staccato static of raindrops. The sound was unlike anything she’d ever heard, but she understood at once what it meant.

It all happened so quickly that she barely had time to step back and crouch down to protect herself. Within seconds, the madness outside stilled and the shrieking winds were gone. Jane waited a few moments before cautiously approaching the window and peering out across the field, scanning for the familiar outline of her father-in-law’s workshop. It wasn’t there.

She bolted out the door and ran toward the workshop, or at least the place where it had been. Now, all that remained was a jagged heap of timbers and metal and ruined equipment. Jack Oldfield lay motionless beneath it all. Neighbors quickly streamed in to help pull Oldfield from the rubble, loading him into the back of a pickup and racing to the hospital, but he succumbed to his injuries soon after arriving.

In the little community of Dunkerron, a few miles east-northeast of the Oldfield property, the tornado sliced through a pair of farms belonging to Harold and Ron Hirons. It destroyed five large barns between the two farmsteads, wrecking machinery and killing a cow and a donkey. Ron Hirons’ home suffered considerable damage, but the destructive winds just missed his father’s large brick house nearby.

Just across Highway 27, the twister cut down an entire row of homes like a buzzsaw. Two houses were reportedly swept away, leaving “just the foundations sitting there.” Others avoided a direct hit but still suffered significant damage. Cars and trucks were rolled, thrown and bombarded by debris impacts, leaving them battered and wrecked.

The storm abruptly shifted northward as it crossed Highway 400, chewing up hundreds of mature willow trees along Canal Road before plunging into the Holland Marsh. The resulting destruction was extensive. Dozens of warehouses, greenhouses, barns and other outbuildings were flattened across the vital agricultural region.

Hardest hit was the area along Fraser Street, later renamed Tornado Drive. Utility poles were shattered and toppled. Storage bins, vehicles and pieces of farm equipment were lofted or rolled along the ground. Acres of crops were mowed down, the fertile fields littered with shingles and lumber and crumpled strips of sheet metal.

The storm’s intensity finally began to wane as it entered York Region, causing moderate damage to homes along Dufferin Street in Ansnorveldt. The damage path gradually became broader and more diffuse as it passed through the south side of Holland Landing and the north side of East Gwillimbury, ripping roofs off houses, shattering windows and toppling a few unanchored outbuildings.

Video from the Holland Marsh area. (Courtesy of Jim Culbert)

The Grand Valley tornado finally dissipated near Mount Albert at 5:31 pm, some 76 minutes after it began. In that time, it covered more ground than any known tornado in Canadian history, tracking just under 70 miles at an average forward speed of 55 mph. It produced violent damage and claimed lives in multiple communities, yet this record-breaking twister was soon to be overshadowed by the monstrous storm looming just 20 miles to the north.

Lisle, ON F2

As the historic storm to its south was ripping through Grand Valley, the northern supercell was wasting no time in reloading. The Corbetton tornado was still roping out when a new vortex formed immediately to the southeast. Beginning just below the bluffs outside of Ruskview, it promptly began flattening and uprooting trees along County Road 21.

Hacking and slashing a trail through the densely wooded countryside, the tornado produced a “considerable swath of destruction.” It dipped south of Randwick before drifting slightly northward as it neared the Simcoe County line, leaving few trees standing in its path. Missing the tiny community of Airlie, it then clipped the south side of Lisle, causing significant damage to two properties.

Beyond Lisle, the twister entered the historic grounds of CFB Borden, the Canadian military’s largest training base and the birthplace of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Disaster was averted, however, when the funnel rapidly dissipated and the supercell once again began to cycle.

The narrow escape would soon prove fortuitous in more ways than one as base officials began receiving urgent calls for help from the region’s largest population center — just 11 miles away.

Barrie, ON F4

Having already produced a trio of significant tornadoes and a near-continuous damage path spanning some 40 miles, the prolific northern supercell geared up to deliver a coup de grâce as it pulled away from CFB Borden. A new updraft base quickly formed immediately to the northeast, its broad circulation beginning to stretch and tighten. For the people of Barrie, a thriving city of more than 40,000 on the western shore of Kempenfelt Bay, the timing couldn’t have been worse.

A few miles southwest of downtown, the static thrum of rain drew Evelyn Fisher’s attention. Fat drops swirled through an open window nearby and spattered on the kitchen floor. Dismayed by the growing puddle, she hurried off to the laundry room to fetch a rag.

Outside the laundry room window, movement flashed across the edge of her peripheral vision. Peering out across County Road 27, she spied a “swirling gray mass” heading in her direction. She ducked behind a set of cupboards and covered her head as the laundry room door slammed shut and windows began crashing in around her.

Once the commotion had stopped, Fisher slowly made her way to the door. She was puzzled to find soggy batts of insulation strewn across the floor, but the cause quickly became evident. Most of the roof was gone, ripped up in sections and flung hundreds of yards away. Little remained of the kitchen. A barn across the road was “taken out,” its contents blown into the Fishers’ yard.

Barely a minute after touching down, the tornado was already becoming ferociously destructive. It moved along the north side of Ardagh Road, tearing a gash more than 500 yards wide through a pine forest plantation. Hundreds of trees snapped like toothpicks, their bark peeled away by the wind and debris. Where the forest thinned out, a narrow strip of scoured ground marked the sinuous path of the vortex core.

In a small, tree-lined residential neighborhood between Crawford Street and Patterson Road, eight-year-old Nicki Lefebvre was playing a game of hangman with her neighbor and best friend, Paula Bodenham. Nearby, her mother Patricia watched the deteriorating weather through the window with growing apprehension. When the local paperboy stopped to make his daily delivery, Patricia urged him to head home right away.

As a gusty squall blew through the subdivision, she called the boy’s mother and was relieved to learn that he’d arrived safely. Before she could replace the handset, a blast wave of wind and debris exploded through the kitchen. The entire Lefebvre home was shattered and swept from its foundation, throwing Patricia and her five-year-old son Danny 200 yards to their deaths.

Nicki Lefebvre was gravely injured and spent two weeks in a coma, while her friend Paula was killed. Just down the street, the Bodenham home was torn apart and scattered. Paula’s parents and young brother were ejected from the wreckage but survived. Another neighbor did not. Todd Wilson, 13, was fatally injured when his family’s home was demolished.

The tornado was nearing the crescendo of its calamitous power as it swept through the outskirts of Barrie in near-F5 fashion. Vehicles were hurled hundreds of yards and crushed or twisted around trees, some of them stripped to their bare frames. Homes disappeared in the blink of an eye, transforming into a sea of fragmented debris.

Wilhelmina Schoneveld, 66, was at her kitchen table chatting with a relative from Holland when her two-story house at the corner of Patterson Road and Patterson Place was “reduced to splinters and sawdust,” killing her instantly. A few doors down, Natalie and Verne Ferrier were in their garage visiting with friends when the entire structure suddenly blew away. Verne was struck by a plow and Natalie was buried under broken trees, but the Ferriers and their friends managed to escape with their lives.

For most of the workers in the Morrow Road industrial park, the weekend came unexpectedly early. Widespread grid damage caused by the tornado near Orangeville had cut power to the area half an hour earlier, leading many plants to shut down and send their employees home. Fuzzy sunlight shone through a hazy veil of cloud as hundreds of people streamed out of the area, winding their way toward the nearby Highway 400 interchange.

One of the few people heading in the opposite direction was Bill Vandeburgt, owner of Barrie Retreading Ltd. He’d set out to do some banking downtown, but the citywide power failure cut his trip short. As the industrial park emptied, he returned to his office in a low, squat building on the west side of Morrow Road.

Despite the power outage, Bill was in no hurry to leave. Instead, he sat in the quiet office and chatted with his son David. A bright and mischievous young man with a penchant for pranks and practical jokes, David Vandeburgt had just celebrated his 27th birthday with friends and family the previous evening.

A few minutes past 5 pm, a murky gloom fell over the industrial park. Heavy squalls followed, peppering the roof with torrential rain and hail. When a deep, gravelly roar rose up outside the shop, David darted for the door to check on the commotion.

“Holy shit Dad, it’s coming right at us!”

No sooner had the words left his lips than David was gone, borne away by winds of almost unfathomable violence. In the same instant, a terrific blow knocked Bill Vandeburgt from his chair. He tumbled like a ragdoll, crashing into one wall after another as Barrie Retreading began to disintegrate. Suddenly, he came to a halt as he collided with a large, heavy object, knocking him unconscious.

Not far away, the windows at the Atlas Auto Supply Company rattled loudly in their frames. Owner Ron McKittrick, who’d stayed behind in the office with another man to finish up some business, cautiously reached for the nearest window to stop the vibration. When the entire building began to shudder, the two men hit the deck and flattened themselves against the floor.

Within seconds, the tornado leveled the Atlas warehouse with a deafening blast. Thundering winds toppled brick walls and shredded roof panels. The two-inch structural steel columns supporting the bulk of the building warped and twisted like twist ties.

When Bill Vandeburgt regained consciousness, he found himself lodged between a gas meter and a compressor bolted to the concrete slab — among the few things remaining of Barrie Retreading. Though dazed and disoriented, he immediately began combing through the rubble in search of his son. Others soon arrived to join in, but there was no sign of David.

Just down the street, Ron McKittrick surveyed his surroundings in disbelief. Had the power outage not sent his employees home for the day a half-hour earlier, they’d have surely been buried under the tons of rubble occupying the former site of the Atlas Auto Supply warehouse. As it was, the office in which he and another man sought shelter was the only section of the facility left standing.

Outside, Ron’s prized Mercury Cougar — purchased just two months earlier — was sitting in a crumpled ball hundreds of yards away. Semi-trailers were smashed together and “tossed like children’s toys.” Heavy manufacturing equipment was torn apart and strewn about in pieces.

In all, nearly a dozen factories and shops in the Morrow Road industrial park were totally destroyed. Several others along the edges of the path were still standing but heavily damaged, as was the city’s Masonic Lodge at the northern end of the street. Near the center of the track, the winds were so violent that they drove splinters of wood into concrete and left a steel brake drum practically folded in half.

Some of the worst devastation occurred at the Albarrie textile plant. The large industrial building was utterly demolished, leaving behind an unrecognizable heap of shattered brick walls, mangled steel beams and ruined machinery. Amid the wreckage, first responders found the unidentified body of a young man clad in work clothes.

Tragically, the victim was later identified as David Vandeburgt. His head had struck a steel door frame when he was sucked into the tornado, killing him instantly. Ultimately, he’d been carried more than 1,000 feet from his original location.

Still at peak intensity as it exited the industrial park, the tornado plowed across the northern end of the Highway 400 interchange. Vehicles were blown off the road and bombarded with bursts of high-velocity shrapnel. Steel guardrails were ripped out of the ground and clumps of grass were scoured from the embankments flanking the elevated roadway. Even hardy, low-lying shrubs were completely debarked and shredded, indicating extreme near-surface winds.

Clark Priester, a 46-year-old surgeon, was driving north on the highway when he noticed what seemed to be a heavy rain squall coming from the west. Looking closer, he could see chunks of wood and strips of sheet metal “fluttering through the air like tinsel.” As he contemplated the unusual sight, several things suddenly happened in rapid succession.

A pitch-black darkness washed over the highway, followed by a frightful roar. All at once, a massive jolt shattered the windows and sent Priester’s Buick pinwheeling through the air. He blacked out, but only briefly, awaking to find that his car had improbably come to rest on all four wheels. Though it was smashed far beyond repair, he was able to force open the driver’s door and escape.

Stopping momentarily to take stock of the situation, he became vaguely aware of a warm trickle flowing from the right side of his head. Blood seeped from a gash in his scalp, running down his neck and onto his shirt. Bits of glass and metal had pockmarked his opposite shoulder like birdshot.

All around him, Highway 400 suddenly looked like a warzone. Dozens of people lay strewn in bloody heaps across the roadway and down the embankment. Others wandered aimlessly in shock. Gathering his wits, Priester quickly drew on his medical training and set about rendering aid until first responders arrived. Ultimately, although many commuters were injured — some very seriously — no motorists on the highway were killed.

At the popular Barrie Raceway, wedged between Highway 400 and Essa Road, racing horses ran frantically in all directions as the air filled with debris. Destructive winds raked the grounds as the core of the twister passed narrowly to the south, flattening barns, tossing horse trailers and badly damaging a grandstand. Stables blew away in their entirety, plastering anything left standing downstream in a thick layer of mud and manure.

A pickup truck parked outside one of the horse barns was “tossed like a dinky toy” and nearly crushed flat as it landed 400 yards away. Luke Tremblay, 27, was sitting in his car in the nearby raceway parking lot when it, too, was snatched up by the winds. He was ejected from the car as it tumbled away, suffering grave injuries to which he later succumbed.

The funnel began to contract and move eastward as it crossed Essa Road, damaging the Barrie Curling Club and several other structures. Climbing a small rise into Allandale Heights, the tornado sheared off the upper floors of an entire townhouse complex on Adelaide Street and leveled sections of it to the ground. Homes along Debra Crescent and Innisfil Street were also hit hard.

One home in this area was nearly flattened when the crumpled sleeper cab of a semi truck smashed through its roof. The cab was believed to have been torn from a truck in the vicinity of the highway — a distance of nearly half a mile.

The still-shrinking vortex seemed to lash out randomly as it followed Murray Street up yet another slope. Dozens of homes were struck, with impacts ranging from roof and siding damage to near-total destruction. The hit-or-miss damage pattern continued along Joanne Court, Springhome Road and Tower Crescent. By the time it crossed Woodcrest Road, the track was just 150 yards wide.

As it raced eastward along Greenfield Avenue, however, the tornado once again surged in intensity. In the nearby Trillium Crescent subdivision, 12-year-old Crystal Poechman was sitting in her kitchen watching black specks fly and swirl through the air. She wondered whether she was seeing a flock of birds, but her father knew better — “It’s a tornado, get downstairs!”

The roar was nearly deafening. When it passed, Crystal and her father emerged to find the new subdivision around them in ruins. The air reverberated with screams and cries and piercing sirens. The Poechmans’ own home had been saved, but their relief was quickly replaced by a chilling realization: Crystal’s younger brother had been away from home when the storm hit.

Nine-year-old Jonathan Poechman was fishing with a group of friends at Brentwood Marina when storm clouds began rolling through. As he was always told, he jumped on his bike and headed for home as soon as it started raining. Though his friends took shelter with a trusted neighbor, Jonathan continued pedaling on toward Autumn Lane.

Sadly, the young boy never made it home. Only minutes from his destination, he was overtaken by the storm and killed by flying debris, becoming the tornado’s eighth and final victim.

Just to the east, an already devastating situation very nearly became an unthinkable calamity. The tornado savaged a small industrial park on the west side of Highway 11 — now known as Yonge Street — ripping apart a row of warehouses and storage facilities. One of the demolished properties was a propane distributor with several large, fully-loaded storage tanks on-site.

When the powerful vortex swept through, it snatched up a school bus and hurled it into the industrial park. The battered bus landed with a crunch and came to rest among the propane tanks, missing several of them by a matter of feet. A direct impact likely would have ruptured the tanks, violently depressurizing the liquefied gas inside and triggering a catastrophic boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE). In such an explosion, fire officials estimated that the resulting blast wave and aerosol fireball may have reached a mile in diameter.

This bus only narrowly avoided triggering a horrific explosion.

Crossing the railroad tracks east of the highway, the funnel again reached a width of a quarter-mile. It cut through the Tollendal Woods subdivison, causing moderate damage and snapping swaths of trees. The final recorded damage came on the shores of Kempenfelt Bay, where it tossed around boats and wrecked several structures at the Brentwood Marina.

Although the official path of the Barrie tornado ends at the shoreline, witness reports suggest the tempest may have continued well out into Kempenfelt Bay as a tornadic waterspout. The waterspout may have traveled up to four miles over the water before finally dissipating south of Shanty Bay.

Tornado Watch #211

Two hundred miles south of Barrie, the mood was growing tense inside the National Weather Service office in Cleveland. Though not yet aware of the carnage unfolding north of the border, the forecasters were seeing worrying signs much closer to home. Standing at the window, Jack May watched a bulging cumulonimbus tower rise like a mushroom cloud, its buoyant energy propelling it tens of thousands of feet into the atmosphere.

It had been less than 90 minutes since the National Severe Storms Forecast Center issued its afternoon severe weather update, making the fateful decision to downgrade the region to a Slight Risk. Local forecast offices had no more than received and reviewed the outlook before the first thunderstorm flared to life in Northeast Ohio. Another soon followed. And then another.

As it happened, Jack May was far from the only weather official feeling apprehensive. At the NSSFC in Kansas City, lead forecaster Steve Weiss monitored the incoming satellite imagery with growing alarm, watching as storm cells began exploding like popcorn kernels. His stomach tightened into knots.

Even days in advance, the forecasters at the NSSFC had rightly recognized the large-scale patterns of a dangerous outbreak. What they hadn’t seen in the moment — what the limited tools and technologies of the day hadn’t revealed to them — was the intricate dynamics coming together to create something approaching a worst-case scenario.

Throughout the day, abundant sunshine had steadily heated the atmosphere until it roiled with energy. Temperatures along the Ohio-Pennsylvania border surged by 10 degrees or more in less than two hours. Strong southerly flow acted like a pipeline for steamy tropical air, injecting atmospheric jet fuel into an already combustible environment.

Atmospheric instability is most commonly expressed by Convective Available Potential Energy (CAPE), which essentially measures the amount of energy available to any storms that might form. CAPE values of 1,000 j/kg or more indicate moderate instability and are usually sufficient for strong to severe thunderstorms. Readings of 2,500 j/kg or more suggest a highly unstable atmosphere, supportive of powerful updrafts and intense storms.

Across eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania, afternoon CAPE values soared to 3,500 j/kg or more. The bubbling pot seemed poised to boil over at any moment, yet the elevated mixed layer — blown in from the superheated Desert Southwest — remained clamped over the region like a giant lid.

CAPE values at 5pm on May 31 indicate an exceedingly unstable atmosphere.

To forecasters, the resulting lack of thunderstorm development outside of Southern Ontario seemed a reason for optimism. Perhaps some crucial, unseen ingredient was missing. Perhaps the lid was strong enough to suffocate the would-be outbreak before it began.

In reality, however, the clear skies simply allowed the atmosphere to continue simmering like a pressure cooker, waiting for a trigger to release its pent-up fury.

For the people of Ohio and Pennsylvania, that trigger arrived at the worst possible time. Around 4 pm, the shortwave trough swinging through the Upper Midwest began pushing into the Great Lakes. An intense mid-level jet streak at its base provided ample wind shear and lift, priming the atmosphere for convection. A subtle split in the jet streak created diffluent flow directly above the region, further enhancing upward motion.

Just ahead of the trough, the EML that had been suppressing convection across the area continued its slow eastward migration. As the edge of the mixed layer slipped away, the rising motion in the atmosphere effectively lifted the lid, releasing the explosive airmass below. Plumes of hot, moisture-laden air rushed out from beneath it, surging high into the troposphere. In the blink of an eye, multiple vigorous updrafts filled the skies over northeastern Ohio with clusters of towering cumulonimbus clouds.

Analysis showing the edge of the lid (double solid line) at 8pm May 31. (Adapted from Farrell 1989)

It was these bright, cauliflower-shaped thunderheads that Jack May watched from his window at the National Weather Service office, but his perch afforded only a limited view of the larger picture. In Kansas City, the satellite data streaming into the NSSFC offices left no doubt. The fuse had been lit — the powder keg was about to explode.

After conferring with local weather offices in Cleveland and Buffalo, Steve Weiss quickly issued Tornado Watch #211.

BULLETIN–IMMEDIATE BROADCAST REQUESTED

TORNADO WATCH NUMBER 211

4:25 PM EDT FRI MAY 31 1985

A…THE NATIONAL SEVERE STORMS FORECAST CENTER HAS ISSUED A TORNADO WATCH FOR

PORTIONS OF EASTERN OHIO

PORTIONS OF THE NORTHERN PANHANDLE. W. VA

PORTIONS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA

PARTS OF SOUTHWEST NEW YORK

PORTIONS OF CENTRAL AND EASTERN LAKE ERIE

SOUTHERN LAKE ONTARIO

FROM 500 PM EDT UNTIL 1100 PM THIS FRIDAY AFTERNOON AND EVENING

B…TORNADOES…LARGE HAIL…DANGEROUS LIGHTNING AND DAMAGING THUNDERSTORM WINDS ARE POSSIBLE IN THESE AREAS. THE TORNADO WATCH IS ALONG AND 70 STATUTE MILES SOUTHWEST OF AKRON OHIO TO 20 MILES SOUTH OF ROCHESTER NEW YORK.

REMEMBER…A TORNADO WATCH MEANS CONDITIONS ARE FAVORABLE FOR TORNADOES AND SEVERE THUNDERSTORMS IN AND CLOSE TO THE WATCH AREA.

PERSONS IN THESE AREAS SHOULD BE ON THE LOOKOUT FOR THREATENING WEATHER CONDITIONS AND LISTEN FOR LATER STATEMENTS AND POSSIBLE WARNINGS.

…WEISS

Albion, PA F4

Greg Galloway hadn’t thought much of the tornado watch when it blared from his truck radio, but he knew trouble when he saw it. As the 22-year-old warehouse worker and his girlfriend drove north toward Monroe Center, a tiny town about a mile from the Pennsylvania border in Ashtabula County, Ohio, the whole sky seemed in turmoil. Thick, carbonous clouds swelled and churned ahead of them, spiraling into a central updraft like a massive gyre. The whirling bolus dipped low, sagging below the cloud base as if being sucked down a drain into the earth.

Surrounded by flat farmland, Galloway and his companion were afforded an excellent view of the storm. A succession of faint, ephemeral funnels formed, dissipated and reformed beneath the lowering wall cloud. After several false starts, the young couple watched as the transient funnel cloud suddenly took root a mile southeast of Monroe Center.

Almost instantaneously, a dark, well-defined cone began mowing through a stand of trees along Hilldom Road. Utility poles broke loose and toppled, showering the road with sparks. Power lines snapped like flailing whips. Hastening across Middle Road, the vortex flipped several mobile homes into the air and scattered them hundreds of feet. At a nearby farm, it picked up pieces of machinery and tossed them into a field.

Rushing off to the northeast at nearly 50 mph, the storm entered Pennsylvania in the extreme northwestern corner of Crawford County. It surged across Joiner Road, blowing a pair of houses off their foundations before crossing into Erie County. There, the tornado cut a swath up to half a mile wide through a dense patch of forest known locally as Jumbo Woods, splintering hundreds of beeches and sugar maples.

From his home in southern Conneaut Township, 40-year-old Richard Bomboy studied the tumultuous western sky with deep concern. Despite being paralyzed in a workplace accident a few years prior, Bomboy was an active and experienced Skywarn storm spotter. He often called in valuable reports during foul weather, using a 180-degree video camera affixed to a high-gain directional antenna to scan from horizon to horizon.

A little after 5 pm, Bomboy’s intuitive sense of foreboding proved correct. As the supercell emerged from Jumbo Woods and came into view of his tower-mounted camera, he spied a broad, dark wall cloud descending from its rear flank. A ragged funnel hung beneath it, surrounded by a sheath of dust and seemingly scraping along the tops of the trees.

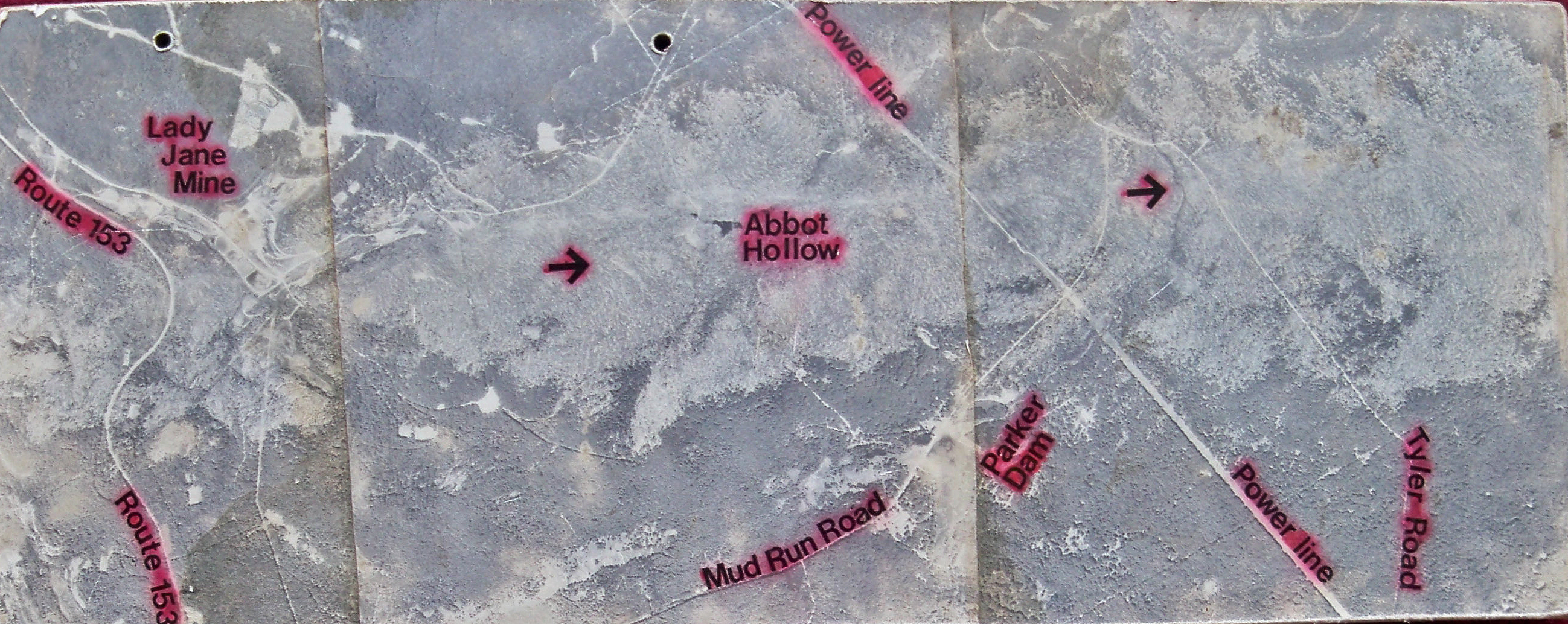

The tornado left a clear scar through Jumbo Woods on satellite.

Inside the heart of the tornado, shrouded in the pulverized remains of trees and vehicles and houses, a metamorphosis was taking place. Driven by extremely low pressure, an intense downdraft began to punch through the core. Surging outward as it neared the ground, the downdraft clashed with the violent low-level circulation, splitting the vortex and spinning up multiple subvortices — small, individual mini-tornadoes rotating at high speeds within the broader flow.

The sight was mesmerizing, but Bomboy had no time to watch. Grabbing the radio, he reported his sighting to the local National Weather Service office in Erie: “Just spotted a tornado touchdown about five miles west of Albion. Actually, I see at least two of ‘em forming. They’re headed directly toward Albion.”

Nestled into bucolic farmlands 20 miles southwest of Erie, Albion was a quiet and peaceful town of about 1,800 in 1985. Though it was near the peak of a modest population boom, the town had fallen on hard times. The Bessemer & Lake Erie Railroad, Albion’s largest employer, had pulled up stakes and shuttered the local freight yard two years earlier, eliminating nearly 300 railroad jobs. Few other opportunities popped up to replace them.

Despite its misfortune, the community remained tight-knit and resilient. Not many people ever left Albion, if only because not many wanted to. Even in poor soil, family roots often run deep. Still, in a place whose only claim to fame was the excellent steelhead and muskie fishing supplied by Conneaut Creek — the spidering branches of which meander along the periphery of the borough — it was easy to believe that nothing ever really happened.

And so, when a tornado watch began popping up on television screens across town on a hot and sunny Friday afternoon, few people paid it any mind. The area had seen bad weather on occasion, of course, but a tornado? That wasn’t the kind of thing that happened in Albion.

Fire Chief Herk Shearer felt much the same way, at least until his emergency radio suddenly crackled to life with an urgent call from the station. After alerting the Erie weather office, Richard Bomboy had called the Albion Volunteer Fire Department to report that a tornado was headed their way. Moments later, a woman called to report that she’d witnessed “three tornadoes” — likely the twister’s multiple vortices — heading northeast and doing damage just beyond Jumbo Woods.

All across Albion, the call went out for firefighters to report to the fire hall immediately.

A few miles southwest of town, Jim and Bunny Reighard were sitting down to enjoy a pizza with their children. Before they could dig in, however, the floor of their two-story farmhouse began to vibrate. A deep, plangent roar reverberated the air, seeming to come from nowhere and everywhere at once.

The peculiar sensation defied ordinary experience, like being buzzed by a succession of low-flying jets on a bombing run. Unnerved, the Reighards quickly grabbed their children and led them toward the cellar steps. They reached the bottom just as the first-floor windows blew out.

On the other side of Knapp Road, Teresa Heaton had seen the monster coming as it climbed a small hill in the distance. Her first thought was for her mother, 78-year-old Lydia Taylor, who lived in a trailer a few yards away. With no place to take shelter, she knew the only chance of survival was to flee.

Heaton sprinted for her car and rushed to pick up her mother as the storm stalked over the hill and through the field. Hesitating briefly, she ran back inside to grab a flashlight. She returned only moments later, but it was already too late.

Just up the road, another neighbor had spotted the pulsating funnel as well. Debbie Sherman, 24, was arriving home from her factory job in Edinboro when she spied the infernal whirlwind above the distant treeline. She dashed inside to pick up her beloved dog, clambered behind the wheel of her van and gunned the engine.

Nearly a third of a mile wide and moving at 45 mph, the tornado tore through several properties along Carter Road before bearing down on Teresa Heaton and her mother. The churning debris cloud enveloped them in a sudden, impenetrable darkness, the chewed-up remains of houses and barns and trees and scoured fields battering the car from every angle.

Teresa clutched the steering wheel with all her might as the wind tried to pry her loose, exerting such force that the steering column began to give way. The windows shattered, peppering her body with a hail of glass fragments. The wheels of the car lost contact with the ground.

A short distance away, the Reighards scrambled for cover as their farmhouse lifted from its foundation. The sturdy two-story structure collapsed like a house of cards, filling the cellar with wind-blown debris. A floor joist struck Bunny in the head, knocking her out cold. Her daughter let out a piercing scream. Jim tried in vain to search for his family, finding it impossible to force his eyes open in the gritty, blinding wind.

At the same time, Debbie Sherman was unwittingly hurtling toward disaster. As she peeled out of her driveway onto Knapp Road, she had no idea she was driving straight into the jaws of death. A neighbor pulling his tractor into his barn recognized Sherman’s fateful trajectory and hurried to intervene, racing toward the road and frantically trying to get her attention.

To Jim Reighard, the ghastly assault seemed to stop time in its tracks. In reality, it lasted scarcely 30 seconds. When he could again open his eyes, he found his world entirely altered. The house was gone, a gaping opening the only thing remaining to mark its location.

Jim & Bunny Reighard’s home was blown away. (Courtesy of Sally Dobson)

A twisted piece of farm equipment from a neighbor’s property jutted out from the opposite end of the cellar. Trees were totally denuded, snapped off at the base or torn out by the roots and tossed across the yard. A savings book belonging to one of the Reighard children later turned up some 50 miles away in Maysville, New York. Bunny was seriously hurt, but the Reighards escaped with their lives.

The frame of Lydia Taylor’s trailer wrapped around a totally debarked tree near the Reighard property. (Courtesy of Sally Dobson)

Against all odds, so did Teresa Heaton. Although she suffered terrible injuries and lived for years with glass fragments embedded in her skin, the steering wheel of her car held her in place and likely spared her life. Sadly, her mother had no such protection. Lydia Taylor was sucked through a window and found in a shallow ditch near the crumpled car.

Despite his best efforts, Debbie Sherman’s neighbor could not arrest her fate. He watched helplessly as her van shuddered, tipped and lifted from the road, rising hundreds of feet into the air before sailing over the top of a silo. It crashed to the earth in a nearby field, instantly killing Debbie and her dog.

After a long day’s work in neighboring Springboro, Robert Koehler couldn’t help letting his thoughts drift as he followed Route 18 home to Albion. His 10th anniversary was approaching and his mind wandered as he ruminated over the perfect gift. Thoughts of fine jewelry and romantic getaways soon evaporated, however, when he fixed his eyes on the distant horizon.

The mid-afternoon sky was cloaked in low, murky clouds. Faint tinges of green and yellow flecked the storm’s bubbling base, creating an unusual and vaguely unsettling appearance. A large funnel, as dark and dingy as charcoal, hung from a lowering a few miles off to the west.

The shape-shifting mass moved like a wounded animal, surging forward erratically and recoiling before striking out again. Pulling over at the crest of a hill overlooking downtown, Koehler watched as the tornado came to a sudden halt, wobbling drunkenly in place and briefly looping back on itself before accelerating again. To his immense relief, the vortex appeared to be tearing itself apart.

But all was not as it seemed, and while the whirling cloud had shed much of its mass, it had lost none of its potency. Sporting a deceptively slimmed-down profile, it began to gently curve away from him as it picked up speed. In fact, it seemed to be following the Bessemer & Lake Erie Railroad — directly toward downtown Albion.

The tornado’s wobbly track as it approached Albion. The Bessemer & Lake Erie Railroad tracks are on the right. (Courtesy of Ipper Collens)

All at once, unseen structures began to explode, cloaking the funnel in a swirling sheath of debris stretching hundreds of feet into the air. Robert Koehler could feel his pulse pounding in his ears. A cold sweat prickled his skin and he felt ill as he muttered to no one in particular: “My God, they’re all going to die.”

About a mile to the northeast, Michael McCabe was headed back to Albion after running a few errands in neighboring Cranesville. Heavy rain began falling in torrents, pelting the family station wagon as he turned west on Route 6N with his mother and younger brother in tow. Pitch-black clouds blotted out the sun, reducing visibility even further.

Cresting a hill just east of town, the rain abruptly gave way to reveal a startling view. A broad, dark funnel hung from the clouds, splitting the opposite horizon into contrasting thirds. For a moment, the extraordinary sight seemed too overwhelming, too implausible to sink in. “Is that what I think it is?” Michael’s mother asked incredulously. The answer came from his younger brother, Sean. “Yes! It’s a tornado!”

Worse still, the powerful tempest seemed to be heading straight for the McCabes’ neighborhood. Michael thought of his grandmother, home alone and likely unaware of the impending calamity. He raced ahead into the path of the storm, throwing caution to the wind in a desperate bid to reach her before the maelstrom closed in.

The tornado was less than a mile away by the time the McCabes pulled into their driveway on East State Street. Hail ricocheted off the car and bounced across the pavement. Sean McCabe sprinted for home and dashed for the basement while Michael and his mother went to warn his grandmother of the rapidly approaching storm. Unfazed, she remained characteristically skeptical: “Well, who predicted it?”

As if on cue, a violent gust of wind whistled through the neighborhood, blowing heavy rain and hailstones almost horizontally against the side of the house. Windows began to shatter. With no time to spare, Michael lifted his grandmother and carried her down the narrow steps into the cellar.

Sweeping across the railroad tracks into the south side of town, the tornado struck Albion with phenomenal force. It swept away trailers and frame homes alike in a 300-yard swath along Main Street, Park Avenue and Jackson Avenue, injuring multiple people and killing 70-year-old Lena Keith. The savage winds smashed structures to bits and deposited the ground-up wreckage in thin, convergent streaks stretching into the nearby woodline.

On the other side of a narrow ravine, Stanley and Frances Kireta, 68 and 65 respectively, were in their kitchen when the vortex shifted sharply northward, making a beeline for their home at the southern tip of Water Street. Before they could find shelter, their house was torn from its foundation and dumped into the ravine. First responders later found their bodies strewn among the wreckage.

A few hundred yards to the east, Michael McCabe hunkered down in the cellar with his mother and grandmother. Even above the howl of wind and the pounding of rain and hail, a voice called out from the emergency scanner upstairs: “Albion Base to West County! There’s a tornado coming right through the middle of town!”

The piercing wail of the fire siren briefly cut through the din before the power failed, plunging the cellar into darkness. The only illumination came from the pale, eerie green light spilling through a small casement window. Michael felt short of breath, as if all the air were being drained from the room and pulled from his lungs. His ears popped.

The onrushing mass of wind and debris struck with the sudden force of a tsunami. The entire wall around the casement window seemed to disintegrate before his eyes. An explosion of shattered masonry and timbers knocked him off his feet and he crumpled to the ground, unconscious.

Michael McCabe awoke to the sound of his mother’s voice. He tried to move, but a tremendous weight pressed down upon him and pinned him to the cold, dank floor. A trickle of water flowed from some unknown source, pooling around his head and nearly rising to meet his nostrils. All at once, he felt certain he was going to die.

John Hosey, a volunteer fireman who lived nearby, was the first to come to the McCabes’ aid. Other neighbors soon joined in. Swinging fire axes and digging with their bare hands, the makeshift rescue crew soon freed Michael from the rubble. He’d been trapped beneath a large section of wall blown into the basement from neighbors Bob and Debbie Gould’s home when it, too, was demolished. The trickle of water had come from the Goulds’ waterbed.

Despite suffering a broken rib and lacerated liver, Michael immediately went to work helping with the ongoing rescue efforts. His mother had been pinned in a hunched position, suffering a spinal fracture that left her unable to stand up under her own power. Just beneath her, his grandmother had sustained numerous bruises, lacerations and other injuries.

A few hundred feet away, Sean McCabe emerged from the wreckage of the family’s own home largely unscathed. Many others in the area were far less fortunate. A next-door neighbor, Earl Rice, was terribly injured when a massive wall collapsed on him and crushed his legs. His wife Ruth, who’d been standing at the window when the storm hit, was blasted by shards of glass and covered in rubble.

One block to the east, 64-year-old William Revak was browsing inside J&A Auto Parts when the store began to crack and crumble. Large sections of the structure gave way, crashing down upon him and crushing him to death. Norman Elliott, 35, was visiting friends in a home next door to the auto parts store. The tornado virtually demolished it, killing him as he sought shelter.