[Click photos for larger versions.]

Note: I’m trying something a bit different with this article. I’ve added endnotes for references and comments that don’t fit in the article itself, clicking any of them will take you to the bottom of the page. Clicking on the circumflex (^) next to each number should bring you back to the appropriate spot. If you encounter any problems, please let me know.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

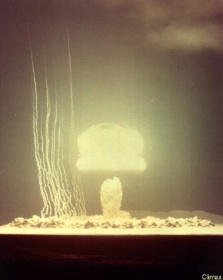

It was a time of buoyant optimism in the United States. Less than a decade after the American industrial machine first roared to life in a bid to help vanquish the Axis forces in World War II, the baby boom was well underway. Though the spectre of an apocalyptic nuclear war with the Soviet Union loomed ever-present and the Korean War continued to drag on, the country was thriving. The middle class had expanded rapidly, thanks in part to the strength of domineering unions, and consumerism and conservatism came to dominate much of American life. Scientists Francis Crick and James D. Watson prepared to unveil the double-helix structure of DNA. The first production Corvette – a sleek white convertible with red interior and a black canvas top – rolled off the production line at the iconic General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan. The manufacturer’s 50 millionth car, a golden-hued 1955 Chevy Bel Aire Sport Coupe, would be produced at the same plant in November of the following year. In December, Marilyn Monroe’s nude figure would be immortalized in the first issue of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy magazine.

The Cold War was never far from the surface, however. On the arid, sandy Yucca Flat in the eastern portion of the Nevada Test Site, the U.S. Military conducted a frenzied series of atomic bomb tests in a never-ending effort to keep a leg up on the Soviets in the developing nuclear arms race. In the predawn hours of June 4, a Convair B-36 Peacemaker rumbled down the runway at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, New Mexico and took to the dark skies 40,000 feet above the test range. As the first Air Force plane capable of delivering any nuclear device in the military’s arsenal without modifying its bomb bays, the B-36 quickly became the go-to choice for delivering a nuclear payload. As the doors to one of the plane’s bomb bays eased open, a relatively small, 30-inch fission bomb released and plummeted toward earth. At approximately 1,500 feet, a brilliant white flash and a gigantic, churning fireball burst into the sky. The bomb, codenamed “Climax” and a part of the curiously named “Operation Upshot-Knothole” series, was the most powerful ever tested on United States soil at the time, releasing a staggering 61 kilotons of explosive energy. The blast could be seen from Los Angeles and felt more than 500 miles away in Oregon, where it reportedly rattled windows and knocked items off shelves.

And despite a relatively quiet start to the year, the weather had been making the news as well. Just before 4:30pm on May 11, one of the deadliest tornadoes in the nation’s history tore a path through the heart of Waco, Texas. The six-story R.T. Dennis furniture store collapsed under the violent force of the wind, crushing 32 people inside. The same story repeated as pedestrians scurried inside several other large downtown buildings to escape the pounding rain, only to be killed when the structures gave way. Still others were crushed while trying to escape in their vehicles. When the dust settled and the victims had finally been extracted from the massive piles of rubble, 114 people had lost their lives. Another 13 were killed further to the west when more than a dozen blocks on the north side of San Angelo were obliterated by an extremely intense tornado. Though no one could have known at the time, it was about to get much, much worse.

This drawing, sketched by Truman Caldwell and completed by Waco Tribune-Herald artist Dick Boone, illustrates the tornado as Caldwell witnessed it while driving home toward the city.

June 7, 1953 was warm and muggy in Arcadia, a small outpost on the southern fringe of the rolling Sandhills region of Nebraska. Scattered rain showers and low clouds only reinforced the damp, uncomfortable conditions by the time 63-year-old Mads Madsen, his 59-year-old wife Minnie, their three children and five grandchildren sat down for Sunday dinner in the parlor just before 3:00pm. Mads had just been released from the hospital and, as was typical of the close and loving family, daughters Dolly and Mary had come to offer their support and assistance. The Madsen farmhouse, which had been remodeled earlier in the spring, stood just off Route 58 a few miles east of Arcadia. Across the road, Joy Lutz was enjoying the Sunday with her children as well. About 15 minutes later, suddenly darkening skies and gusty winds broke up the calm afternoon air. Guy Lutz glanced at the western horizon, where tremendous storm clouds seemed to be trailing a large, undulating column of smoke. Guy knew better, bursting into the house and urging his wife to “get the children and go to the cave!”

The Madsen family had a storm cave as well, but they would have no opportunity to use it. The home was ringed by a semicircle of high, broad shade trees that provided some measure of welcome relief on steamy summer days, but it’s likely the thick tree cover also prevented the family from spotting the monster approaching from the south. The house began to shake and vibrate, accompanied by a terrifying roar. The parlor burst into an explosion of glass, shards of timber and other debris as the quarter-mile-wide tornado swept the entire farmstead away. Farm equipment was tossed and crumpled like paper when the barn was blown down, animals were killed and mutilated, and the Lutz family car was thrown well over a quarter mile. The large shade trees ringing the house were debarked and shredded. Several members of the Madsen family were thrown more than half a mile, mutilated and stripped bare by the ferocious winds. All ten members and three generations of the family were killed. Farmer Lester Hubbard was also killed when his nearby home was destroyed. Although the Lutz family home was also swept away – “there wasn’t a stick of anything left in the place,” one observer recalled – no one was injured thanks to Guy’s quick reactions.

• • •

Eight hundred miles away in Central Michigan, the events in Nebraska hardly registered the following day. The school year had ended just days earlier for many area schools, leaving children anxious to begin their first week of summer vacation. After a brief overnight shower, the residents of Flint and nearby Beecher awoke to a cool, seasonable late-spring morning. There were few signs of the impending disaster that was taking shape to the west. The somewhat disorganized low pressure system that had caused the destructive tornado in Nebraska the previous day – along with at least 31 other tornadoes of varying intensity across Nebraska, Iowa and several other states, including a long-track F3 near Pomeroy, Iowa – had begun to pull itself together and deepen as it progressed through central Minnesota and toward northern Wisconsin. Overnight maps from the U.S. Weather Bureau showed strong pressure falls at many weather stations in advance of the system.

U.S. Weather Bureau surface map for June 8 at 1:30am, zoomed to the Upper Midwest. Note the strong pressure drops well in advance of the surface low. The line of cells that produced tornadoes during the afternoon of the previous day have grown upscale into a strong squall line, which is shown moving across Iowa and Missouri. Click for full map.

The low pressure system brought with it a tangled web of air masses and fronts. An occluded front extended immediately southeast of the low, just west of Lake Michigan. A warm front surged north-northeast through Indiana and Illinois, while a sharp cold front trailed back to the southwest. A deep, well-mixed boundary layer from the high elevations of the desert southwest had advected northeast and become elevated over the Great Plains. This elevated mixed layer, or EML, was clearly noted at around 700mb, an altitude of about 10,000ft, to the south and southeast of the surface cyclone. At 500mb, a closed upper-level low and attendant negatively tilted trough were migrating northeast toward northern Wisconsin in the wake of the surface low, providing enhanced upper-level divergence. Mid-level wind speeds of 50-60+ knots overspread the Great Lakes and Upper Midwest, combining with strengthening and backing near-surface winds to provide ample atmospheric rotation.

The surface map from 1:30pm on the afternoon of June 8 shows the tangle of fronts associated with the surface cyclone located near Lake Superior. This system continued to lift east-northeast during the afternoon and evening.

This map shows the 500mb geopotential heights at 6:00pm on June 8. A negatively tilted trough associated with a closed 500mb low is shown digging across the upper Great Lakes.

A reconstructed Skew-T from the Mt. Clemens sounding on June 8. Note the extreme instability (4,500+ CAPE) and veering wind profile.

By mid-afternoon, the hot, soupy air behind the warm front had begun pouring into the Great Lakes region like a burst dam. Temperatures rose into the mid- to upper-80s, while the dew point soared to 75 degrees in some areas. Big, cottony tufts of cloud popped into the blue sky like slow-motion popcorn. The EML was working its magic, creating a broad capping inversion that suppressed strong thunderstorm development to the south and allowed a steady flow of muggy air to stream into the area unchecked. At 4:00pm, Weather Bureau meteorologists at Mt. Clemens, Michigan, just northeast of Detroit, released a weather balloon and carefully studied the data recorded by the radiosonde. Although they’d been expecting strong storms for days in advance, the data was troubling. The atmosphere had become extremely unstable, and strong, deep wind shear was in place to support potentially violent supercells. Despite the poor state of meteorology at the time, forecasters recognized the ominous signs. Severe Weather Bulletin #27 would be issued just before 7:30pm, advising of the increasing threat for severe thunderstorms and an isolated tornado. The bulletin highlighted a rectangular risk area of approximately 45,000 square miles, centered around Lake Erie, with the primary tornado threat extending roughly from Pontiac, Michigan to Ashtabula, Ohio. In an era before social media and mass communication, however, few were aware that a devastating tornado outbreak was already underway.

Issued at around 7:30pm, Severe Weather Bulletin #27 outlined the expected severe thunderstorm (scalloped blue box) and tornado (red box) risk areas. Flint, designated as FNT, was outside of the tornado box but well inside the severe thunderstorm threat area.

• • •

Willis Roberts was growing restless. The Detroit-to-Pittsburgh train, already running late when it arrived at approximately 6:15, seemed to take forever to depart the station and begin the trip home. The train lurched and trundled forward, moving southwest and roughly parallel to the shore of Lake Erie in southeastern Michigan. Suddenly, he was jolted back to reality by a strange sight in the southern sky. A terrific thunderhead loomed a few miles away, seemingly bubbling up into the heavens. Peals of thunder cracked and rumbled. Beneath the southwest flank of the storm, an ice cream cone-shaped funnel tore through trees and homes and everything else in its path. Willis reacted quickly, grabbing his camera and snapping a photo of the tornado as it raced east-northeastward.[1] It had touched down moments earlier just south of Temperance, causing extensive damage to about a dozen homes and throwing several vehicles from the road. At Point Place, a small peninsula just offshore, local resident John Burdo was working on his boat at the marina when he saw the storm approach. The series of photographs he captured was chilling — a malevolent black mass, like an inverted mountain, seemingly threatening to engulf the whole horizon as it approached Lake Erie from the west.

On Dean Road, just south of Temperance, 56-year-old Walter Lewis was watching after his granddaughters, six-year-old Carol and three-year-old Judith, when a sound “like a hundred railcars on a hundred trestle bridges” bore down on their home. With little time to react, Walter huddled his granddaughters in an interior room and did his best to shelter them with his own body. It was a futile attempt, as the tornado demolished the Lewis home and killed all three. They were later found amid the piles of debris, still huddled as they had been when the storm struck. The twister continued across Dean, Substation and Temperance Roads, damaging or destroying several homes and stripping trees of their bark and limbs. On U.S. 24 (Telegraph Rd.), a number of vehicles were lofted and thrown more than a hundred yards from the highway. A semi-truck was reportedly thrown 100 yards and destroyed, but the driver survived by leaping from the cab as it was being lifted. Vergeline Rush, a 33-year-old mother who left her car to seek shelter in a drainage ditch, was not so lucky. She was crushed by the tumbling trailer while trying to protect her son, who survived despite suffering a fractured skull. About a dozen more homes suffered F4 damage east of U.S. 24 before the tornado entered Lake Erie, traveling a further 30-plus miles as a massive waterspout. Had this tornado formed just half a dozen miles further south, it would have torn a devastating path through the highly populated (1953 population: ~304,000) heart of Toledo, Ohio.

The Temperance tornado was probably near peak intensity as it crossed the shoreline onto Lake Erie. Photo taken looking south from Erie Rd., just south of Luna Pier.

• • •

Shortly before 7:00pm, as the Temperance, Michigan tornado spun itself out over the waters of Lake Erie, the first twister in a destructive tornado family touched down in a wooded area near the Henry County line just northwest of Deshler, Ohio.[2] A string of rural farmhouses were damaged as the twister churned east-northeastward. The narrow tornado killed one person along Cygnet Road before ripping more than a dozen cars, trucks and semi-trailers from Route 25 and tossing them as much as 300 yards. Though the north side of Cygnet only suffered a glancing blow as the tornado expanded in size, the damage was tremendous. Homes near Water St. and Washington St. were completely flattened, a few of them swept away in possible F5 fashion. The storm next set its sights on the home of Harry and Flossie Kline, just to the northeast of town.[3] The farmhouse was completely demolished and swept away in seconds, and trees were reportedly heavily debarked and denuded. Flossie was thrown several hundred yards and killed instantly. The bodies of her four children – Jerry Lee, 14; Linda Lou, 11; Gale, 9; and Keith, 3 – were reportedly found as far away as half a mile. Harry survived despite also being thrown from the home and suffering serious injuries.

In the hamlet of Jerry City, two miles northeast of Cygnet, machinist Thomas Bascom watched the storm coming up from the west for more than ten minutes. Describing the funnel as a “long, white cloud lashing the ground,” Bascom stood mesmerized rather than seeking shelter. His neighbor’s car was thrown several hundred yards and crushed. It wasn’t until his tool shed exploded in a hail of debris that Bascom sought shelter by diving in a ditch. His home was destroyed, but he survived with relatively minor injuries. The storm continued northeast through rural Wood County, destroying a number of homes and barns and killing another two people between Jerry City and Wayne. A “steel and concrete” bridge on Bays Road was reportedly destroyed about four miles east-northeast of Jerry City.[4] Hundreds of livestock were killed, and one farm road was covered with dead pigs “as if a giant had hurled them about by their tails.” Crop losses were extensive due to the combined effect of the tornado, high straight-line winds and hail up to the size of oranges. The path jogged slightly more northward as it passed near Wayne, eventually dissipating in extreme southwestern Sandusky County.[5] The damage in and around Cygnet was so intense that state police officers initially announced they expected to find “many more fatalities” once they were able to reach the area for search and rescue operations.[6]

As the Cygnet tornado tore through rural Wood County, another tornado had begun an 18-mile path of destruction 40 miles to the east in Erie County. First spotted at 7:30pm along Strecker Rd. near the hamlet of Kimball, the tornado traveled northeast parallel to the nearby railroad line. Structural damage began near Mason Rd. and Kelley Rd., where the farm of Beatrice Cole was heavily damaged and a long stretch of trees were ripped up and thrown across the road. The track continued over rural farmland, where a string of farms suffered large crop losses and a number of barns were blown down. One child was killed south of Ceylon when their family home was destroyed, and a group of greenhouses were shattered by the debris-filled winds in this area. At least eight people were injured in one large home that was reportedly “split in half” and wrecked. Two miles south of Beulah Beach, a group of homes from Poorman Rd. to Risden Rd. were completely destroyed and several people were badly injured. The tornado damaged at least one more home east of Route 60 and a cheese factory in Axtel as it drifted east-northeast and roped out south of Vermilion.

The Ceylon tornado ropes out south of Vermilion. Photo taken by George Glendenning from Route 113 near Birmingham, facing north.

At about the same time the Ceylon tornado roped out, four more tornadoes were on the ground in Michigan. A slender funnel touched down just west of Pleasant Lake and tracked east-northeast, killing one farmer on the north shore of the lake when his home was destroyed in F3 fashion and debris was blown into his basement. Four others were injured before the tornado lifted on the outskirts of Ann Arbor. The second, larger tornado descended almost directly over the General Motors Proving Grounds between Brighton and Milford. The automotive industry’s first dedicated proving ground suffered heavy damage and nearly half a million dollars in losses, but no injuries. Four homes, five businesses and a post office were heavily damaged throughout Highland Township during the tornado’s ten-mile path. Nearly 125 miles to the north, an F3[7] tornado began causing extensive tree damage as it touched down near Sand Lake in Iosco County. The tornado almost immediately encountered a string of vacation cottages built around the area’s lakes, promptly leveling five and causing damage to half a dozen others. Arnold Anschuetz, a firefighter from Highland Park, and his wife and two sons were killed when their cabin on Island Lake was destroyed. It encountered few other structures during the rest of its 18-mile path, but severe tree damage was noted in many places. An F2 twister also touched down south of Spruce in Alcona County, destroying a number of barns and killing some livestock.

• • •

This flurry of activity was not known to the people of Beecher, an industrial sector on the north side of Flint. Residents went about their evenings, many of them arriving home from work at the automotive plants or from the few schools which were still open. On the northeast side of town, North Saginaw St. began filling up with teenagers anxious to see the Cold War propaganda piece Invasion, U.S.A. at the North Flint Drive-In Theater. Among them were 16-year-old Charles Rachor and his high school friends, Dick Wagner and Jack Murphy, driving to the theater in Dick’s father’s sharp new Buick sedan. Thirty-seven year old car salesman Paul Ginter was also driving north on Saginaw St., returning home to Mt. Morris Township with his 14-year-old son Rayford Paul. Seventeen-year-old Patty Sue Fender had just finished her first day working at the local Citizen’s Bank, a good job for which she was extremely excited. She stopped near the intersection of Saginaw & Pierson on the way home to visit her boyfriend, Leonard Brush, and to make plans to meet later in the evening at her house along Coldwater Rd. Near the intersection of Coldwater & Summit St., 26-year-old Venessa Gensel and her husband Thomas were enjoying a relaxing evening together with their four children. The television crackled and sputtered occasionally as the wind became gusty and was occasionally accompanied by a spattering of rain on the windows.

The tornado rapidly intensified as it crossed Clio Rd. and began its trek parallel to and just north of Coldwater Rd. (center).

At about 8:20pm, volunteer firefighter Ervin McIntyre noticed the wind becoming strong and stepped outside of his home on West Carpenter Rd. on the western fringe of the city. In a field just three quarters of a mile to the northwest, a churning, “dirty-looking” funnel had begun to smash trees and unroof houses along Coldwater Rd. As McIntyre hurried inside to alert the fire department, other witnesses nearby described the tornado breaking into “many smaller whirlwinds” or “fingers,” suggesting the tornado initially had a complex multivortex structure. On North Jennings Rd., about three miles after the tornado was initially spotted, farmer Chris Miller and his hired hand Luther Morse were finishing up the last of their work when Miller’s dog began barking incessantly. Picking up the dog to throw him outside, Miller spotted the large, dark funnel bearing down and yelled to Morse to seek shelter. The men laid flat and clung desperately to the ground as the tornado swept by and destroyed the barn just yards away. Both men survived with minor injuries, but Morse’s wife and adult son would be killed when their home was obliterated about a mile to the east. The storm’s first victims, however, were 24-year-old Rose Bean and 58-year-old Wesley Blight, whose homes at the intersection of Coldwater & Clio Rd. were completely destroyed as the tornado rapidly intensified. Two others were severely injured and later died when their car was blown from Clio Rd. and thrown more than 100 yards.

Two people were killed when this car was thrown 100 yards from Clio Rd. The passengers of the car in the background were injured but survived.

Five houses to the east, four members of the Gatica family were killed when their home was destroyed and swept away. Half a mile away, near the intersection of Coldwater & Neff, Pat Fender and her boyfriend Leonard Brush heard the storm approach as they relaxed on the living room couch. The windows began to shatter as the roar grew deafening. The young couple huddled together in a final loving embrace as the house disintegrated around them, tearing the carpet from the floor and throwing them into the yard. Leonard awoke moments later, badly injured and in a daze. He would recover after an extensive hospital stay, but he’d never see Patty Sue again. His injuries prevented him from leaving the hospital to attend the funeral. Dozens more were injured or killed in this area as homes were destroyed, cars were thrown from the road and trees were stripped, uprooted and sometimes thrown bodily into fields and rubble piles. At least one vehicle was stripped of its engine, wrapped around a tree and mangled so badly that it was no longer recognizable.

This home at 1242 W. Kurtz was one of many that were obliterated. Shrubs on both the left and right sides of the photo were stripped.

The tornado was just over ten minutes into its life as it crossed Detroit Street. Over the next mile and a half, the monstrous storm would unleash death and destruction on a nearly unprecedented scale. At the corner of Detroit & Coldwater, 29-year-old Harry Pendergrass tried in vain to hold the door closed against the furious wind. He and his daughter Carol were killed instantly when the home was swept away. Virtually every home on either side of Coldwater Road was obliterated. Detective Joseph Quinn, his wife, and two of his daughters were killed at the intersection of Verdun & West Kurtz. In the span of just 300 yards between Verdun and Harvard Street on the south side of Coldwater, the swirling vortex claimed three members of the Wilfred Vaughn family, Alma Yazanko and two of her children, five members of the Herschel Tuttle family, Lorne Robinson and daughter Barbara, and at least three others. More than two dozen homes were flattened, some of the debris granulated into “wood chips” in the howling winds. Moviegoers at the North Flint Drive-In had finally noticed the looming tempest, and Saginaw Street quickly clogged as many tried frantically to flee the oncoming storm. The rush to escape caused a number of traffic accidents, further obstructing the roads and leaving some to seek shelter on foot.

More than two dozen people were killed in the pictured area, spanning from Detroit St. to near Summit St. Every single one of the nearly 40 homes was completely swept clean.

Back on Coldwater Road, the devastation continued on the next block as rows of homes were blown apart and reduced to kindling, their occupants often thrown hundreds of yards, caked with mud and left unrecognizable by the tremendous force. The family of Thomas and Venessa Gensel, finally hearing the thunderous rumble as it approached, had little time to react before they were violently thrown from their disintegrating home. Of the six family members, only Thomas survived. Mr. and Mrs. Dudley Willey were thrown several hundred yards and fatally injured, as were Frances Hutson and two children. Neighbors Kathryn Hill and Carmen Hernandez were killed, and the Kilgore family lost four members when their house was “exploded to atoms.” Dozens of vehicles were still trying to evacuate from the drive-in theater – which, in a cruel twist of fate, was on the northern edge of the damage path and suffered only minor damage – when the tornado thundered east across Saginaw St. A few lucky cars escaped at high speed, while others were tossed and rolled into trees, utility poles and the remains of homes and businesses.

Labeled at bottom center are the Kilgore (1) and Hutson (2) homes, where a total of seven people lost their lives. A multivortex structure left some homes only lightly damaged, while many others were completely demolished. The intersection of Coldwater & Saginaw is at top left.

One of many mangled vehicles, this truck lost its engine and was wrapped around a tree near the intersection of Coldwater & Saginaw. In the background, police searched a field for bodies.

Despite their best efforts, neither Charles Rachor and his friends nor Paul Ginter and his son Rayford Paul were able to evade the whirlwind. Rachor’s friend Dick Wagner, the driver, is stuck at the intersection of Saginaw & Coldwater as other motorists begin “smashing into each other like a demolition derby.” The windows blew out and the car was tossed and rolled 100 yards as the tornado struck. Paul Ginter and his son abandoned their convertible as it was thrown from the road, clinging tightly to a utility pole as the debris-choked wind savagely tore at them. The utility pole snapped just above ground level, sending Rayford hurtling into the raging tempest. Paul was gravely injured, bleeding profusely from an arm and a leg which he would later lose. He would be rushed to Hurley Hospital once the storm had passed, where he would eventually be put on an isolation floor for the several victims suffering from gas gangrene caused by the tornado. He’d share a room with Charles Rachor, who survived along with both his friends. Rayford Paul’s body was later found several hundred yards from his father’s convertible. Several others, many of them young people fleeing the drive-in, also fell victim to the tornado in this area.

Looking northeast from near East Humphrey Avenue, the path of absolute devastation is apparent. The tornado traveled from top left to bottom right along Coldwater Road.

At a service station just east of Saginaw Street, gas gushed from pipes where pumps were ripped from the ground. The Beecher Lumber Company burst apart. Sixty-year-old Nora Kane and her son John were flung to their deaths when her home was engulfed by the vortex. Alice Hedger and two daughters were killed, as were Robert Parr, a daughter and a son, as well as Shirley Harger and her ten-month-old daughter Lorraine. Home after home was shattered and blown away, exposing those inside to raging winds that may well have exceeded 250 miles per hour. Some of the victims were so battered and mangled that they were difficult for family to identify and for search and rescue workers to accurately count. The few trees that were left standing were often stripped bare and blasted with a coating of mud, described by one survivor as looking like “the aftermath of a forest fire.” One man in this area was impaled by a 2×4 so long that it had to be cut on both sides before he could be loaded into a car and rushed to the hospital. After tearing a seven-mile path through the north side of Beecher, the tornado crossed North Dort Highway and moved east-northeast into sparsely populated farmland. What may be the final fatality occurred just to the east along Branch Road, where 62-year-old George Morris was killed when his house was blown apart.

The tornado destroyed dozens of other homes, barns and other structures as it churned east-northeastward toward the Lapeer County line, growing to a maximum width of about half a mile. A home was destroyed and two people injured just east of Holloway Reservoir. Passing just south of Columbiaville, the tornado next set its sights on the farm of Everett Sheffer just north of Mt. Morris Road. Everett’s son Rick, then four years old, recalls visiting in the dining room with his mother, Genevieve, sisters Connie and Cheryl, Aunt Dorothy and cousin Sue when the wind began to come in quick, strong gusts. Moments later, the lights flickered and went out. Genevieve called for the family to head to the basement just as the windows began to shatter. Everett Sheffer and his brother Maurice had seen the storm coming and were running to warn their families when it struck. The house, barn and other buildings were destroyed in seconds, just as the family in the house reached the safety of the basement. Everett was struck in the back of the head by a flying beam and knocked unconscious, but everyone survived. The nearby home of Harold Leach was reduced to a slab. The family had run toward a neighbor who had a basement, but the storm caught them in an open field. All four family members were picked up and blown some distance, but there were no fatalities. Finally, after another seven miles and a dozen more structures destroyed, the tornado sputtered and roped out just east of Fish Lake Road in central Lapeer County.

This photograph, taken as part of an insurance advertisement, shows young Rick Sheffer standing in front of the ruins of his home with his mother Genevieve.

The devastating Beecher tornado killed 116 people across its 29-mile path[8], all but three of the fatalities coming in a three-and-a-half mile stretch roughly bounded by Clio Road and North Dort Highway. Rarely has a tornado caused such a concentrated loss of life, with nearly two dozen families suffering the loss of multiple members and five families losing four or more. In the worst-affected areas, rescuers sometimes arrived to find more than a dozen bodies strewn throughout nearby fields and other open areas, some of them a few hundred yards from where they originated. Strangely, members of the same family were sometimes thrown in opposite directions. Detroit Police Commissioner Donald Leonard said of this area, “it was worse than anything I saw during the ‘Blitz’ in London,” referring to the crippling German bombing campaign during World War II. Debris from the Beecher area would later be found across the Canadian border in North Middlesex, Ontario – more than 100 miles away.

An aerial view of Coldwater Road, looking west, shows the extraordinary intensity of the narrow damage path. The North Flint Drive-In can be seen in the upper right corner.

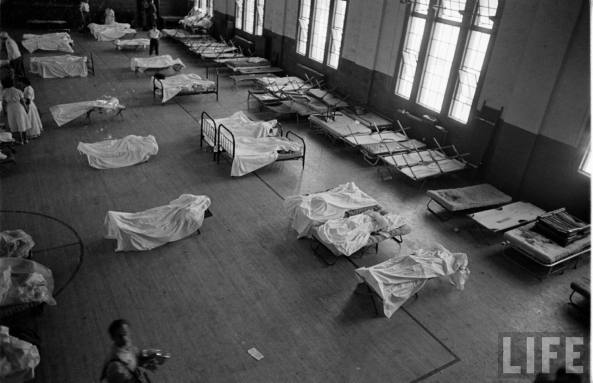

At the National Guard Armory on Lewis Street in Flint, opened to serve as a temporary morgue, the initial period after the event was relatively quiet. Within about half an hour, the quiet sense of foreboding gave way to chaos. Volunteers poured through the doors in a steady stream, carrying bodies in to await identification. Trucks pulled up and unloaded still more bodies, sometimes half a dozen at once. Volunteers trailed closely behind, mopping up the trails of blood and doing their best to clean the victims. Family members made their way in to check for loved ones: some of them quietly despondent, others inconsolable. For many, the sheer scale of the disaster was overwhelming. A profound sense of shock was painted on nearly every face. To the north a flood of vehicles, some of them hardly operable after being buffeted by the storm, carried the hundreds of wounded to area hospitals. For the line of supercells marching across the Great Lakes, however, the night was not yet over.

The National Guard armory, turned into a makeshift morgue, was the scene of much heartbreak when survivors gathered to identify the dead.

• • •

In June of 1953, the recently instituted practice of issuing tornado warnings was still very much a work in progress. The criteria for issuing a warning varied from office to office, and many still hadn’t issued a single one. Indeed, some offices still maintained that it was a bad idea, apt to cause more harm than good. The public, meanwhile, was largely uninformed of how to respond and what steps to take to keep themselves safe. At about 8:55pm, the warning system would get one of its first major tests. While the earlier tornadoes had gone unwarned and largely unanticipated, the Cleveland office of the U.S. Weather Bureau was ready by the time a towering supercell crossed from Huron into west-central Lorain County, Ohio. Though the media infrastructure was far from ideal at the time, the warnings were quickly, calmly and accurately disseminated through television – where the announcements interrupted the new episode of I Love Lucy – and on the radio, as well as through local public officials: Cleveland was about to be in serious trouble. Unfortunately, while the message was widely heard throughout the city, widespread outages shortly afterward meant that many never received crucial follow-up information.

Around 9:00pm, a cone-shaped funnel dropped down from the darkening sky west of Kipton. Causing moderate damage to several homes, barns and chicken coops, the tornado traveled northeast through largely rural areas just south of Oberlin, Elyria and North Ridgeville.[9] Shortly before 9:45pm, the ragged funnel broke over the western horizon in Cuyahoga County and churned through a field near the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory on the northwest edge of Cleveland Hopkins International Airport. The tornado made close passes to a number of barographs and anemometers at the laboratory and the airport, causing some damage but providing scientists with a range of useful data about various aspects of the storm. The data indicated a core flow region between 66 and 233 yards wide,[10] and the damage was generally in the F2 range. One-inch hail and 60mph wind gusts were also recorded on both sides of the path. Damage in the F1 and F2 range continued on the outskirts of the city in a narrow path, with many homes suffering roof damage and some trees losing their tops or being uprooted.

The tornado intensified and grew in size as it crossed West 150th Street and marched on toward the center of the city, following half a mile south and roughly parallel to Lorain Avenue. Near the intersection of West 117th & Wayland, 44-year-old Louis Balint had just finished playing at the park with his twins, Gerald and Geraldine. Returning home to find the television on the fritz, Louis and his wife Mary put their children to bed, including three-year-old Pamela, and three-month-old Danny, whom they put in his crib in their bedroom. When the light rain that had been falling for some time gave way to hard, wind-driven torrents, Louis began to assemble the family in the living room. He ran to retrieve little Danny as the cacophonous sound of violent wind grew to deafening levels. The city may have had nearly an hour’s warning, but for Louis there was no time. The windows shattered as he reached his son’s crib, followed quickly by the roof and walls. He blacked out. When he awoke in the hospital, he was told that his wife, twins and daughter Pamela survived with minor injuries. His baby son Danny, however, would later be found five houses down the block, crushed beneath a heap of debris.

Several prefab homes, probably of poor construction, were apparently swept away on the west side of Cleveland.

Just south on Brooklawn Avenue, a group of five prefab houses and four others in construction were reportedly “cleaned off their foundations,” with nothing left but concrete slabs and gushing water pipes. This could potentially indicate F4 intensity depending on the details of construction.[11] Heavy damage was done to several dozen other homes between West 117th and Clark Avenue, and a number of schools and other brick and concrete buildings were also damaged. Seventy-year-old Mary Thom was killed on Elton Avenue when a section of her home collapsed on her. Two couples and a small child were killed when a group of brick homes near Franklin Circle were leveled. The nearby Detroit-Superior Bridge suffered moderate damage, and the tornado missed a street fair attended by nearly 1,500 people in this area by about two blocks. A truck servicing station at East 18th & St. Clair was partially collapsed, and a 10,000-pound semi-trailer was thrown into the side of a building down the street. The tornado damaged several other homes and businesses before drifting northeast over Lake Erie near Marquette Street. Though the tornado left eight people dead and at least 500 injured, it undoubtedly could have been much worse. Its track took it through some of the most densely populated portions of Cleveland, including downtown, but it remained weak (F1-F2) and relatively narrow through much of its “skipping” path through the city. A violent tornado taking a similar path could almost certainly have resulted in a tragedy exceeding even the Beecher disaster in scale.

Around the same time, the Beecher supercell spawned the final tornado of the night in central Lapeer County, Michigan. Beginning about two miles east-southeast of the Beecher tornado’s endpoint, damage began almost immediately as the home of 70-year-old George Benson was flattened along Lake Pleasant Road. Tracking over rural farmland, the tornado knocked down about a dozen barns and damaged a handful of homes between Rose Lake and Clear Lake. One home near Brown City Road was completely destroyed in F4 fashion and the homeowner was injured. The night’s final fatality came at the St. Clair County line along Abbott Road, where Loren Irish’s home erupted in a hail of debris and several family members were thrown into a field. Loren was killed and four others were seriously injured. The tornado continued to widen to a maximum of more than 500 yards, causing significant vegetation damage and blowing away several barns. At least a dozen more residents were injured as the tornado tracked a further 25 miles through northern St. Clair County, narrowly missing the small community of Yale and eventually passing the coast and dissipating somewhere over the waters of Lake Huron. With that, a devastating day of tornadoes had come to an end. One hundred forty-three people were dead and well over a thousand were injured, and yet the storm system responsible for the destructive outbreak was not through. All the conditions were coming together for one more deadly strike, and it would come in the most unexpected of places.

• • •

Residents across the country woke up on Tuesday, June 9, to sensational newspaper headlines and television reports detailing the disaster in the Great Lakes. Pictures of the funnels and the damage they wrought flashed on nearly every station and on every front page. The radio crackled with reports of massive damage, of triple-digit dead and of neighborhoods “wiped off the map.” Even at that early point it was clear that the tornado outbreak was one of the worst disasters in recent memory, perhaps surpassing the Waco tornado just a month earlier. For folks in Massachusetts, it all seemed a long way off; it was a tragic event, to be sure, but of course Nebraska, Ohio, Michigan and other such places were struck by tornadoes. They were tornado-prone areas, after all. Massachusetts, on the other hand, was not.[12] It was a sentiment shared even by many seasoned meteorologists at the time.

The U.S. Weather Bureau surface map from 1:30pm shows the low-pressure system progressing toward the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Around 10:00am, lead forecaster Al Flahive and other key staff at the Boston office of the U.S. Weather Bureau met at Logan Airport to discuss the day’s weather. The sweat rings and blotches adorning most of the forecasters’ shirts made one thing immediately clear — it was hot. In fact, it wasn’t just hot; it was the kind of aggressive heat that seemed to have its own weight, as if the sweltering atmosphere had momentarily transmuted into a vast hot tub on the highest setting. Clothing stuck to skin like cling wrap, sweat-soaked hair matted to heads and even breathing became a chore. The storm system that sparked the tornado outbreaks in the Midwest on the preceding days had continued its northeastward progression, tracking through southern Ontario and south-central Quebec and pulling vast quantities of high-octane tropical air into the warm sector — a small, wedge-shaped airmass squeezed between a cold front in western Vermont and east-central New York and a warm front sagging south near the Maine/New Hampshire border and through the eastern half of Massachusetts.

A hand-analyzed surface map from around 3:00pm shows the synoptic setup shortly before the tornado touched down, with the warm front extending roughly parallel and just northeast of the eventual path.

The upper-air dynamics also drifted along with the low pressure system. The elevated mixed layer, so important in aiding the violent outbreak the day before, had advected all the way through southern New England and come to rest above a very warm, humid near-surface airmass. It would again prove to be a key factor in the unfolding setup, increasing the volatility of the already unstable atmosphere. Along with substantial instability, the same rolling, twisting shear that had set destructive supercells in motion on the previous days was also sliding into place. Strong northwest flow in the mid-levels of the atmosphere pushed in atop southerly and even southeasterly winds near the surface, providing ample shear and helicity for any storm that developed. These atmospheric conditions – particularly the rare presence of an EML plume ejected from the Southwest – have since come to be recognized as strong indicators of the potential for significant severe weather in the Northeast.[13][14]

NOAA’s HYSPLIT model shows the source of two important airmasses over Worcester on the afternoon of June 9. The blue path shows the air at 700mb originating over Arizona’s arid Colorado Plateau, creating an EML. The red path shows a deep pool of warm, moist air near the surface originating over the warm waters just off the east coast.

The skilled forecasters at the Boston Weather Bureau recognized that a severe weather threat was taking shape. Strong thunderstorms seemed almost certain. Even severe thunderstorms and supercells seemed possible, and pattern recognition suggested that a tornado or two could not be ruled out. What was much less clear for Flahive and his staff was how to handle this information. There had never been mention of the word “tornado” in a forecast in the northeast. In fact, the Boston weather office had never even issued an advisory including the phrase “severe storms.” Official government policy had dictated for decades that the word “tornado” not be used in public statements, even when the risk was quite clear, for fear of causing a panic that could cause more harm than a tornado itself. Many within the bureau still held this opinion, and an internal struggle quickly developed at Logan Airport. It had become clear that a potentially dangerous day of severe weather was unfolding, but the staff were deeply concerned about causing unnecessary alarm for an event which seemed so unlikely. A compromise was reached at 11:30am. The Boston office released an unprecedented advisory warning of “..thunderstorms, some locally severe, developing this afternoon..” for Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island. There was, however, no mention of the word “tornado.”

• • •

Straddling the border of Worcester, Hampshire and Franklin Counties in central Massachusetts, Quabbin Reservoir sprawled north-to-south in a broken, irregular shape. Officials had only recently permitted motorboats on the reservoir, and by midday a number of boats plied the shallow, choppy waters. Fishermen drifted slowly across the broad expanse of water, trolling for a late-spring trout or working the shallows and lily pads for bass and pickerel. A stiff southerly wind dappled the water’s surface with flecks of white, bringing with it still more unwanted heat and humidity. Layered clouds and occasionally heavy rain showers meant good fishing conditions, but the clouds eventually gave way to nearly unbroken sunshine. About 100 miles to the northwest near Mechanicsville, New York, a field of cottony cumulus clouds had begun to grow, quickly climbing into the sky like slowly mushrooming atomic blasts. By 3:00pm, the puffy cumulus had transformed into a powerful supercell, the menacing thunderheads towering more than 40,000 feet into the sky. Drifting southeastward, the storm pounded the verdant hills of southwestern Vermont with torrential rain, golfball-sized hail and gusty winds. The skies crackled and boomed with tremendous electrical activity. And still, the storm continued to grow.

As the supercell crossed the Massachusetts border into Franklin County, the small town of Colrain was assaulted by hail as large as three inches in diameter and winds strong enough to uproot trees and snap large branches. The storm blew through the towns of Gill, Millers Falls, Farley and Erving with great force around 4:15pm, and baseball-sized hail crashed to earth like pearly white meteors south of Northfield. At the rear of the storm, a ragged wall cloud extended toward the ground behind a broad, flat, leaden base. Many of the fishermen on the Quabbin Reservoir began to take notice of the strange boiling and twisting motion of the massive cloud formation as it blew in from the northwest, and the residents of Petersham, about seven miles to the east-southeast, heard the crash and rumble of thunder growing in the distance. The low, rotating wall cloud began to spin faster as it narrowed and reached toward the earth. As the fishermen looked on, a funnel resembling “an enormous, tapered finger” descended into the thick forest just northeast of New Salem. Reports indicate the tornado displayed multiple vortices soon after forming, with some witnesses spotting three distinct funnels tearing through the countryside near the northern fringe of Quabbin.

As residents of Petersham looked on with equal parts fascination and horror at the swirling black mass, the storm passed just south of town with a “double-funnel” structure. Farmer George Jones, living just off Hardwick Road to the west of Petersham, was among the first to witness the swirling funnel in full. Staring out the kitchen window of the home he’d purchased and moved into just eight days ago, he watched as stands of trees snapped, uprooted and accelerated up into the maelström, flying like darts in the powerful wind. After sprinting to the cellar with his wife, he emerged to find part of his roof, attic and second-story walls gone, and a bare slab of concrete where his large barn had been moments earlier.[15] Several other homes along Hardwick Road and South Street were also damaged, and trees were snapped or uprooted in a quarter-mile wide path. Crossing South St. a second time as the road curved back to the northeast, the tornado pushed on nearly parallel to Route 122 before slamming into Connor Pond. The small pond, created by a dam on the eastern branch of the Swift River, was highly regarded throughout the area for its stunning natural beauty. The swirling funnel struck with full force, stripping and twisting trees and “sucking” some volume of water from the pond. A small island near the center of the pond was said to be torn up so thoroughly that its “esthetic appeal was destroyed forever.”[16]

After leaving a “skipping” path for a few miles, the twister continued with renewed fury.[17] Near the intersection of Old Stage Road and Allen Hill Road, a stately two-story farmhouse was collapsed by the force of the wind, portions of it swept into the forest downstream. Eighteen-year-old Beverly Strong, whose family owned the home, was thrown 300 feet to her death. Eleven-year-old Eddie White was also thrown from the house and killed, bits of his clothing becoming snagged in the treetops as he hurtled past. Eddie’s mother suffered a fractured back and other critical injuries when she was buried under the collapsing house, and his older sister, June, was reported to have been uninjured after she allegedly “floated” safely back to earth on a flying door. Continuing roughly southeast, the tornado missed downtown Barre and caused relatively little damage. In the tiny hill town of Rutland eight miles to the southeast, resident Rita Canney strained her eyes to make sense of the puzzling cloud formation approaching in the distance. She’d come outside after she was alerted by large hail pummeling her roof, but the strange, ragged cloud churning through a field just off Rutland’s Main Street had quickly diverted her attention. Rushing inside to grab a camera, Rita unwittingly snapped the first two photographs ever taken of a tornado in the northeast. About a mile to the south at the VA Hospital, a young staffer clearly noted the multivortex behavior of the tornado. “Suddenly the clouds lifted in the west, and it became quite light. Then a huge black cloud – like smoke – came directly out of the northwest, boiling furiously. I could see little wisps of cloud being whipped away from the big cloud, which was shaped like a cone.”[18]

The first known photograph of a tornado in New England, taken by Rita Canney as the tornado tore through a field just outside of Rutland.

Near the intersection of Main Street and Edison Avenue, elementary school principal Donald Marsh and his family had just sat down for dinner when the tornado struck. The house was splintered and collapsed on the family, throwing Donald into the yard along with his daughter, Linda. Donald was killed instantly, and his wife Margaret suffered a fractured spine when she was trapped under debris. Five-year-old Linda was thrown into a tree in the yard, where she was impaled against the stub of a broken tree limb but miraculously survived. Two-year-old Dwight was found, alive and virtually unharmed, underneath his father’s lifeless body. Whether Dwight’s survival was pure fortune or an act of sacrifice on the part of his father isn’t clear. The town’s second fatality came just a few doors down Edison Ave, where the new home of Margaret Harding and her 16-year-old son Robert was completely obliterated and swept cleanly from its foundation. Robert was killed when he was thrown into a nearby field. Further up Main Street, the home of Maurice and Peggy Gordon was reduced to a pile of rubble. Seeking shelter in their basement, the couple were trapped beneath the heavy timbers and other debris. After finally freeing themselves, they emerged to find their brand new 1953 Chevy Bel Air blown a hundred yards and heavily damaged. At another home that was swept away, a heavy set of poured concrete steps was blown ten feet from the former site of the house. After spending the first 20 miles of its lifespan terrorizing sparsely populated farmland and small hill towns, the Worcester tornado was about to encounter heavily populated areas for the first time — with predictably tragic results.

Maurice Gordon’s Chevy Bel Air was blown 100 yards from his home, the ruins of which can be seen in the background.

• • •

Stanley Smith snapped this photo of the tornado as it passed just southwest of downtown Holden, shortly before devastating the Winthrop Oaks and Brentwood subdivisions.

At first, the town of Holden seemed to have dodged a bullet. Traveling half a mile south and roughly parallel to Route 122, the tornado expended its energy in the heavily forested hills and valleys to the southwest of Main Street. Several homes were impacted, but little significant damage was recorded. That all changed just minutes after 5:00pm, as the tornado cut a diagonal path across Salisbury Street and blasted through the home of 37-year-old Arne Hakala. Arne and his six-year-old daughter Liisa were thrown from their disintegrating home and killed instantly, while Arne’s wife and ten-year-old son were severely injured. Moments later and a quarter mile to the south, William Martilla’s home was also demolished and swept away. William and his son survived, but his wife Virginia was thrown into the woods across the street and killed. Crossing the shallow Chaffin Pond, the growing funnel enveloped the west side of Main Street just south of Alpha Road. Twenty-eight-year-old Ruth Oslund was preparing supper when she heard the monstrous roar approaching from her west. Grabbing her two-week-old son Charles, Jr. in a panic, she bolted from her cottage and broke into a dead sprint, desperately seeking more substantial shelter. The tornado overtook her in seconds, sending mother and son hurtling 150 yards through the air. As they impacted the ground a blinding pain caused Ruth to release her grip on her infant son, who was snatched away and sucked into the debris-choked maelström. His body was found three days later, buried under a heap of debris, more than 500 yards from the bare foundation of his family home.

A number of homes in Winthrop Oaks were completely flattened. In this aerial view, the black X marks the spot where little Charles Oslund, Jr. was found, 500 yards from his mother’s home.

Within seconds, the tornado crossed Main Street and swallowed up the newly built Winthrop Oaks subdivision. A private development consisting of 75 Cape Cod-style homes, Winthrop was devastated by the multivortex monster. All but 12 of the homes suffered damage, and about two dozen were completely wiped away and scattered for hundreds of yards in a fairly narrow swath that may have been caused by a subvortex. The home of Charles McNutt, at the southeastern end of Winthrop Oaks, was completely destroyed and “smashed into matchsticks,” and trees in this area were stripped bare of bark and limbs. About half a mile away in the Brentwood development, baseball-sized hail had been pounding on roofs and shattering the windows of any cars unfortunate enough to be parked outside. Children across the neighborhood went sprinting outside to pluck the largest stones, stowing them away in their freezers for future proof of the odd occurrence. On Brentwood Drive, 12-year-old Laurence “Larry” Faucher struggled against the biting wind to push his bicycle back to his home a few doors down. Charles and Alvera Faucher, Larry’s aunt and uncle, watched from their kitchen window and mused at the oddity of the whole scene. Suddenly, the Fauchers noted shingles and other bits of debris being torn from their roof and zipping away in the growling wind. A hundred yards to the west on Fairchild Drive, Edward and Florence Butler had just left their driveway in their Buick and were passing the home of 59-year-old Alice Beek when the tornado struck.

The destruction was swift and utterly complete. The Butlers’ Buick was thrown from the road, landing upside-down in Charles Faucher’s lawn. Edward was crushed to death upon impact. His wife was ejected from the vehicle and hurled to the south, where she landed in the basement of the disintegrating home of Jack Fairchild, the developer responsible for building the Brentwood subdivision. Alice Beek’s home was torn apart by the savage winds, throwing Alice into her backyard with her right leg nearly torn off by a debris strike. Her femoral artery severed, Alice died within moments. One hundred and fifty yards to the south, Sidney and Elsie Regan were quickly buried beneath the mountains of rubble that had moments earlier been their and their neighbors’ homes. Sidney survived his injuries, but Elsie died from blood loss on the way to the hospital. Near the corner of Brentwood Drive, the Faucher home was pulverized just as the family scrambled for shelter in the basement. Mr. and Mrs. Faucher and their young daughter were badly injured but eventually recovered. Little Larry Faucher, however, never made it to his home. He was swept up when the tornado struck and thrown some distance, coming to rest in a field with his bike nowhere in sight. As the twister finally ground past, the scene was striking in its solitude. Brentwood was gone. Rows of attractive suburban homes had been transformed into an alternating checkerboard of clean foundations and shattered rubble piles, the tree-lined streets instead flanked by ghostly white nubs.

• • •

A few minutes after 5:00pm, the rapidly expanding tornado barrelled into the northwest side of Worcester. Dozens of upscale homes along Brattle Street were damaged or destroyed, some of them smashed to bits. Just to the east on Chevy Chase Road, the home of Arthur and Virginia Harrison stood as one of the most attractive in the city. The expensive, well-built home had been featured in a recent issue of Better Homes and Gardens, and was a source of great pride for the Harrison family. The tornado decimated the home and swept it away in a matter of seconds, killing Mrs. Harrison on the spot. Next in its path was the Norton Company, the world’s largest manufacturer of abrasives and grinding wheels and Worcester’s single largest employer. The sprawling complex occupied nearly a mile of real estate between Ararat Street and West Boylston Street, including dozens of shops and facilities that employed more than 5,700 local workers. Fortunately, the complex suffered only moderate damage. The roof was torn off the main building and virtually every window in the complex was shattered, but the employees inside survived with only a handful of injuries. In the parking lot outside and in several of the surrounding streets, vehicles were thrown, rolled and some reportedly “sandblasted” by the intense wind. Clothing, scraps of paper and other debris from Holden and other points upstream rained down before, during and after the storm’s passage. Just over a mile to the south, Howard Smith, award-winning photographer for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette, stood on the eastern shore of Indian Lake. He’d been on assignment when he noticed a vaporous, undulating cone blotting out the northwestern horizon. Acting quickly, he turned his camera to the north and snapped one of the most enduring images of the event.

Howard Smith took this photo facing north from the eastern shore of Indian Lake. The tornado was rapidly gaining in size and intensity at this time, cresting the hills on the city’s northwest fringe before bearing down on the homes along Brattle Street.

At Fortin’s Market, a supermarket on West Boylston Street in the Greendale neighborhood, sisters Ann Lovell and Joan Karras had just finished their shopping when the weather outside began to deteriorate. The midday sun had been choked out by thick, billowing clouds. The needling rain came in bursts, swirling in little eddies as the blustery wind whistled through the streets and corridors. As the sisters headed for the door to make the drive home with Joan’s husband, the shop’s proprietor, Simeon Fortin, urged them to stay through the storm. They declined, worried that their mother would be concerned if they didn’t return when they were expected. They’d been gone for just moments when the large storefront windows began to shatter. Fortin sprang into action, quickly guiding his employees and patrons toward the relative safety of the kitchen. Ann, Joan and her husband had no such safety to seek. They’d made it about a quarter of a mile north on West Boylston Street when the angry, billowing funnel approached from their west. Timber from the Diamond National lumber yard across the street began hurtling toward the car, easily penetrating through the windows and doors. The car was lifted from the road and thrown several hundred yards, finally coming to rest upside-down in the rubble of a house several streets down. As would be the case with victims throughout the path, the bodies of the sisters were so disfigured that it took some time to identify them. Joan’s husband, Peter Karras, was initially thought to be dead when his blood-soaked body was found. Miraculously, he clung tenaciously to life and eventually recovered.

Residents pick through a rubble pile, typical of those found in the Greendale area after the tornado.

To the east, a stretch of “three-deckers” – three-story homes typical of the Worcester area, with separate living spaces on each floor – were collapsed or blown apart by the storm. At 40 Randall Street, Bobby Frankian saw the tornado coming from his third story room and ran to alert his mother. The structure began to collapse like an accordion as mother and son ran to the second floor and huddled together for protection. It was over in moments, and the Frankians emerged to what looked like a warzone. Their thoughts quickly turned to the families on the first and second floors. Ten-year-old twins Donald and David Karagosian emerged from the rubble of the second floor without serious injury, having taken shelter under a sturdy table as the house began to collapse. Their mother, Anna, was found crushed between the collapsing second and third floors. On the first floor, the Aslanian family – Betty, daughters Nancy and Marilyn, and mother-in-law Mary – were buried beneath the remnants of the house. Rescuers were forced to dig a tunnel to access the family, where they found little Nancy crushed to death beneath a heavy radiator. Across the street at 43 Randall, 75-year-old Sigrid Johnson was also crushed to death on the first floor of a collapsed three-decker. Several others also met the same fate as three-deckers crumbled across the Greendale neighborhood. As if the tornado hadn’t been enough, fires broke out along Francis Street and quickly consumed a number of the homes that had survived the storm relatively unscathed.

Assumption College, then an all-male school founded and largely populated by French-Canadians, stood near the top of the broad, grassy slope of Burncoat Hill. As the violent wedge crossed West Boylston Street and approached the college, a large, steel-walled tank containing several thousand gallons of fuel smashed into the structure’s brick façade with tremendous force. The tank had been sucked up from a salvage yard several hundred yards away, and the impact tore a massive hole in the three-foot-thick walls. Other sections of wall quickly followed, blowing in and collapsing the heavy floors above. Father Englebert Devincq, a professor at the college, was buried under several feet of brick and granite when the floors above him collapsed, causing his second-floor room to give way and sending him crashing into the first floor. Rescuers worked feverishly to extricate him, but he passed away before he could be pulled from the rubble. A wooden convent near the main building, home to the sisters who staffed the college’s kitchens, was picked up virtually whole and dashed to the ground, sending the women inside scattering into the churning debris field. Twenty-seven-year-old Jacqueline Martel and 48-year-old Marie Alice Simard, known respectively as Sister St. John of God and Sister Mary St. Helen, were killed instantly. Several other sisters sustained injuries, many of them critical, but all survived.

An aerial view of the damage at Assumption College. In the bottom right corner are the remains of the convent where two nuns were killed.

• • •

The Worcester tornado was nearing peak intensity as it thundered across Burncoat Hill and toward Clark Street. Just off the main thoroughfare, rows of brand new Cape Cod and Ranch-style homes lined then-unpaved Uncatena Avenue. The tight-knit neighborhood was populated mainly by 20- and 30-somethings, most of them with two or three children. The multivortex monster struck with extraordinary fury, carving a swath nearly a mile wide.[19] Violent subvortices raked Uncatena Avenue, completely obliterating and sweeping away dozens of homes. Cars were blasted by the wind and thrown hundreds of yards, and trees were stripped down to stubs. At 146 Uncatena, 15-year-old George Steele had gone across the street to visit his best friend, Mike Sullivan. The boys were thrown from the attic of Mike’s home as it disintegrated around them. Their bodies were later found together several hundred yards away amid the scattered debris. Next door, nine-year-old Beverly Clement was killed when her home was swept cleanly away. She was thrown down onto the bare slab, her skull crushed by the impact of a hot water tank. Thirty-two-year-old William Heyde was killed about half a mile to the north when he was struck in the head by an airborne object. Even among those who survived, the injuries were gruesome. There were several amputations and compound fractures, and many victims and survivors had been “sandblasted” by grit picked up from the unpaved road, bits of glass from shattered windows and other fine bits of debris.

The tornado reached peak intensity at Uncatena Avenue, where every home in the center of the path was obliterated and swept cleanly away.

At 130 Tacoma Street, Paul Pederson had just woken up from a nap. He’d worked earlier in the day and had volunteered to come home and babysit his baby daughter, Valerie, while his wife Mary took their daughter Mera and son Paul shopping. The following day was Mera’s fifth birthday, and Mary was eager to make sure the party would be a memorable one. As Paul sat down to read the evening paper – headlined by the disasters in Beecher and Cleveland – his wife and children had finished their shopping and boarded the Lincoln Street – Great Brook Valley bus for the short ride home. Outside his bedroom window, Paul heard a “whirling, screaming noise.” Taking a quick glance, he could see the caliginous mass on the northeastern horizon. With no time to reach the basement, Paul ducked into the relative safety of the first-floor closet, kneeling over his young daughter Valerie. Riding out the calamitous storm as their home suffered heavy damage, father and daughter emerged unharmed. At about the same time and just to the south, Mary Pederson’s bus was engulfed by the whirlwind as it neared the end of its route. Implored by the bus driver to hit the floor, Mary positioned her children in the aisle and threw herself over them. The 12-ton bus rocked and shifted, slowly at first, before becoming airborne and tumbling like a matchbox toy in the teeth of the howling wind. The stanchions lining the aisles were torn loose, one of them impacting Mary and virtually decapitating her as she was thrown into the air. Ten-year-old Larry Demarco was also killed when the bus finally came to rest, smashing into the side of one of the nearby apartments at the Curtis Apartments complex.

The city bus in which Mary Pederson was killed. Behind the bus is the hole made when the bus was thrown into one of the Curtis Apartment buildings.

Just to the west of the Curtis Apartment complex, the unpaved Chino, Yukon and Humes Avenues ran parallel to Tacoma Street. An attractive, quiet neighborhood had been built up over several decades, consisting of single-family homes on large, well-manicured lots carved into the rolling patch of land. The tornado blew through in seconds, leaving a scene mirroring that of Uncatena Avenue; homes on all sides were completely torn apart and swept cleanly away, leaving only concrete slabs arranged, quite appropriately, like rows of oversized grave markers. At 44 Yukon Avenue, 58-year-old Joseph Falcone had just arrived home from work. As always, his wife appeared on the porch to greet him. Apparently unaware of the approaching threat, husband and wife were thrown from their home as it was swept away. Their bodies were found in a nearby field still locked in an embrace, together in death as they were in life. Their neighbors, 63-year-old Frank Dagostino and his wife Catherine, suffered the same fate. Panicking as their home was torn apart around them, the couple ran into the street in a desperate search for shelter. Almost immediately, both were struck down by the swirling cloud of high-speed debris. Frank was killed instantly by several blows to the head, while Catherine would succumb the following evening at a nearby hospital. Fifty-nine-year-old Victor Marcinkus and his wife Katherine were crushed when their home at 25 Yukon Ave. was razed. Also strewn among the rubble were Oscar Skog, May Slack, Abbie Gleason, Annie Hutton and her six-year-old granddaughter Barbara.

Complete devastation to the west of Curtis Apartments. The view is facing south and the streets pictured, from left to right, are Tacoma, Humes and Yukon.

William Riley, a Pittsburgh resident visiting friends in the city, was driving north on Great Brook Valley Parkway with his ten-year-old daughter Sheila when a large tree was thrown onto their car. Thomas was found minutes later, crushed to death inside the car. William’s wife Mary, whom he’d just dropped off at Great Brook Valley, began a frantic search for her daughter after learning of her husband’s death. At City Hospital, she found a heavily bandaged, badly injured ten-year-old girl who appeared to be wearing little Sheila’s ring. Believing that she’d found her daughter alive, Mary was crushed to learn that the young girl was actually Martha St. Germain, as confirmed by the girl’s mother when she arrived. It would be hours before Mary learned that Sheila was found in the family car, her body so badly mangled that rescuers initially missed it when extricating her husband. Across Route 70 just southeast of Great Brook Valley stood Brookside, also known as the Home Farm. Built in the 1930s as a New Deal project, the farm housed about 250 derelict, elderly or infirm residents who also tended to the large herd of dairy cows on the grounds. The barracks, the farm facilities and most other structures were flattened, and nearly two dozen men plummeted 18 feet into the dormitory basement when a stairwell collapsed. Six people were killed when they were buried in the wreckage. Many of the nearly 100 dairy cows were also killed, some of them thrown and scattered for hundreds of yards in all directions.

• • •

Snaking along the west side of Shrewsbury and up to the southern border of Worcester, the long, trench-like Lake Quinsigamond was speckled with debris of all sizes and shapes. Dead cows bobbed in the water or washed to the shore. Pieces of roofs and siding and other objects splashed down in advance of the grimy funnel. Roaring across the northern edge of the lake, the tornado obliterated several structures on the northeast shore. Among them was the home of Lawrence and Nora Daly, who were thrown along with their pulverized home into the lake. Like the Falcones several miles to the northwest, husband and wife were later found along the lake, locked in a final embrace. Half a mile to the east, three high-voltage transmission towers were toppled and destroyed. These towers would later be used by engineers including C. A. Booker, an employee of the New England Power Service Company, in an effort to estimate the tornado’s wind speed.[20] Using their knowledge of the expected failure point of the towers in question, as well as the contemporary understanding of the physics of tornadoes, the engineers estimated a peak wind speed of 343mph near the tornado’s center. This estimate was widely accepted at the time, but we now know that the engineers did not account for, nor understand, the tornado’s complex multivortex structure. The study also did not consider debris impacts and other factors which can cause damage well beyond what would be expected for a given wind speed.

This photo was taken by Henry LaPrade, facing north-northwest from 53 Wells Street as the tornado roared across the northern edge of Lake Quinsingamond.

On the vast, sprawling grounds of the Brewer Estate, laid out along Maple Avenue, the Italian-inspired mansion was joined by a number of small cottages. The mansion escaped with little damage, but the cottages were razed. Two of the occupants, Ethel McDonald and Catherine O’Hearn, were killed. At 335 South Street, the large duplex shared by the Sanborn and Fisher families was leveled. Three-month-old Marlene Fisher was buried under debris and died within minutes. On the southern side of Shrewsbury, 80-year-old Thomas Howe was driving south on Route 20 with his wife, Cecilia, and his middle-aged daughters, Ruth Carlson and Harriet Loving. The tornado hit their vehicle like the shockwave of an atomic bomb, throwing it off the road and tumbling it a hundred yards into a shallow gulley. Forty-five-year-old Harriet was the only survivor. Shortly after blowing through Shrewsbury, the tornado began a long, arcing turn toward the east-northeast. After cresting a low, wooded rise called Whitney Hill, the tornado roared into the west side of the community of Westborough. At the farm of prominent cattle dealer Charles Aronson, he, his wife and his 14-year-old daughter Sheila saw the broad, dark wedge approaching. Neighbors recounted witnessing the family run from their home, only to scurry back in as the tornado approached. Their large home was destroyed, killing all three. Several barns were destroyed as well, and a farmhand named Henry Bailey was killed when he was struck down by a heavy wagon that had been thrown several hundred yards. The tornado continued its gradual turn, tracking east-southeast before sharply shifting northeast on the southeast side of town. Several dozen homes suffered damage on the southern fringe of Westborough, ranging from removed roofs to complete destruction. On Flanders Road, just northeast of Cedar Swamp Pond, Harriette Cahill was killed when she was thrown from her home.

This photo was taken by Robert Resch from the intersection of Routes 9 and 20 on the southwest edge of Shrewsbury. The tornado had just passed through town, causing massive damage.

Robert Resch’s second photo, taken from near the Southwest Cutoff on Route 20, shows the tornado passing close by to the south.

The vast funnel began to slowly shrink as it approached Route 9 at an oblique angle. Crossing several rural roads just to the south of the turnpike, the twister destroyed about a dozen poorly built homes and injured at least two people. Two others, a mother and son, were injured when they were pulled from their rolling vehicle on the turnpike. The Davco Farm, on Breakneck Hill Road, was completely destroyed and livestock was thrown about and killed. In the small community of Fayville, just to the northeast on the north side of Route 9, the local post office was among the last buildings destroyed by the tornado. The final fatalities would be pulled from the rubble here – 26-year-old Irngard Noberini, her one-year-old son Robert, and the wife of postmaster James Trioli. Finally, after scouring the earth for 47 miles over 84 minutes, the Worcester tornado unceremoniously dissipated over the southern end of the Sudbury Reservoir. In its wake, eight communities laid broken and 94 people were dead. So great was the ferocity and scale of the damage that many residents initially believed the Soviet Union had launched a nuclear attack on the sleepy Massachusetts countryside. In the words of one survivor, “perfectly sane adults were running around saying the Russians had attacked, or that this was the end of the world.” A wedding dress from the north side of Worcester was found the following day dangling from a power line in Natick, 20 miles away. Tar paper, clothing, insulation and other debris was transported even further eastward, landing at Blue Hill Observatory and raining down across the Boston suburbs. A chunk of frozen mattress was later found bobbing among the waves on the eastern end of Massachusetts Bay, more than 50 miles away. A scrap of paper originating in Holden was found in Cape Cod the following day, more than 100 miles to the southeast.

As the Worcester tornado dissipated, another tornado descended from the skies just southwest of Millbury. After destroying a home near Pleasant Valley, the tornado obliterated the Brigham family home on the eastern fringe of Sutton, near the border with Northbridge. The Calmer and Dakin farms were destroyed just to the south, and more than 1,500 chickens “disappeared” when several large poultry houses were swept away. Chicken carcasses, stripped of feathers, reportedly rained from the skies over Foxboro about 25 miles to the southeast. Two of the heavy brick walls were torn from the Kupfer Brothers factory in Northbridge, and a number of homes suffered moderate damage. Trees along the path were uprooted or snapped, and several farms were destroyed. After dissipating near Mendon, a second tornado touched down several miles to the east of Bellingham. After causing moderate damage to several homes near Franklin, 17 people were injured near Wrentham when a number of vehicles were thrown from a highway just outside of town. The tornado continued for just under ten miles before roping out north of Mansfield. Fifteen homes and a large Country Club lodge were damaged or destroyed by a brief tornado on the south side of Exeter, New Hampshire, which occurred while the Worcester tornado was in progress.

• • •